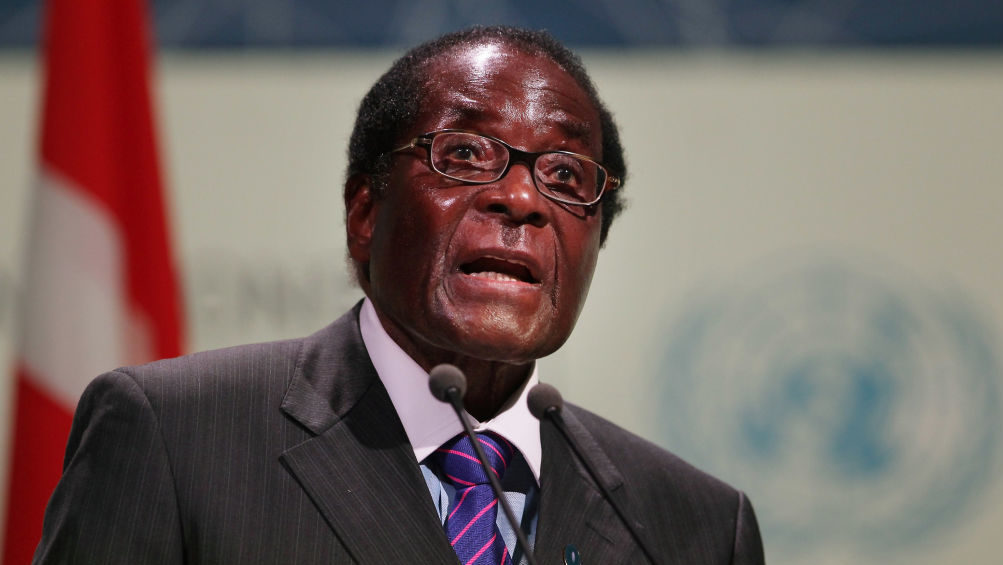

OPINION: Liberation, violence and the complex legacy of Robert Mugabe

Journalist and adjunct professor Milton Allimadi explores the complex legacy of Robert Mugabe and what it means for African liberation.

The death of 95-year-old former president Robert Mugabe has taken me down memory lane.

I remember running outside in celebration as an 18-year-old freshman at Syracuse University in 1980, waving a copy of The New York Times that carried the story of Zimbabwe’s independence.

READ MORE: Former Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe died in Singapore

African Liberation

Mugabe was one of the great heroes of African liberation alongside Kwame Nkrumah, Nelson Mandela, Julius Nyerere, Patrice Lumumba, Samora Machel, Amilcar Cabral and others. He was also one of the most intelligent and articulate leaders. His legacy will be a mixed one because he clung on too long to power.

When he escaped into exile he led his Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) party and its military arm. His counterpart in the struggle was Joshua Nkomo, who led Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu). The two teamed their forces to fight against the racist regime, under the banner The Patriotic Front.

Africans, including in Diaspora –African Americans, Caribbean, in Brazil, Europe and elsewhere– rooted for the Patriotic Front. Victory against Ian Smith’s White minority regime in Rhodesia was seen as one-step closer to the big prize; defeating apartheid in South Africa.

When Britain realized that Smith’s regime was about to be defeated, it organized independence talks at Lancaster House in the U.K. This paved the way to elections won by Mugabe in 1980.

READ MORE: Black votes will define 2020 presidential electability for Democrats

Violence and Sanctions

Mugabe invited his sometimes-rival Nkomo into his cabinet. After a falling out between the two, Mugabe unleashed the army on Nkomo’s stronghold of Matabeleland region, ostensibly to quell rebellion. Between 1983 and 1987, thousands of civilians —some reports say tens of thousands— were massacred. This episode tarnished Mugabe’s reputation to many Pan-Africans.

During the Lancaster House negotiations Britain had pledged funding to help the post-independence government buy the land from White farmers under a policy called willing-buyer, willing-seller. There were not many willing-sellers; Whites didn’t want to surrender their privilege. When a new government came into power in Britain in 1997 under Tony Blair, it ended financing of the purchase of land. Mugabe’s government said it couldn’t justify paying White settlers for land that their ancestors stole when the country was colonized in the 19th century. The government encouraged land seizures; they were often violent and some White farmers died.

Africans won back their land. This is a feat not yet accomplished even in South Africa where, 25 years after the end of apartheid, whites, who make up less than 10% of the population own 72% of private farmland.

A Complicated Reputation

During one of his addresses to the United Nations General Assembly, Mugabe famously declared, “We are not Europeans, we have not asked for any inch of Europe; any square inch of that territory. So Blair, keep your England and let me keep my Zimbabwe…People must always come first in any process of sustainable development; and let our Africans come first in the development of Africa. Not as puppets, not as beggars, but as a sovereign people.”

These were the kind of declarations that won continued support for Mugabe in the global Pan-African community.

Mugabe was thoroughly demonized in Western media. When he was invited to City Hall in 2002 by City Council-member Charles Barron, scores of reporters came.

Mugabe offered a comprehensive historical account of how the land had been violently stolen by white settlers. In the end, having been schooled, not a single one of the reporters asked him a question.

Back home, the sanctions took a heavy toll and Mugabe was increasingly violent toward the opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai. The economic downslide created hyperinflation, destroying the national currency. By 2015, Zimbabwe had replaced its currency with the U.S. dollar.

An aged and frail Mugabe clung to power. His much younger and ambitious wife, Grace Mugabe, wanted to succeed him as president. There were rumors that she poisoned then Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa –he survived– to remove any obstacles. As a power struggle intensified between Ms. Mugabe’s supporters and Mnangagwa’s, the military sided with the Vice President and eased Mugabe out of power.

Mugabe had started out as a hero of African liberation and champion of Pan-Africanism. By wielding power for 37 years, many Zimbabweans who came of age at a later stage will associate the country’s economic demise as his legacy. But millions more will remember the return of the land to Africans.

Ironically his death may now pave the way for the lifting of Western sanctions, which is something Zimbabwe badly needs to restore it’s economy.

Milton Allimadi publishes Black Star News www.blackstarnews.com and is an adjunct professor of African History at John Jay College. He doesn’t believe in geographical boundaries and his motto is “One Africa, United.” He enjoys listening to Malcolm X’s ‘The Ballot or the Bullet Speech’ while doing sit-ups. Follow @allimadi on Twitter.