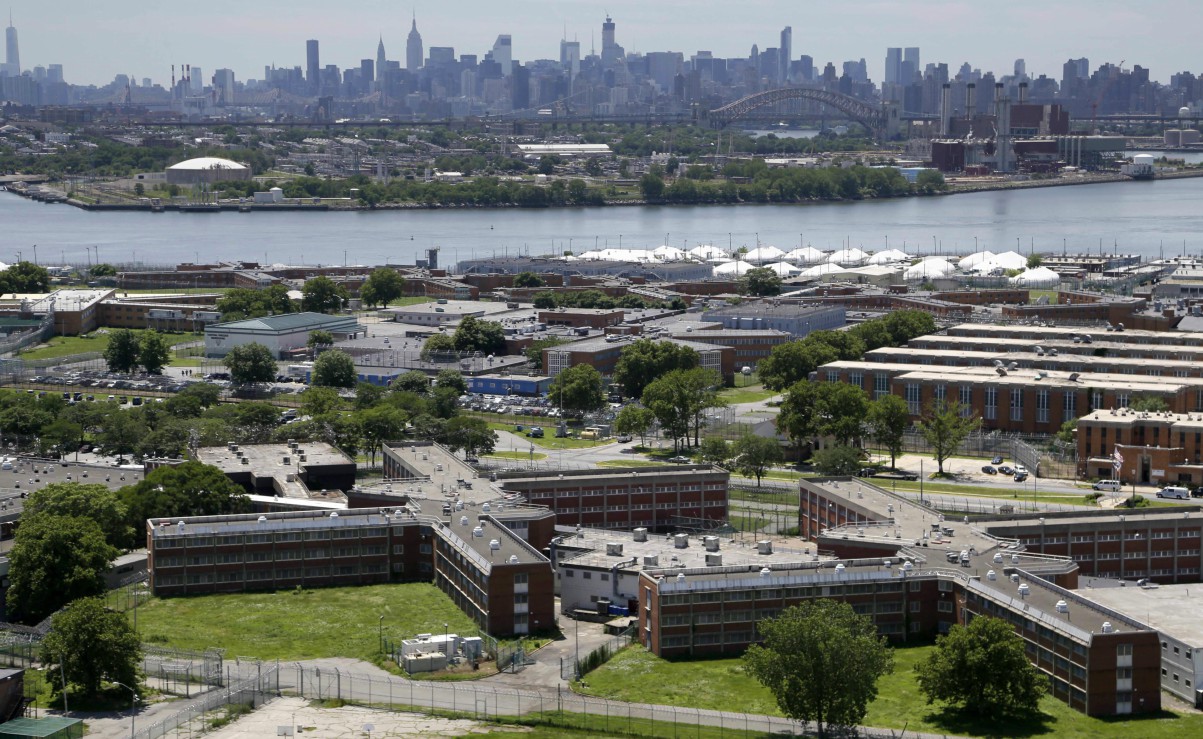

Coronavirus rips through notorious Rikers Island jail complex

theGrio investigates how the coronavirus pandemic has turned Rikers Island, one of the world’s most notorious penal complexes, into a petri dish.

On a good day at Rikers Island, toilets are clogged, soap is scarce and a giant rat might scurry across the day room, sending the most hardened inmate jumping.

But in the last several weeks, the coronavirus pandemic has turned one of the world’s most notorious penal complexes into a petri dish. Through their lawyer, inmates told theGrio that even though the city has freed hundreds of inmates in the wake of COVID-19, the New York City complex is still cramped and more unsanitary than usual.

Coughing is heard all around and one detainee who was recently released said it took weeks for him to receive clean sheets or towels and that he never received needed pain medication for an injury. Inmates see messages about social distancing on TV but must sleep two feet apart in dorms.

READ MORE: Atlanta woman’s death raises more questions about COVID-19 risk in prisons

While local and state officials are announcing flattening infection rates among the general public, the rates at Rikers remain high. Conditions at the complex have most likely helped push the COVID-19 infection rate at the New York City complex as of May 2 to a stunning 9.67 percent, almost five times the 2.04 percent infection rate of New York City and about 28 times the .35 percent infection rate of the United States, according to data provided by the non-profit Legal Aid Society.

According to the New York City Department of Correction, 370 New York City jail inmates, including those at Rikers, have COVID-19, three have died in the hospital, 1,148 DOC staff have tested positive and 174 state health staffers connected to Rikers have tested positive as of May 3.

Criminal justice advocates maintain inmates are not being given the tools they need to protect themselves. Detainees at Rikers are people who are awaiting trial, serving time for violating parole, or those serving shorter sentences. Fifty-three percent are Black.

“Regardless of whether someone has been convicted or is awaiting trial or is guilty or innocent, I think it’s a human right to be able to protect your health and to be able to stay safe during a deadly pandemic,” Kalle Condliffe, a defense lawyer with the society, told theGrio.

Legal Aid is part of a coalition of organizations that are pushing for the release of everyone in Rikers during the pandemic.

READ MORE: Meek Mill and Michael Rubin link with Madonna to send masks to prisons

“COVID-19 is spreading rapidly at Rikers Island and other local jails, endangering our clients, correction staff and all of New York City,” Tina Luongo, attorney-in-charge of the Criminal Defense Practice of the Legal Aid Society, said in a statement.

The Department of Correction declined to allow interviews with staffers on the island. The state Department of Health declined interviews too.

For its part, the city agency unveiled a COVID-19 response in March. It includes communicating changes at roll call, posting pandemic-related information around the island, posting health advice on television monitors, sending home staff members who appear sick, providing soap to inmates on request, and providing additional sanitation training to those in charge of keeping Rikers clean.

“This dramatic reduction in the detainee population is a significant development which has allowed us to increase social distancing within our facilities as we deploy all available measures to fight the COVID-19 virus,” Cynthia Brann, commissioner of the NYC Department of Correction, said in a statement. “We are doing all we can to ensure the health and well-being of everyone who works or lives in our jails.”

Throughout history, Rikers has held negative connotations for Black people. Richard Riker, a descendant of Dutch immigrant Abraham Rycken who once owned the island, was a judge known for his participation in an exclusive club that kidnapped Black teens and steered them into slavery. Solomon Northup, whose story was told in the book and movie “Twelve Years a Slave,” was a victim of this type of operation.

In modern times, the island between the Queens and the Bronx has been the poster child for jail reform advocates, particularly after the widely reported 2015 suicide of Kalief Browder. The young Bronx man maintained he was innocent of charges that he stole a backpack. Because he could not afford bail and his court dates kept getting postponed, he spent three years at Rikers, two in solitary confinement.

Under mounting pressure, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan in 2017 to close Rikers over 10 years and replace it with neighborhood facilities. The movement has gradually nudged the population down from 10,000 three years ago to 3,828 on May 2, according to the Legal Aid Society. That nudge down was partially helped along by New York State’s bail reform law that took effect Jan. 1. It bars criminal courts from setting cash bail for a majority of misdemeanors and violent felonies.

While city residents debated the wisdom of bail reform the coronavirus came seemingly out of nowhere. In late March, after the first Rikers inmate tested positive, New York City announced plans to release detainees serving sentences of less than a year for nonviolent misdemeanors. De Blasio said his administration also was working on a case-by-case basis with prosecutors to release older inmates with preexisting health conditions.

In the meantime, those who remain are forced to live in conditions that inmates say were challenging even before COVID-19.

“It was disgusting,” recalled Vidal Guzman, a former Rikers detainee who now works with the #CloseRikers campaign to shut down the complex.

“You might be eating and see a huge-ass rat just running through the day room,” he added. “There are rats, roaches, you might see a waterbug running through your cell. It’s beyond disgusting.”

Since the advent of the pandemic, cleaning supplies have not been upgraded, and the inmates represented by Condliffe, who agreed to share information with theGrio, said they’ve each been given only two masks to make do. They say only inmates with the harshest symptoms are sent to the infirmary, never to be seen again.

READ MORE: Dyjuan Tatro of ‘College Behind Bars’ talks education reform for prisons

With visits forbidden since March to keep COVID-19 at bay, about 30 inmates a day might use the same landline telephone to speak with loved ones and lawyers. Inmates are given supplies to clean the phones between uses, but there is no guarantee that everyone is doing this, the inmates said.

“Do you trust the last person who used the phone thoroughly cleaned it?” Condliffe asked. “That is a particular concern to me, and as grateful as I am to have connection with my clients, it also worries me every time that they call me because it means that they’re using a phone that’s being used every day by 30 other people.”

While the rest of the world is practicing social distancing, washing hands every 20 minutes and keeping surfaces clean, inmates at Rikers — isolated in the waters near New York’s LaGuardia Airport — are sleeping in packed dorms two feet from one another, listening to their fellow inmates cough and trying to preserve the slender, motel-style soap issued to them.

While most people have expanded their use of bleach and virus-grade disinfectant to keep their homes clean, Rikers detainees — responsible for upkeep — are cleaning the facility as best they can with the industrial-grade supplies they’ve always been given. One bottle of bleach is provided to clean a unit of 18-35 men, they said.

The situation has prompted the Legal Aid Society, a nonprofit that provides free legal representation to indigent defendants, to lodge multiple lawsuits against the Department of Correction. Conditions have been difficult for corrections officers and other staff too. A lawsuit filed by three unions representing corrections officers refers to New York City’s jails as “a cesspool of illness.”

“It is a miserable place – the atmosphere is frequently tense,” Condliffe told theGrio. “From what my clients tell me, now the atmosphere has gotten even more tense because people are even more than usual aggravated by their situation. I think the officers are also feeling stressed and scared.

Several inmates agreed to describe conditions to theGrio through Condliffe. Speaking anonymously, they described conditions that are markedly worse than what the city’s Department of Correction has been telling the press.

One client said he’s requested several times for a visit to the clinic in his building to no avail. He needs pain medication and no one is giving it to him. Normally, inmates are able to visit the clinic right away.

Also, complicating matters is that even though visits are canceled, for now, corrections officers, staff and inmates move frequently through the same places.

“My clients say, ‘We can’t social distance,’ “ Condliffe said. “You can’t keep away from people and it’s increasing the tension.”

The detainees have gotten the message about social distancing, but they are not able to practice it.

“It’s crazy making,” Condliffe said. “They are being given information that they should be socially distancing and they’re allowed to see the TV that says they should be socially distancing but then they can’t.”

She added, “There are people all over the place coughing and sneezing.”

“It’s always dirty,” Guzman of #CloseRikers said of his former time at the island. He remembered staying in a dorm with 40 or 50 others.

“Sickness can be caught much faster in the dorm area,” he said. “I have heard about people having the coronavirus even before the news.”

Those who are seeing first-hand what is happening have taken to social media and podcasts to advocate for their patients. One of them is Rachael Bedard, director of geriatrics and complex care service at Rikers. She cares for the oldest and sickest inmates, and is recovering from COVID-19 herself. Correctional Health Services declined to permit Bedard to be interviewed for this piece, but she has spoken via a podcast and other media.

“It’s vitally important that we get as many people out of there as we can,” Bedard has said.

Asked Guzman of #CloseRikers, “How as a city can we not worry about people who are inside?”