Trigger warning: This article contains sensitive and graphic subject matter regarding Black death.

On May 17, 1916 a young racist white man sent his parents a ghastly postcard from Waco, Texas. A sepia photograph on the face of the card centers the charred naked torso of 17-year-old Jesse Washington who had been tortured and lynched in front of 50,000 spectators for allegedly raping and murdering a white woman.

Just below his curled limbs, a mob of hard-faced white men and boys form a calm and proud half circle around their handiwork.

Large cursive writing on the back of the postcard reads: “This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son Joe.”

READ MORE: Suspect’s sister posted photo of Ahmaud Arbery body on Snapchat

A little over 100 years later, Lindsay McMichael, a 30-year-old white woman from Brunswick, Georgia, got her hands on an unedited photo of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery’s lifeless blood-soaked body lying on the street after he was lynched in broad daylight.

Presumably, after her father Gregory McMichael and her brother Travis McMichael hunted down and shot the unarmed jogger while fearing for their lives, they snapped a photo of their kill and shared it with Lindsay and others who continued to circulate it in the local community. News reports indicate that she then posted the photo on Snapchat to expand the audience of viewers.

She tried to obfuscate her own perverse pleasure for Black death by claiming that she’s supposedly a “true crime fan” who didn’t realize that posting the dead body of the man her father and brother killed was in bad taste.

She’s now apologetic. “I had no nefarious intent when I posted that picture. It was more of a, ‘Holy shit, I can’t believe this happened.’ It was absolutely poor judgment,” she said.

She added that because her father and brother “always loved her non-white boyfriends,” murdering Arbery was neither intentional nor racially motivated. “I just want people to realize that we’re not monsters,” she said.

Lee Merritt, the lawyer representing Arbery’s family said, “First you have (Gregory) McMichael sharing with a news station a video of the murder, then you have his daughter sharing an image of Ahmaud’s bullet-ridden body on Snapchat.” He said the McMichael family had engaged in a “weird violent form of voyeurism.”

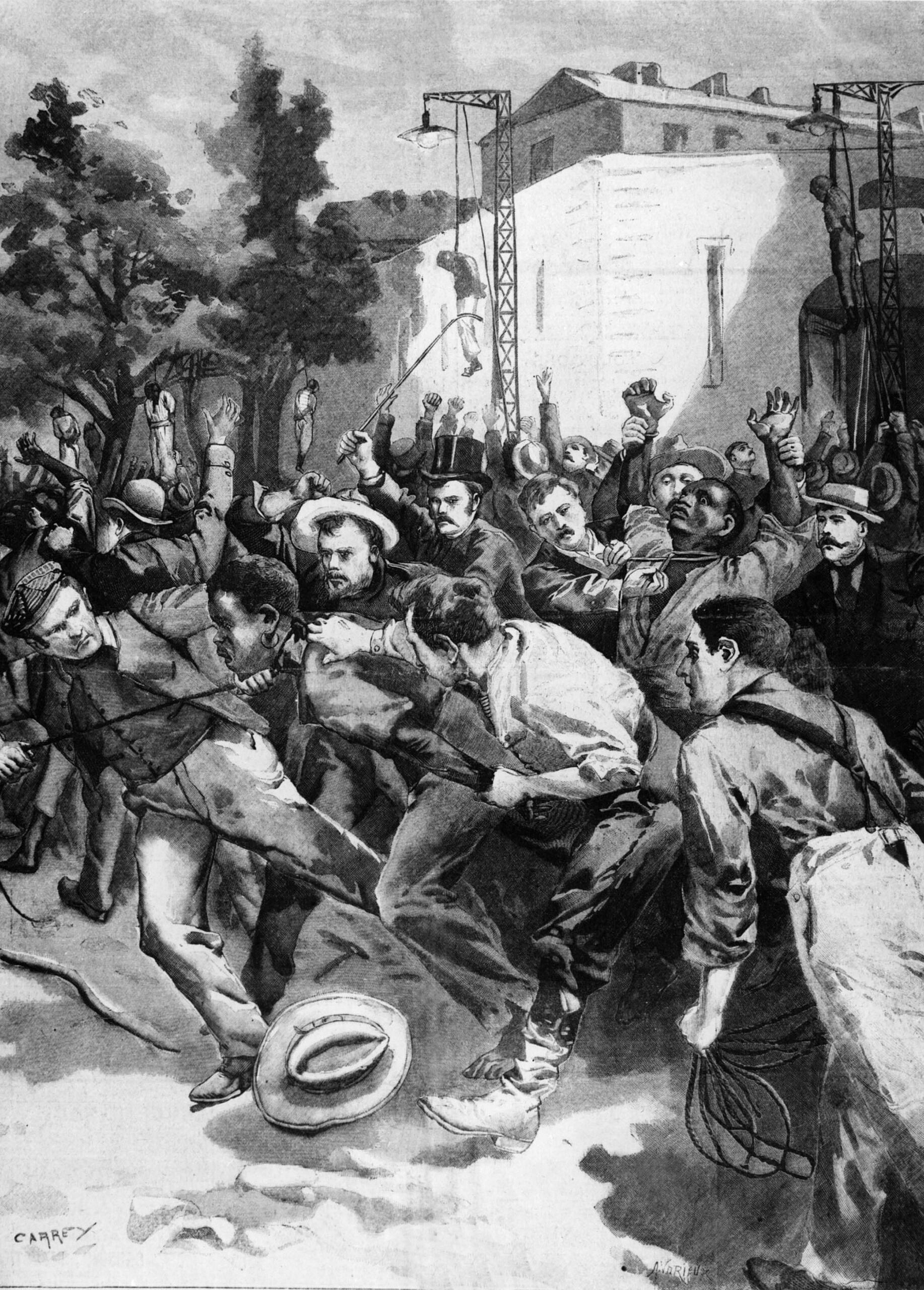

This astute observation by Merritt not only applies to this individual southern white family, but to a broader national visual tradition of white racists who have celebrated Black death across generations. As historians have noted, taking photos of murdered Black people is an indelible part of the choreography of lynching.

READ MORE: Ahmaud Arbery video reminds us Black people still get lynched, even today

In the late 19th and early 20th century, photographers quickly reproduced duplicates of lynching photos and sold them right at the scene of these crimes. Advancements in print technology transformed racial violence into a national sensation.

The development of cheap postcards and the movement of mail through the US Postal System via the railways, along with the national media, turned these visuals into highly-sought-after, mass-produced consumer goods that got shared socially and stored in private family albums and homes. Lynching photos were trophies regarded as objects of white heroism and they were intended to terrorize black communities.

By the 1920s, the NAACP’s campaigns against lynching, along with persistent investigations by the Black press, turned these objects from trophies into evidence of white barbarism and civil rights activism.

Decades later, Mamie Till took control over her 14-year-old son’s mutilated body by using a horrific photo of his battered and swollen face as an indictment against his killers. By allowing Emmett Till’s image to be published on the cover of JET Magazine, Till reframed the national discourse on the Ku Klux Klan and showcased how degraded white supremacists were unapologetic about destroying black children.

Today, with electronic social media and camera phones, images of Black death at the hands of police and white vigilantes have reemerged and get zipped around the world in minutes. These viral videos and images are similar to lynching photography and serve the same symbolic function as trophies.

At the same time, Black people have been engaged in citizen journalism by using camera phones to capture white-on-Black murders and daily terror, whether it is a truck driver or UPS delivery man being harassed on the job, or a man recording his own death-by-cop on Facebook Live.

Though separated by time and place, both Joe and Lindsay and the respective photographers punctuated the lynchings of two debased young Black males by sharing deeply gratifying totemic relics of heroism, sadism, and the lawless privilege of whiteness in America.

In 1916 and 1920, these souvenirs not only offered unmediated access to racial horrors, but they also created a shared experience that united their families, and by extension, white nationalists across America. Sending photos to sympathetic eyes allowed them to assuage perversely curious spectators who missed the thrill of intimately witnessing or participating in the killing of a Black man.

Unlike Joe who witnessed the lynching of Jesse Washington up close and personal, got to pose with the corpse and sent a postcard home to make his ma and pa proud of him for his contribution to white supremacy, having a photo of Arbery’s dead body provided Lindsay with a safe, removed glimpse of the kill while shoring up her sense of safety in her status as a protected white woman.

If we reluctantly give her father and brother the benefit of the doubt, they may have wanted photographic evidence to exonerate them at trial. But once she shared the photo on social media, without subverting it into condemnation, it proves that she is in fact a monster. She is a savage who loves white men who kill black people and she is complicit in the terrorization of Black communities.

Make no mistake about it — Lindsay McMichael felt the emotive power and enjoyed the display of her father and brother’s cruel work of brutal racist communal justice, just like Joe did in 1916.

Stacey Patton is an award-winning journalist and the author of Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America and the forthcoming book Strung Up: The Lynching of Black Children and Teenagers in Jim Crow America.

Stacey Patton is an award-winning journalist and the author of Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America and the forthcoming book Strung Up: The Lynching of Black Children and Teenagers in Jim Crow America.