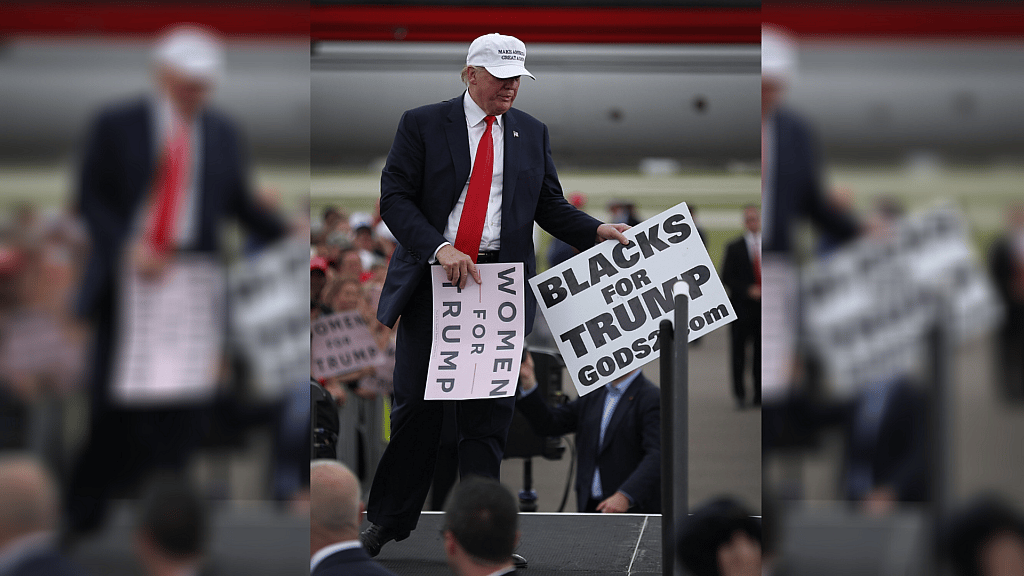

Donald Trump is courting Black male voters.

He is playing into longstanding Republican efforts to shave off portions of Black Democratic support without changing their platform to attract large numbers of Black voters. The goal is not to win Black votes but to weaken Black support for the Democratic nominee who cannot win without them.

Read More: 6 states where low Black voter turnout helped Trump win in 2016

That Black men more consistently show higher support for Republicans than Black women is not new. Black male Republican support increased between former President Barack Obama’s first and second elections. In 2016, Trump attracted 13% of Black male votes. Two times more than Black women.

Polls currently show that 24% of Black men approved of Trump as opposed to 6% of Black women. What is new is that the choices of Black male voters may be decisive in the election outcome. The Trump campaign has invested heavily in Black outreach in battleground states where victories will be narrow and small shifts are enormously impactful.

The Biden campaign is also running ads that are directly aimed at persuading and mobilizing Black male voters. The “Shop Talk” ads featured Black men in barbershops discussing why they should support the Biden/Harris ticket. It is a clear recognition that they believe Trump’s messages are working.

The Trump campaign is trying to surpass their 2016 results. If successful, the difference will come from Black men. He only needs to gain a few percentage points among Black voters to eke out a victory. Four years ago, Trump won Michigan, Nevada and Wisconsin by less than 30,000 votes. He won ten states by less than four percent, which means even an uptick of a few percentage points has the potential to shape the outcome.

Read More: Trump says BLM movement is ‘bad for Black people’

Trump support is especially high among younger Black men who believe Democrats take them for granted and are unable to improve race relations. Black men report feeling overlooked by society except when viewed as a threat. A similar gender gap exists among white Republican voters and suggests Republican positions are generally more attractive to men.

Trump exudes a kind of masculine power that rejects rules and norms but manages to thrive anyway. The campaign’s goal seems clear: to tap into nihilism and chauvinism among Black men who feel dejected enough, disgruntled enough, and sexist enough to be attracted to the style and content of Trump’s message.

Republicans have relied on racial dog whistles for decades that fed racial prejudices. In the Trump era, that dog whistle has become a bullhorn. Trump has referred to Black Lives Matter protestors as thugs. He habitually insults Black women reporters and politicians, most recently referring to Kamala Harris as a “monster.”

She joins a growing list that includes Congresswoman Maxine Waters and journalists April Ryan and Yamiche Alcindor. He has referred to African countries as “shithole countries.” Rather than reconsidering these positions that alienate most Blacks, the Trump campaign is courting a subset of Black male voters.

Read More: What we have to lose: Everything Trump has cost Black America in 4 years

Noticeably during the RNC in August, there was a conspicuous presence of Black men and the virtual absence of Black women. Black men from all walks of life enthusiastically testified to Trump’s generosity toward and concern for Black life. The speakers positioned themselves as independent thinkers who escaped the “mental plantation” of the Democratic Party.

They deployed Biden’s own words that Black people who vote for Trump are not really Black to reinforce the idea that Democrats take them for granted. Speakers touted Trump’s support for HBCUs and his crime reform bill. They noted that Trump represents the party of Lincoln that freed the slaves — as if this iteration of the party hasn’t worked diligently to repel Black voters in exchange for racially conservative white voters.

There is a cynical calculation at play. The Trump campaign understands they may lose among suburban white women and see Black male voters as a way to make up the difference. Stewart Lawrence wrote in The Federalist last October, “Trump’s ability to win even 15 percent Black male support in states like Pennsylvania might provide him the margin he needs, even offsetting some expected losses from suburban women.”

They assume that meager criminal justice reform, overtures to HBCUs and endorsements from Black sports figures will persuade Black men.

This push to attract Black male support is connected to two important political historical moments that point to how conservative beliefs among Blacks are ripe for exploitation by the right. One from the distant past and one more recent.

In Reconstruction, the 15th Amendment extended voting rights to Black men, but all women remained disenfranchised. Legally, Black men entered voting booths to register their political preferences. In actuality, that vote was viewed as a proxy for the entire community.

Historian, Elsa Barkley Brown, explains that many decisions were made communally. Public meetings were held where men, women and children participated with the understanding that Black men would represent those views on their ballot. Additionally, as Black men were harassed, beaten and killed by white mobs, Black women served as their armed escorts to the polls.

When Reconstruction ended and African American male suffrage greatly diminished, Barkley Brown found that Black men began to exclude Black women from power in the community. The loss of leadership opportunities in the public domain led Black men to support more conservative gender roles in the private domain.

Read More: An open letter to Black men on the 2020 presidential election

When they could no longer hold office, be party leaders or govern — all spaces where women were barred — men replicated their male-dominated leadership experience within the Black community by attempting to exclude women from any institutional authority.

Today, Black women not only outpace Black men in political participation but they also outpace them in a host of other socioeconomic indicators. Those Black men who see Black women’s success as displacement can easily find a home in the male-dominated space of the Republican Party. This might help explain the attraction not just for Black men but all men who view manhood as a prerequisite for leadership.

More than that, it might explain why messaging about being overlooked or taken for granted are the appeals that are leading some Black men to support Trump.

More recently, in 2004, Republicans used opposition to gay marriage to appeal to high levels of African American religiosity. Blacks are more likely to attend church services or pray at least once a week and say they have absolute belief in God.

Using connections made through Bush’s faith-based initiatives office, the Bush campaign tapped into African Americans’ long history of social and religious conservatism that sometimes overlaps with white evangelicals.

Black megachurch pastors spoke out against same-sex marriage, and African American Republican support increased tremendously in states where anti-gay marriage amendments were on the ballot. There is no definitive evidence that this increased support was decisive.

According to David Bositis at the Joint Center, if Bush’s support in Ohio had remained at the same level, Ohio would have ended up in the same legal fight as Florida in 2000 as four years previous.

It is important to note that Black men are second only to Black women in their support for Democrats. Even if Black male Republican support increases in 2020, most of the responsibility for a second Trump victory will be attributable to white voters.

Close victories are never about majorities, but the potential of small groups in important states to shape national results.

The power of this siphoning strategy is surgical. In the wake of grave concerns about voter suppression, fears about mail-in ballots, and the continued impact of the pandemic, close political races are increasingly less predictable.

Across the nation, state leaders are engaged in suppressive efforts to limit voter access. Much of which cannot be regulated because the Voting Rights Act has been so weakened.

So both campaigns have to work diligently to maintain current levels of support and counter similar efforts by their opponents.

Melanye Price is Endowed Professor of Political Science at Prairie View A&M University and regular contributor to the Opinion section of The New York Times. Her most recent book is The Race Whisperer: Barack Obama and the Political Uses of Race.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now! TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!