How do you make 300,000 people gathered in Harlem, New York to see legendary Black musicians like Stevie Wonder, B.B. King and Nina Simone disappear?

The 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival was six weeks of Black excellence in music, comedy, and culture. A divine example of communal unity and a manifestation of positive affirmation of spirit. A documentary of that festival, Summer of Soul (…or when the revolution could not be televised), hits Hulu and theaters on Friday, July 2.

First-time director, Roots drummer and bandleader Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, had the ambitious and poignant task of not only unearthing and contextualizing a 50-year-old event, but also explaining why such a glorious occasion was left to rot in a dusty basement.

Thompson, an avid music nerd with encyclopedic knowledge, has himself appeared in several documentaries such as Mr. Soul!, Bad 25, and Finding The Funk. However, the only thing that rivals his own capacity of music information is his endless curiosity of music and the context in which it is created, evident when hearing his weekly podcast, Questlove Supreme.

Both virtues served him well in Summer of Soul and the movie shines because of it. Not only did Thompson gather participants to speak, but he leaned heavily on a select group of concert attendees who could vividly recount the festival, even after 50 years.

Created and produced by Tony Lawrence and directed and captured by Hal Tulchin, the Harlem Cultural Festival at Mt. Morris Park (now known as Marcus Garvey Park) showcased the music of over 20 acts that covered nearly every genre and piece of the African diaspora.

From the pop music stylings of the 5th Dimension, the sophisticated soul of Motown’s Gladys Knight, David Ruffin and Stevie Wonder, the down home blues of B.B. King, to the keening brass of the South Africa’s Hugh Masakala, the righteous improvisations of Abby Lincoln and Max Roach and Afro-Cuban polyrhythms of Mongo Santamaria and the infectious Latin Jazz of Ray Barretto.

The festival was a celebration of the communal unity of Black and brown talent in music and entertainment, as well as a reward for the unwavering spirit and resilience of the people of Harlem.

Dorinda Drake, one of the concert attendees featured in the piece, referred to Harlem as “Camelot” during that time.

“Harlem was heaven to us,” Drake said. “It’s the place where I was safe, happy and made life-long friends.”

The year 1969 was a crucial and transformative time for Black people in America. One year removed from the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the James Brown anthem, “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud),” a shift began as the decade was closing out.

Summer of Soul shows that the influence of figures like Stokley Carmichael and Fred Hampton were helping to shape a new social identify and pride in African-Americans during that time. The people of Harlem reflected the change – in their fashion, their political awareness – as much as the artists.

With the festival series coinciding with the NASA Moon Landing, Thompson expertly juxtaposed the reverent reaction of pride from white Americans about the feat with the bemused indifference from the Black concert goers. One such unnamed attendee told a news reporter his feelings about the moon landing:

“I could care less. Cash that was wasted, as far as I’m concerned could’ve been used to feed poor Black people in Harlem and all over this country.” He felt that the concerts was just as much a part of history as the space walk, if not more relevant.

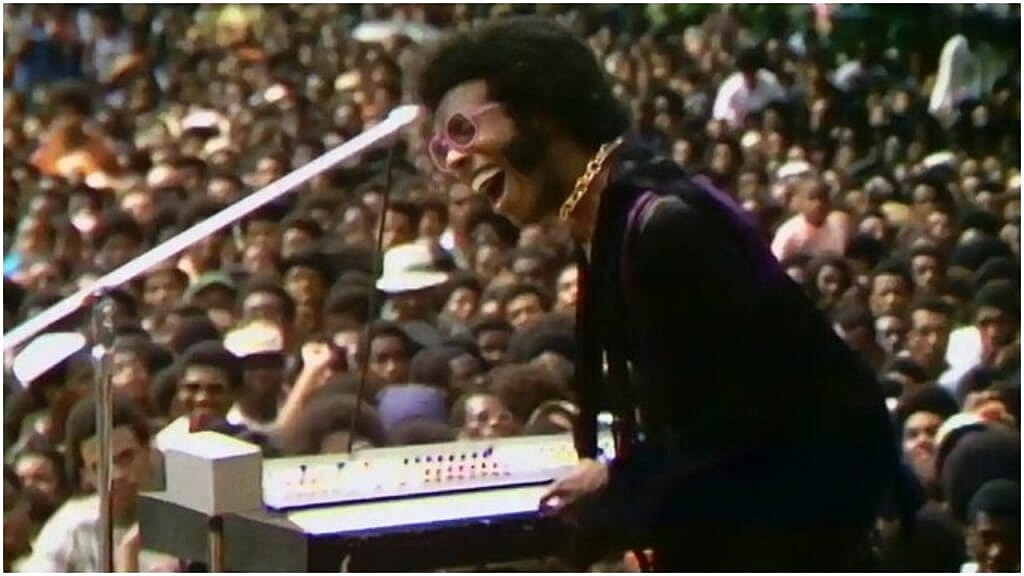

The presence of Sly and the Family Stone, a Bay Area funk band with pop sensibilities that featured musicians who were Black, white and female, was a representation of not only a changing of the guard in music, but also the kind of inclusivity that the nation claims it stands for.

Nina Simone debuted her transcendent anthem, “Young, Gifted and Black,” at this very festival. Gospel legend Mahalia Jackson performed her famous rendition of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand” with Mavis Staples; a meeting of two of the most important voices of the 20th century on one stage in the Blackest place on earth as a requiem to Dr. King, as well as a declaration of spiritual endurance.

As Rev. Al Sharpton stated in the doc, “1969 was the pivotal year when the Negro died and Black was born.”

Ultimately, what separates Summer of Soul from concert documentaries and films is that it confronts the unspoken notion of Black erasure.

“I shot the festival, tried to sell it,” Tulchin said. “Woodstock was the same year, and Woodstock got all the publicity. So, in selling it, I started calling it ‘Black Woodstock. It didn’t help. Nobody was interested in a Black show. Nobody.”

This is where the parenthetic subtitle …or when the revolution could not be televised comes into play. One interviewee stated that Black history is destined to be erased and forgotten. Thompson asks the difficult question about why Black culture is constantly under risk of being swept under the rug of white supremacy and appropriation.

Summer of Soul takes it place besides several documentaries of the past 15 years that unearths important events of Black music history that where left to rot for various reasons.

The aforementioned Mr. Soul! unveiled a largely forgotten all Black PBS arts program that featured geniuses like Curtis Mayfield, Nikki Giovanni, James Baldwin and Lee Morgan from 1967 to 1973. Amazing Grace concert film captured the 1972 recording of one of the biggest selling gospel albums of all time from the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin.

Soul Power revamped a lost film on the music festival that accompanied the 1974 Muhammad Ali/George Foreman fight in Zaire.

All of these films focused on footage, events, and programs that ended more than 40 decades before, but only Summer of Soul spoke about the possibilities of why so much important Black music history has been hidden. This is similar several Black American cities, like Oscarville, Georgia, that were destroyed and literally hidden underwater — a revelation poignantly executed on a recent segment of NBC’s The Amber Ruffin Show.

There are powers at work who recognize the commodity of Black pride and the sight of progress, excellence and self-sufficiency goes to uplifting and galvanizing a community, and will do what they can to stop it from happening.

Summer of Soul isn’t just a documentary; it’s cultural archeology. May it inspire more excavations of Black history as well as real time preservation of Black excellence.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!