Is Afrofuturism the socio-political movement we’ve been building?

From Martin Delany and James Baldwin to Harriet Tubman and Sun Ra. A look into the origins of the Black speculative movement and the implications that come with mainstream appeal.

“Where do you see yourself in the future?” It is a question, a directive, a doctrine, and an aesthetic uttered from the mouths of elders, taught from the hearts of teachers, and posed around the proverbial cookout.

For Kadiatou Tubman, the year was 1998 when she first heard it. The space shuttle Discovery had just made its 25th flight; The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was receiving rave reviews; Beloved and Pokemon were playing in theatres and Microsoft had just become the biggest company in the world — a lot was happening that year.

“It was my 2nd-grade teacher Ms. Doyley,” Tubman recalls. “She had us all close our eyes, just randomly. She’s said ‘I want you to imagine yourself 10 or 15 years from now’ — I remember that. From that moment, I was like, what do you mean we can imagine?”

At the time, Tubman had been commuting with her mom weekly across the Rikers Island Bridge to see her father. By the time 2nd grade at Elijah Straud Academy had started for the Brooklyn student, she was mostly tapped out.

“We were living in poverty and to have a person in my life say imagine yourself in the future and what that could possibly look like. Dream the biggest dream — she put that in me. No one ever asked me to imagine something beyond my current situation.”

Tubman, who now serves as Manager of Education Programs and Outreach at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, says she credits that exercise with ‘Ms.D’ as her first introduction to Afrofuturism. Because for Tubman, Afrofuturism is a “radical imagining of what is possible beyond our current conditions and how we can use imagination, Black culture and Black history to inform that future.”

No doubt, what makes the concept of Afrofuturism radical is that centering of Blackness and Black imagination. It is “a lens on the world but it’s also a practice,” says Ytasha Womack, filmmaker and author of the Locus Award-winning book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. “It intersects Black culture, imagination, liberation, technology and mysticism.”

Afrofuturism As A Lens

Womack started out much like Tubman. “I was an afrofuturist before I knew I was an afrofuturist. I grew up as a kid who was really excited about being a scientist — in a family that really valued history and the performing arts.”

As a young girl, you could find Womack peering into the world of the 1978 musical/fantasy film The Wiz, imagining she too was in a distant land, moving like Katherine Dunham and Eartha Kitt. Sounds of samba, mbalax, house music, and hip-hop are what Womack says influenced her lens on Afrofuturism the most.

“Music and dance has shaped a lot of my perspective around Afrofuturism. Sometimes people say they are not considered to be typical sci-fi references but a lot of music [creates] altered spaces. Dance is a relationship between space and time and music to that extent is — I can see that at play in a movie like ‘The Wiz.’”

This can also be seen in performances and lectures by Sun Ra — known in the mid to late-1900s for creating and facilitating artistically altered cosmic spaces in real-time, through music and movement. As an American jazz composer, poet and creator, he often fused ragtime, swing, be-bop, and theatre to create what he calls “a mirror of the universe.”

Dr. Reynaldo Anderson, Associate Professor of Communication at Harris-Stowe State University and co-founder of the Black Speculative Arts Movement (BSAM), says that pioneers John Akomfrah and Sun Ra helped usher in the Afrofuturism ‘aesthetic’ we see popularized in today’s music, film, literature, and fashion. However, the origins of Afrofuturism were born through Black revolution.

Afrofuturism As A Practice

“This is now a global pan-African project now. The first wave of Afrofuturism as they defined it in the 90s — when they did not have social media — was primarily an African American phenomenon,” says Anderson. “But its intellectual roots go back to Black studies. What we’re calling Afrofuturism is really the Black speculative tradition.”

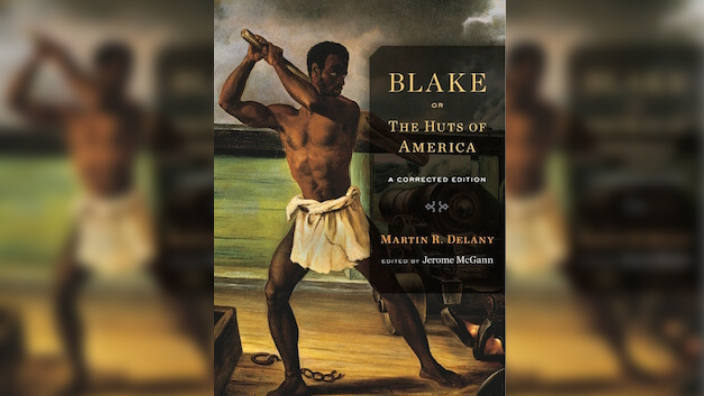

Martin Delany’s 1859 novel Blake (The Huts of America) is what Anderson credits as one of the first Black speculative literary projects on record. Delany, a literary person, physician, explorer, philosopher of history, and military strategist, is most often credited as the father of Black nationalism in America, serving as the first Black commissioned officer of the United States Army.

His novel, however, was a pivotal milestone in Black literature itself. It follows Henrico Blacus, a West Indian man who is stolen away and sold as a slave, but then journeys through the antebellum South, inculcating insurrection. Whereas European science fiction emerges in response to the industrial revolution and the advent of modern science with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), and H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1895), the Black speculative tradition emerges with Delany in response to the transatlantic slave trade, anti-Blackness, scientific-racism, and the pursuit of freedom.

Black speculative tradition, thought, and literature — although it was coined Afrofuturism by Mark Dery in 1993 — is anchored by Delany. He deals with Afrofuturism 2.0, just from a different time.

“2.0 is a 21st century Black or African social philosophy that deals with aesthetics (fashion, visual arts), metaphysics, the social sciences, applied sciences (digital, coding, AI) and community programming,” says Anderson.

Part of the role of AfroFuturists has been to better understand the relationship between the Black experience and technology beyond just stories and gadgets. This intention shifts a question like “Where do you see yourself in the future?” to the directive “See yourself in the future.”

Harriet Tubman’s use of an underground railroad, a secret network of safe houses, was the use of technology. “When you begin to deal with Afrofuturism as a thought process it extends to more than just the arts,” says Tim Fielder, a veteran graphic novelist and author of the recent “Infinitum: An Afrofuturist Tale.”

“It extends to more than just politics. It extends to more than just social mores. It really is just a mode of survival. Because you have to use it.”

Colson Whitehead’s 2017 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Underground Railroad” and Barry Jenkins‘s episodic adaptation of the work are derivatives of that storied tradition. “At the time, it was very advanced technology,” Fielder says. “A technology that allows you to covertly escape away from bondage. That’s what it was. It’s no different from cannons.”

Fielder asserts that this practice of Afrofuturism is more ubiquitous than we think. American novelist, playwright, and activist James Baldwin alluded to this survival tactic. In his 1963 interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark for the series “Perspectives: Negro and the American Promise,” Baldwin was asked a dichotomous question. “Are you optimistic or pessimistic” about the future of the country?

“I can’t be a pessimist because I am alive,” Baldwin explained. “To be a pessimist means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter. So, I am forced to be an optimist. I am forced to believe that we can survive, whatever we must survive — the future of the negro in this country is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country.”

Baldwin, a self-proclaimed witness to the Black American experience, is exasperated in his response. It could easily be interpreted as defeated optimism “because so much of our history has been buried, forgotten, or burned down,” continues Fielder. “As an afrofuturist, I can’t always, all-the-time operate as a futurist. An afrofuturist is forced to deal in the past, present, and future simultaneously because you’re trying to reconcile all this information, misinformation, missing information — trying to fill in the blank. And that’s what makes it speculative in the real world sense and speculative in the fictional sense.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was a social scientist, mastering and molding media, language, and community organizing into advanced technology. He spoke of Black futures, Good vs. Evil and community power in notable speeches like “I Have A Dream” and “Our God Is Marching On,” effectively streaming and narrating the Black experience on television screens across the nation. This, to many critics, activists and journalists, was the catalyst for desegregation.

“The civil rights revolution in the South began when a man and the eye of the television film camera came together,” wrote the journalists Robert Donovan and Ray Scherer in their 2008 nonfiction book on television news, Unsilent Revolution. King was at the precipice of the rise of television news, granting news programs a focus and lead for events breaking on the frontlines of the Civil Rights Movement in exchange for high exposure on television sets.

Even Chairman Fred Hampton of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party shared speculative thoughts and intentions, constantly reiterating “There’s power anywhere there’s people.” This is an example of seemingly hopeless Black people employing technology in the absence of actual tech.

Afrofuturism and The Black Speculative Movement

Afrofuturism is only part of the Black Speculative Movement, a tradition simultaneously creating and gestating the futures of Black people — it is not conjecture, fluff or simply another aesthetic used to blanket capitalistic structures. Afrofuturism, at the core, is a survival and prosperity tactic and a socio-political movement.

“This has been going on for centuries,” says Kadiatou Tubman, referencing pivotal leaders like Marcus Garvey, Sojourner Truth and Nichelle Nichols. “I’m getting emotional because I’m thinking about our ancestors who were enslaved and they saw the future. It’s a part of a whole lineage of people looking into the future and imagining a different way and not saying this is all that there is — that’s what keeps this going. People forget; it’s extremely radical. It’s abolitionist.”

Over the last decade, the concept of Afrofuturism has gained sharp traction. Search queries and topics including “what is Afrofuturism,” “black panther afrofuturism” and “Octavia Butler” have grown by more than 5,000% — thanks in large part to a boost from the box-office darling Black Panther, one of only seven films to gross upwards $600 million domestically.

Afrofuturism plays a much larger role in the efficacy and hope of Black Americans today. It shows up as entertainment, but rings as a political platform with intention; being Black is often a political act itself. So much throughout history, Black Americans were not allowed to have ownership over their lives in the present — being stolen, purchased, and resold through carceral and capitalistic systems. Afrofuturists, all a part of the diaspora, recognize it as a tool to actually write, create and own their futures in the midst of fighting for their present.

And even then, Afrofuturism dwells beyond the need to have ownership over it. It rests within the discomfort of celebrating Juneteenth as a federal holiday without proper national atonement and recompense; it is shared through a palpable sentiment of hope for a better Black future; and it is catalyzed within the minds of Black children who are given the freedom, support, and instruction to imagine.

Riley S. Wilson is the writer and director of the award-winning sci-fi/drama series Little Apple and founder of Little Apple Universe, a digital streaming platform that blends education with entertainment to provide TV programming, comics, and racial/social justice curriculum to schools. The LAU experience has appeared at the Apollo Theater, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and countless schools and youth organizations.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s “Dear Culture” podcast? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire and Roku. Download theGrio.com today!