History, Unwhitened: How America stole Black history

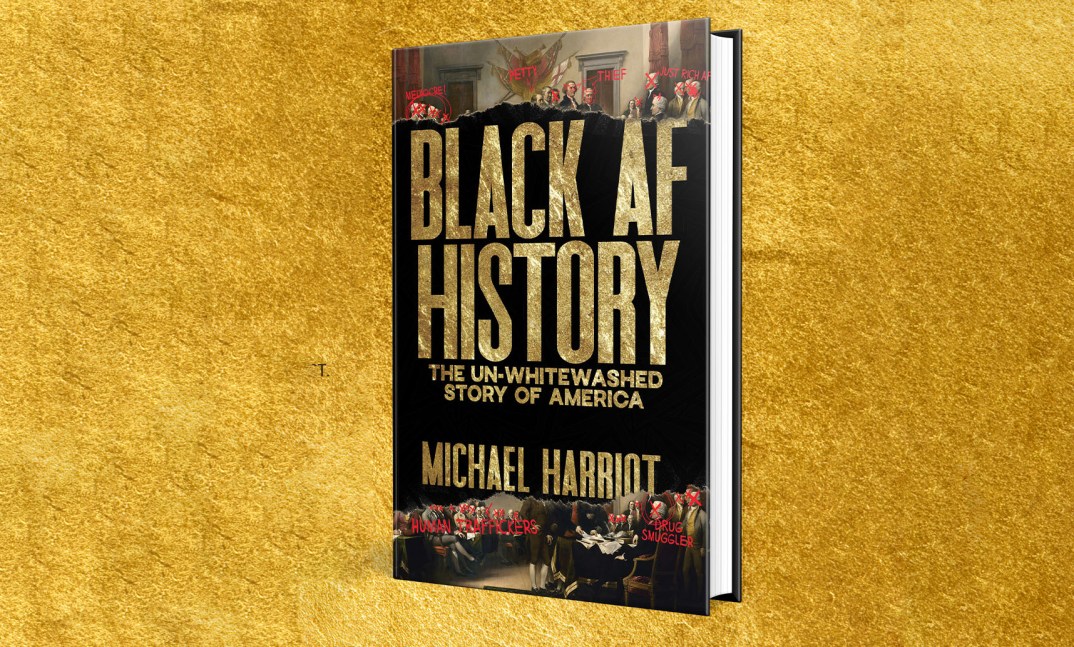

Michael Harriot explains the difficulty of unwhitening history in an excerpt from his bestselling book, "Black AF History: The Un-Whitewashed Story of America."

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Something was wrong with me.

I was always “in a daze.” I couldn’t sit still. Long before I was eventually diagnosed with the most acute form of attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, I was just “hyper.”

Although we now understand that ADHD is a common mental neurodevelopment issue that affects millions of children, I was diagnosed as “bad.” My mother tried to combat my hyperactivity with diet, forbidding my sisters and me from eating anything that contained Red Dye No. 5 or sugar (except on Fridays, when I could choose between a roll of Life Savers or a pack of Chiclets). In fifth grade, I spent months in the Harriot household’s version of juvenile house arrest when I was caught tracing my mother’s name on an interim report that described me as “smart but have trouble following directions.” The third deacon-in-command at church nicknamed me the “absent-minded professor.”

And then there were the coats.

Coats were the bane of my childhood existence. I always lost them. I left them on church pews, in cars, and especially at school. And because coats are the most expensive part of a kid’s wardrobe, I have received more dressing-downs from my mom about coats than anything except my propensity to forget to pull the garbage can to the curb on trash day. If there is a heaven for jackets, it is almost certainly filled with the misplaced winterwear purchased by Dorothy Harriot. I always, always lost my coat.

So, in fifth grade, when I begged my mother to buy me a “goosedown” — a feather-filled ski jacket with removable sleeves that had become the latest fashion–of course she gave me a lecture about how I’d have to suffer frostbite and hypothermia for the next two winters if I lost that puffy coat. The day my mother bought that goose-down from the Army Navy store was the second-happiest day of my sartorial life, exceeded only by the parachute pants and Ghostbusters tee I received for my birthday a few years later.

One day, I was walking home from elementary school, which required me to walk past the hangout spot where all the thugs cut school to smoke cigarettes and look at “nekkid magazines.” I was in one of my trademark dazes when the scent of menthol-laced smoke alerted me to the fact that I was being followed. By the time I tried to run, it was too late. This crew surrounded me and demanded I give up the goosedown. I thought of my mother’s wrath. I thought of all the long-lost jackets from the past, from the bootleg Members Only to the Sears Toughskin with corduroy sleeves. I thought of my mother’s frostbite warning and the days in middle room solitary confinement in my future.

I refused.

They beat it off me.

I struggled so hard that, while they got the body of the jacket, they couldn’t get the sleeves. But what good are warm arms when you’re walking home with the rest of your body fighting off cold? Of course, I kept it a secret. I wasn’t embarrassed about the mugging as much as I was afraid of my mother’s wrath when she realized that I no longer had the item on which she had spent an entire $56. I knew she wouldn’t buy the mugging story. I had to get it back before she found out. So instead of telling her that I had been robbed, I told my two older cousins, Fred and Squeak, along with my best friend, James Bond.* They were already in junior high. They probably knew the culprits. A few days later, as I shivered home from school, avoiding the Newport shortcut, they yelled out to me to come over.

* We called him “Double-O Seven,” which was eventually shortened to “Double-O.”

They had found it!

There, wearing my sleeveless goosedown, was my next-door neighbor, Freaky-D. Freaky-D wasn’t big, but he was fearless. At thirteen, he was already smoking marijuana and drinking Colt 45. Apparently, he had been casing my goosedown for months. Surrounded by my investigative squad, Freaky-D swore that he had owned the coat for over a year. His friends, whom I recognized as the muggers, backed him up. They corroborated his story, insisting that he had had the coat for over a year. After a few minutes of interrogation, Double-O, Fred, and Squeak bought his story and let him go. As they walked away, Freaky- D let me know it wasn’t over.

“I’mma remember this, Mikey,” he yelled. “Freaky-D don’t steal!”

The next morning, I was called into the principal’s office. Sitting there was my mother, along with Freaky-D and the vice principal of the Hartsville Junior High School. With tears in his eyes, Freaky-D recounted how I had masterminded the plot to convince my friends to steal his jacket. As illogical and preposterous as it sounded to me, to the jury in the principal’s office, Freaky-D’s testimony was perfectly plausible.

I vehemently objected to Freaky-D’s lie, explaining that there was no evidence for this wholly untrue story. He was the real jacket thief. Unbeknownst to me, Freaky-D had proof, which was why my mother was summoned to the school. Staring a hole into my soul, she reached into my bookbag and pulled out the evidence that confirmed the true his- tory of the goosedown jacket . . . the sleeves of which matched perfectly.

What you are about to read is a true story. The names have not been changed to protect the guilty.

In most history books, America is colonized by European “settlers.” In chronicling this nation’s past, historians recognize that the English, Dutch, Spanish, and French colonists are human beings with different backstories, cultures, and motivations. We know the political incentives, economic concerns, and social mores that explain away the theft, violence, and genocide they committed against the savage silhouettes that we are too unbothered to name. The people and cultures whose blood water the stolen landscapes are usually dehumanized by simply remaining anonymous. The stolen Africans are not Akan or Nyamwezi; they are just “slaves.” The various indigenous nations who were extinguished are never Oceti Sakowin or even Iroquois; they are just “Indians” or, at most, “Native Americans.” Yet, somehow, the states and colonies that replace them have borders, legatures, and distinguishable features.

Black AF History does not upset this timeless tradition of American scholarship. It uses the same scholarly conventions to which we have become accustomed. To make sure the reader isn’t disoriented by a new historical standard, this book recognizes that the English, Dutch, Spanish, and French land thieves are just “white people.” While it may sometimes seem abrasive, confrontational, and even dismissive, this book recognizes that the only difference between a burglar and a “settler” is who writes the police reports. In fact, the only difference between the Black AF version of history and the way America’s story is customarily recounted is that whiteness is not the center of the universe around which everything else revolves.

While this book does not seek to deify whiteness, it also does not obfuscate the flaws of Black heroes. In this history, Martin Luther King Jr. is a human being who is sometimes afraid. Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois are rivals, but their ultimate goal is the same—to get free. In this book, enslaved Africans are not victims, they are warriors from the Ashanti Kingdom and the founding fathers of the Gullah culture and the creators of America’s first democracy.

And while this book is not the complete history of Black people in America, it acknowledges that too much has been stolen for that to ever exist. In this book, there is no America. In this book, the country we know as the United States is just a parcel of land that was stolen and repurposed as a settler state using European logic and the laws of white supremacy. This book is a story about a strongarm robbery. It is about family and friends trying to recover what was stolen. It is the testimony, and the verdict that a jury of our peers has never heard.

I can do that in my history. Freaky-D taught me that.

Years later, I asked Freaky-D about that jacket. He acknowledged that he knew it was stolen when he bought it from the thieves. According to Freaky-D, the guys strung him along about the sleeves for days, promising that they would eventually be delivered. He claims he didn’t know the coat was mine until Fred, Double-O, and Squeak confronted him about it, which is when he came up with the plan to get the sleeves. And because all history is infused with the historian’s values, in Freaky-D’s version of history, receiving stolen property doesn’t make him a thief.

Like Freaky-D, America don’t steal.

This is the Black AF history of America.

This book is the sleeves.

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His NY Times bestseller, Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America, is available everywhere books are sold.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!