Group of mothers push for government support of Black microschools

"Microschools" are a hybrid of homeschooling and traditional schooling in which class sizes are small, typically fewer than 15 students, and the schedule and curricula are tailored to the needs of each student.

A group of Texas moms took matters into their own hands after claiming public schools were ill-equipped to offer a learning environment completely safe for Black children or support their culture and identity — and they’re now urging the government to assist in expanding their efforts.

According to the Texas Tribune, Sharby Hunt-Hart, Chantel Jones-Bigby, and Anna Sneed homeschool their daughters, designing lesson plans to fit each girl’s academic needs and adjusting their pace when a child struggles. They want to expand their group and establish a “microschool” that serves more Black boys and girls in the area.

“Microschools” are a hybrid of homeschooling and traditional schooling in which class sizes are small, typically fewer than 15 students, and the schedule and curricula are tailored to the needs of each student.

“What we’re doing with the microschools is decolonizing what we know of education,” said Jones-Bigby. “And we have so much less resources. We’re working with so much less, but yet, our children are doing academically, emotionally better.”

The women already have other parents interested in taking their children from private and public schools to join their collective. However, to put their plan into action, they need the Legislature to establish education savings accounts, a voucher-style scheme through which families might access state funding to pay for private school or alternative education settings.

Education savings accounts would allow families to opt out of the public school system and use taxpayer funds to pay for alternative learning environments such as microschools. The three mothers could use the cash to help them scale up and pay for training materials and a dedicated learning environment.

Still, legislators at the state Capitol have varying opinions about utilizing taxpayer funds for non-public education. Democrats and rural Republicans in the Texas House have traditionally opposed voucher plans, arguing that any education dollars should go to public schools that are struggling financially due to the pandemic and inflation.

While supporters believe education savings accounts provide parents with better academic options, opponents argue that vouchers entail less money for public schools, which already need more funds to improve teacher pay and satisfy other demands. Schools receive less cash when kids leave public schools for alternative education settings because state funding is related to student attendance.

Jones-Bigby believes the public school system should accept the truth – it frequently fails to serve Black children well.

Even for minor transgressions such as dress code violations, Black students in public schools face harsher penalties than white pupils. According to studies from the American Psychological Association, this harms their sense of belonging at school and their academic achievement years later.

In Texas, 26% of children who earned in-school suspensions in the 2018-19 school year were Black, although accounting for just 13% of public school enrollment. This year, a Black teen at Barbers Hill High School in Chambers County was suspended and sent to a disciplinary program for his hairstyle, putting to the test a new legislation prohibiting hairstyle discrimination based on race.

Jones-Bigby is concerned that if schools do not reconsider how they discipline and treat Black students, they will lead them astray.

“Most of the day, they spend it in an environment where they are devalued. They are lost. They are waiting for direction,” said Jones-Bigby. “Someone has a plan for my child when they are lost. It involves an orange suit and a 4-by-4 box.”

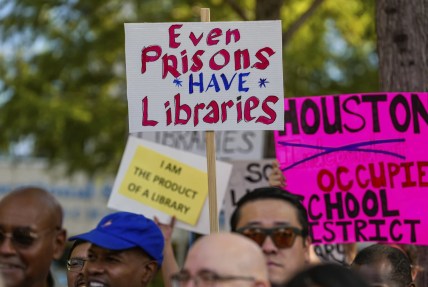

In Arizona, 40 Black mothers convened in 2016 with the same concerns for their children – who were bullied at school and did not feel supported by the instructors – ready to demolish what they term the school-to-prison pipeline. The mothers began by urging school districts to develop a re-entry-after-suspension strategy and look for alternatives to suspension as a disciplinary tactic.

They established their microschool in 2021, commonly known as outsourced homeschooling. The survival of Arizona microschools is dependent on the state’s education savings account program.

While the Texas Legislature and Gov. Greg Abbott debate whether to create such a program, the fate of school vouchers and the moms’ plans hang in the balance. After similar legislation failed during the regular session, the governor, a strong advocate of school savings accounts, called a special legislative session last month to encourage lawmakers to adopt a voucher plan.

Abbott has vowed to summon another special session if lawmakers do not act on vouchers and has threatened political ramifications for those who get in the way during next year’s elections.

Supporters like Jones-Bigby believe student departures will force public institutions to adapt, contending that additional educational alternatives are needed for families to guarantee that their children receive the education they require.

“As much as I would love the public school system to work for my child, it doesn’t,” Jones-Bigby said. “Am I responsible to the system or am I responsible to my child?”

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!