It seems like a twisted yet accepted rule of thumb: The richer your zip code, the better your public schools will be.

In the United States, it’s widely understood that because taxes fund local school districts, one of the paths to the American Dream is buying a home based on how good schools are, which usually means having the means to do so. Due to a history of racism and segregation that kept Black families out of the wealthiest and usually whitest neighborhoods, this has often led to the worst-performing and most under-resourced school districts being concentrated with the poorest and most socioeconomically disadvantaged children.

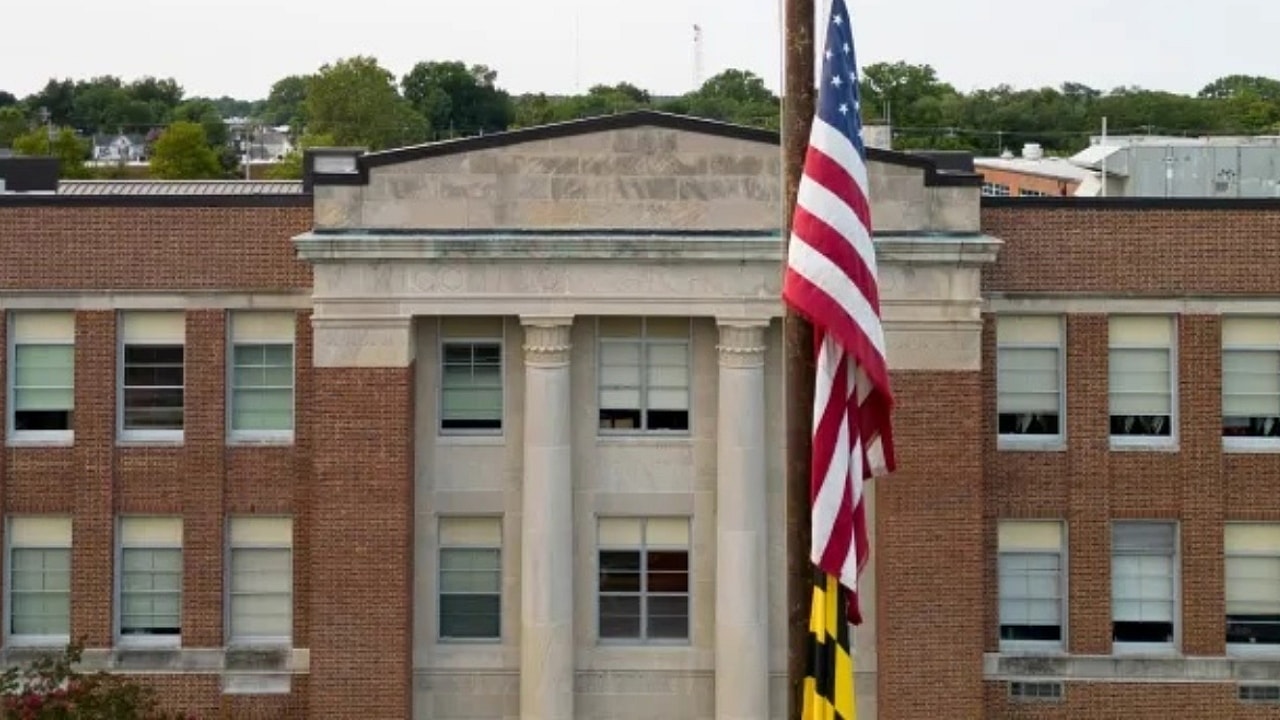

In 1981, representatives of 20 children in poor school districts in New Jersey sued the state over the funding disparity, alleging that the state’s school finance system was a violation of constitutional rights because it left these districts unable to meet their students’ needs, relative to the richer suburban districts.

The case, Abbott v. Burke, would ultimately land before an administrative judge who declared the state’s approach to funding unconstitutional and demanded a remedy that would ultimately impact 31 districts, known as “Abbott districts.”

Decades later, the impact of the Abbott ruling remains relevant, as New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy is facing litigation over the lack of a plan to address long-term funding needs for building repairs in some Abbott districts today. The influence of Abbott can also be seen in the expansion of free preschool education across the state.

Could Abbott v. Burke provide a blueprint for other states to dismantle the persistent school funding inequalities?

“The approach is one that’s rooted in equity,” said Dr. Chimaobi Amutah, a Trenton, New Jersey, native and Abbott district school graduate who was a teacher before creating educational consulting firm COA Education Solutions. It’s “very different,” he said from what he encountered “in Mississippi, where there was no such a court ruling, and districts were funded disproportionately. I believe in the spirit of it.”

Amutah said that New Jersey’s reputation for having some of the best public schools in the country is, in part, a product of rigorous attempts to close funding gaps between schools.

“We have this ongoing joke in New Jersey that we export so many high school graduates to other states and cities and even statewide university systems,” he told theGrio.

But despite the success of the plaintiffs in the Abbott v. Burke case instigating lasting change, it doesn’t mean tinkering with school funding approaches has been welcomed by everyone.

In 2016, then-Gov. Chris Christie blasted the state’s school funding program under Abbott, claiming that the billions in extra dollars being redirected to high-poverty districts was not paying off.

“We accept subpar performance, and we pay a fortune for it,” Christie was quoted as saying in the Courier Post.

From Christie’s and other critics’ perspectives, the overall achievement gap had not been closed over the course of 10 years, despite some improvement in graduation rates.

Of significant concern to Christie and the constituents he sought to court with his critique was the skyrocketing tax costs for funding schools that the wealthiest districts saw redirected to poorer districts. To these taxpayers, the money they were spending on other people’s children wasn’t well worth it.

Recommended Stories

“Those that have enough money to purchase a home at all, let alone a home in a particular type of community,” Amutah said, “those individuals have better-funded schools, which is kind of re-creating the cycle of inequality and privilege in their children and offspring. It just creates pockets of inequality, pockets of homogeneity.”

The resistance can even be described as a scarcity mindset despite what seems like a wealth of resources for some.

“People want what’s best for their kids, which is understandable,” Amutah explained. “The pot is finite. Whether what we generate internally as a state or whether what we get from the feds in terms of school funding, that part is finite. So, the more one district gets, the less another gets. And we can’t really do anything about that.”

Despite some underperformance in Abbott districts, there are specific Abbott districts that have seen remarkable success, and some other states that have taken the Abbott v. Burke approach have won victories. Last year in New Hampshire, a judge ruled that the per-student funding amount should be raised from $4,100 to $7,356.01. The judge also ruled that wealthy towns that were collecting property taxes for schools and keeping the leftover funds now needed to redistribute the money to poor schools in other parts of the state. An appeal to the state Supreme Court is expected.

Other states have sued with similar arguments, including Arizona, Pennsylvania, Wyoming and Washington.

Amutah said that while lawsuits are one model for spurring change, an even more revolutionary model may be found in doing away with the borders that cause these inequalities in the first place.

“The most radical idea on some level would be to have countywide school systems,” he told theGrio. The practice has been implemented in areas like Wake Forest, North Carolina, where student performance went up drastically after the mostly Black city and mostly white suburban school district merger in 1976.

“The research shows that if you did that, and you more evenly dispersed students with the greatest challenges across different schools throughout a system, and they weren’t just necessarily in particular enclaves, the benefits to students would be extreme,” Amutah said. “All the research is definitive on that. Those are benefits typically in terms of academic outcomes, high school graduation rates, college attendance, long-term career earnings– all those positive things.”

He argues that the biggest challenge in the school funding reform debate will be not just changing laws, but changing mindsets to embrace the shift. It’s what makes the school funding debate as much an issue of civil and human rights as it is about dollars and cents.

“Security for the entire society is rooted in everyone having opportunities, experiences and resources to live there. So, it’s all relative,” Amutah contends. “We have to contribute to the well-being of others because at the end of the day, it also is something that’s in our self-interest.”

Natasha S. Alford is VP of Digital Content and a Senior Correspondent at theGrio. An award-winning journalist, filmmaker and TV personality, Alford is author of the forthcoming HarperCollins book, “American Negra.” Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @natashasalford.