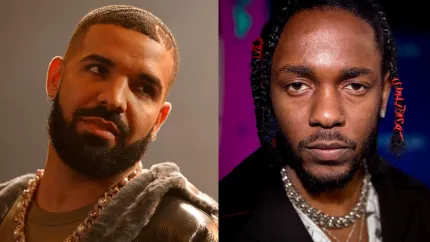

The beauty of hate: A literary analysis of Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Euphoria’

OPINION: Kendrick Lamar’s latest beef ballad elevates the diss record subgenre to an art form and should be discussed that way.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Hate: (noun) intense hostility and aversion usually deriving from fear, anger, or sense of injury. extreme dislike or disgust

(verb) to feel extreme enmity toward: to regard with active hostility

— Merriam-Webster Dictionary

On Tuesday, rapper Kendrick Lamar set the internet abuzz with “Euphoria,” the latest clapback in Lamar’s ongoing rap beef with Aubrey “Drake” Graham.

One of the most remarkable things about this feud is that it is not about a thing; it is about an idea. Unlike Tupac versus Biggie or Gucci Mane versus Young Jeezy, this conflict did not begin with an act of violence. The origin story doesn’t have a breakup like the squabble between NWA and Ice Cube or Lauryn Hill and Wyclef. In a sense, the beef between K-Dot and Drizzy over who should be considered the second-best rapper alive (Black Thought is still alive and rapping, right?) is really about Black excellence, which is partly why it sent everyone into a state of …

You know.

First of all, let’s get this out of the way. While every person is free to have an opinion of any art form, not every opinion is valid. Just as everyone has the right to believe that the Earth is flat or that systemic racism is not real, I have the right to tell white people and non-astronomers: “I don’t value your opinion on this subject.” And, because Drake fans rank his lyrical profundity somewhere between the Declaration of Independence and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, it is perfectly fine to disagree with my colleague Touré’s opinion that “Euphoria” is “one of the best diss songs in hip-hop history.”

As a poet, I have always believed that the practitioners of hip-hop are unquestionably the greatest wordsmiths and musicians of all time. They combined music and poetry to create a new art form, engineered instruments, invented language and built business models. In my opinion, Lupe Fiasco’s “Kiosk” is a more complex poem than Shakespeare’s “To Be or Not to Be.” A high school band can play anything Beethoven ever composed, while I can count on one hand the number of earthlings who can replicate what DJ Jazzy Jeff does on stage every night. If Edgar Allen Poe was so great at rhyming, why doesn’t he have a single 10-minute freestyle?

However, there is a difference between an opinion and a critique. The former is just a value judgment based on a person’s individual preference. Conversely, a critique is an informed analysis using a set of commonly accepted objective standards. It does not necessarily require a value judgment or conclusion on whether it is good. And, when it comes to the latest slice of beef from Clapback Kenny, whether you’re Black or white, Drake-onian or KenFolk, anyone who listened to “Euphoria” can objectively agree on one inarguable fact:

Kendrick Lamar hates Drake.

Of all the sundry chemical reactions the human brain produces, perhaps hate is the purest, most human emotion of all. A wildebeest can fear a lion and even a puppy can love its owner, but hate is uniquely human. While its byproducts are often toxic and unhealthy, hate can also be useful. Hating an opponent — or even the idea of losing — can motivate an athlete to elevate their play. It can poison the minds of a lynch mob but it can also inspire others to fight oppression.

Most importantly, this universally relatable passion is also the foundation of the most beautiful art. If not for the hatred between the Montagues and the Capulets, “Romeo and Juliet” would be a cute little play about a teenage crush. Without the smoldering embers of rage that hatred sparked, Killmonger would just be another second-generation African immigrant who grew up in a fatherless home. Kobra Kai hates Daniel-san as much as Obi-Wan Kenobi despises Darth Vader. Shirley versus Barbara is the same as Tom versus Jerry or Jason Whitlock versus his Blackness.

Hate is beauty.

While it’s OK to enjoy rap music for the wordplay or its ability to make you dance, if you are one of those people who don’t like diss songs, I do not respect your opinion on this subject. Beef is a foundational element of hip-hop. It’s why people love battle rappers and why breakdancing is an Olympic sport. And, in a genre and a culture partially founded on competition, “Euphoria” should be discussed as one of the greatest artistic expressions of hate we have ever seen.

The title of the song refers to Drake’s role as executive producer on HBO’s “Euphoria,” which follows the exploits of a group of California teenagers dealing with drugs, sex and, well … more sex. This might be a shot at the unfounded rumors swirling around 6ix God’s friendships with teenage white girls. Before the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet begins, the song opens with Richard Pryor’s climactic scene from the 1978 musical “The Wiz,” where the great and powerful Oz reveals himself to be a scam artist. But instead of hearing Pryor scream: “Everything you say about me is true!” Lamar plays the clip backward.

Kung Fu Kenny kicks off the diss by painting Drake as a scam artist acting like a rapper who makes soulless, uninspiring music — a criticism that is often leveled against the Toronto rapper. Over a Teddy Pendergrass sample,1 Lamar explains his plan to neutralize the “Degrassi” actor’s “superpowers,”2 noting Drake only began talking about his personal life after hearing Kendrick’s celebrated, intimately personal album “Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers.” Not only does King Kunta paint Drake as a “degenerate”3 culture vulture with money and power but no respect, but throughout the song, he also equates Drake with Satan.4 But that quadruple entendre is nothing compared to the line: “Got a Benjamin and a Jackson all in my house, like I’m Joe, OK?”5

- This may be a reference to Ghostface Killer’s Teddy Pendergrass-backed rant at Caucasian rapper Action Bronson. Pendergrass, like Drake’s character in Degrassi, was wheelchair-bound.

- In the song “For Free,” Drake borrowed an old Too Short line to explain: “I must have superpowers …”

- In geometry, a degenerate shape is essentially a straight line. Kendrick, however, says he can still predict Drake’s angles because, like a degenerate, Drizzy has no weight or mass.

- He says Drake’s homeboys sold their souls to become “demons” for a “Hellcat,” which is also a model of a Dodge Challenger that comes in a more powerful version, the Dodge Demon. “DeMun” is also the middle name of Future, who produced Kendrick’s first shot at Drake, “Like That.”

- “Benjamins” refers to Benjamin Franklin, slang for $100 bills and the 1972 Michael Jackson song from the movie “Ben,” which is about an angry rat (Look, it was a simpler time). “Jackson” not only alludes to Drake repeatedly comparing himself to Michael Jackson, but it also refers to President Andrew Jackson and the $20 bill. By calling himself “Joe,” he’s essentially calling Drake his son while evoking the name of another powerful man with a Benjamin and a Jackson in his house — Joe Biden.

If you’re counting, that single bar contains a sextuple entendre.

Usually, Kendrick’s music is a mosaic of metaphors and multilayered allegories and, at this point, “Euphoria” is just that – a densely packed, pointed rebuke by a highly skilled rapper. But those complex lines are just precursors from where Lamar pivots from making a simple diss record into transforming hate into art. In the song that began this whole beef, “First Person Shooter,” Drake portrayed himself as a fake gangster, bragging that he would “click the trigger on a stick [gun] like a high beam.” In his subsequent “Taylor Made Freestyle,” Champagne Papi (as A.I. Snoop Dogg) claimed Kendrick has “never been to jail … Never shot nobody, never stabbed nobody, never did nothing to no one …”

This is what Kendrick hates.

Aside from rapping about growing up in a poor neighborhood filled with gang violence, Kendrick often talks about the trauma of witnessing a murder at 5 years old. In “Blacker the Berry,” “Hol’ Up,” and “m.A.A.d city,” the “good kid” even seems to reference an incident from his teenage years, when he may have even killed someone, which explains why he prefers to stay “low” and refuses to fear “the reaper.” This is also where K-Dot summons his enmity, rapping:

I hate when a rapper talk about guns, then somebody die

They turn into nuns, then hop online, like “Pray for my city”

He fakin’ for likes and digital hugs

His daddy a killer; he wanna be junior; they must’ve forgot the shit that they done.

– Kendrick Lamar, “Euphoria”

Music

From there, Kendrick pulls out a flamethrower. He calls Drake out for how he’s raising his son. He brings up how Drake has repeatedly thrown sneak disses at Black women like Megan Thee Stallion, Rihanna and Serena Williams. He tells him he makes songs that “pacify” his white fans. Kendrick even accepts beef on behalf of Pharrell Williams (To be fair, the Compton emcee admits that he prefers Drake’s singing discography). When it comes to high-level dissing, all of this is par for the course. Most people have been accused of being worse things than an anti-Black, cultural-appropriating scammer. I’ve been called the n-word three times a week and was once sucker-slapped (which is much worse than being sucker-punched). But of all the animosity, scorn and malevolence I have experienced, the one thing I have never seen is what Cornrow Kenny did in “Euphoria.”

He just said: “I hate you.”

The list of things Kendrick hates about Drake includes:

- Drake’s Canadianness

- Purchasing Tupac’s ring.

- How Drake appropriates language, accents and Black American culture

- How he treats Black women

- His plastic surgery

- The way Drake walks

- The way he talks

- The way he dresses

- The way he sneaks disses

- The way he says the word “nigga”

Publishing an itemized list of the reasons for your hate is the most savage piece of poetry since a young Maya Angelou wished “that Gabriel Prosser and Nat Turner had killed all white folks in their beds and that Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, and that Harriet Tubman had been killed by that blow on her head and Christopher Columbus had drowned in the Santa María.”

Imagine how much loathing and animus a skilled wordsmith and Pulitzer Prize winner must have in their heart for them to set aside their entire vocabulary and distill their hatred to its most concentrated form. “I hate you” is awesome in its simplicity. It is more offensive than “yo mama” and more despicable than “That’s why I fucked your b**ch, you fat …” It is the most authentic way to express the most human emotion.

And yes, it is beautiful.

Because, after all, what is art?

An accurate portrayal of someone’s pain is sometimes as beguiling as joy and humor. Some songs are supposed to make you cry. A well-written tragedy is as enchanting as a perfectly executed satire. In fact, all Black art, including the blues, jazz, and standup comedy, has an element of pain and suffering.

But not like this.

This was the most brutal version of hip-hop as an art form. It was the opposite of a love song; a hate psalm at its most pristine. He didn’t even attempt to besmirch the rapper we know as Drake; he attacked Aubrey Graham and who he is as a person. “Euphoria” makes the case for why King Kendrick deserves to wear the crown Drizzy tried to claim. But as an adversary and rival, Lamar was cruel and ruthless and merciless and cold-blooded and mean and filled with rage. He did not just make a diss record about a person; he created an artistic act of terror, a magnificent homicide.

And Damn, was it beautiful.

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His NY Times bestseller Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America is available in bookstores everywhere.