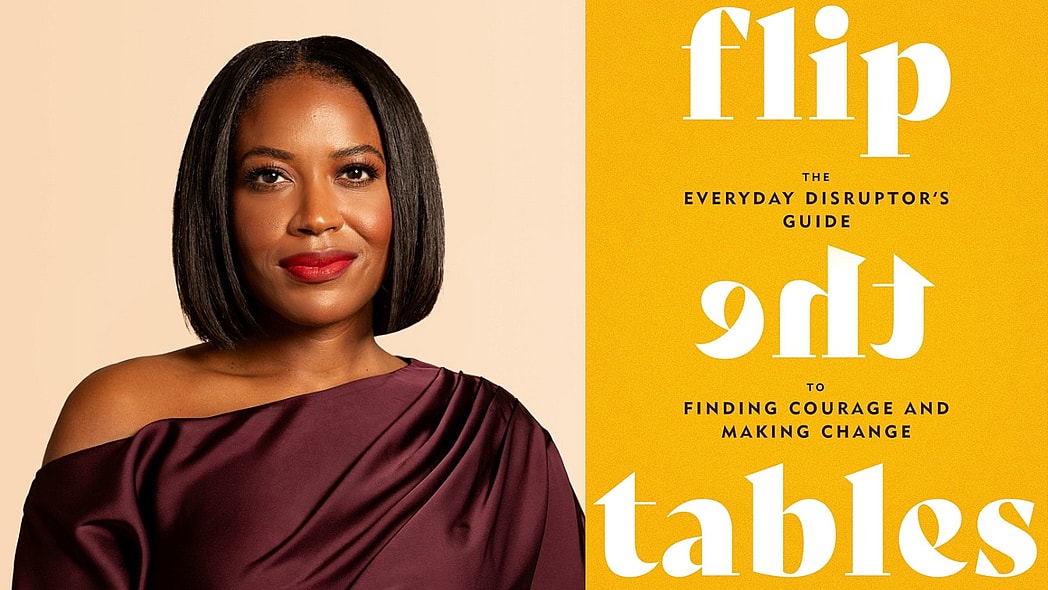

The excerpt below is from Alencia Johnson’s new book, “Flip The Tables: The Everyday Disrupter’s Guide.“

“Girl! I’m tired of doing all the things, the pressure of the world,” I exhaled during a catch-up with my friend Jess. We were sharing life goals, which for me was a chance to release the exhausting pressure of achieving and getting off that hamster wheel. “Forget this boss life!”

“That could actually be a whole book for you,” she replied. “Wait, what?”

“You’re kind of Black girl goals. For you to open up about how that isn’t fully serving you would be groundbreaking for so many of us,” she responded.

She saw me, she got me.

She freed me.

Let’s clear up one thing—there’s nothing wrong with Black girl magic. It encompasses the unique resilience, creativity, fortitude, strength, and beauty that Black women have. Our ability to make something out of nothing. To excel at multiple things at the same time.

Created by DC native CaShawn Thompson, the phrase is inherently ours—Black women, that is. It describes our unique existence and the ways we magically move through the world. Thompson has said the concept came to her as a child understanding womanhood. “I grew up in a family of women—not only women, but the women (of course, as we always are) were the movers and shakers of my family. What I knew of womanhood and girlhood was Black, and the work that I saw them do, to me, at four or five years old—I thought it was magic, because that was my point of reference. I was a huge fan of the fairy tales that my mother would read to us, so when I would see the women of my family in movement, doing everyday things, I literally thought we were magic.” (Newton, 2020)

Her description reminds me of Afrofuturism and how our existence alone, our birthright, and the way in which we move are truly magical.

When Serena Williams was faced with transphobic and misogynistic attacks in 2013, Thompson tweeted, “I don’t know what they’re talking about, but Black girls are magic.” It eventually turned into a hashtag without “are” because of Twitter’s character limits and took off.

A beautiful descriptor that so many Black women, including myself, embrace.

But as often happens, society has commodified (read: commercialized and monetized) the term, redefining something that was positive with negative tropes. And now #blackgirlmagic has become synonymous with the strong Black woman trope. A stereotype that robs Black girls of their youth through adultification. That tells us our pain is nonexistent or valid. That we do not deserve rest. That we should be grateful for crumbs.

And for that, I am tired. Black women are not here to save the world, to let go of the need to tend to ourselves. To push toward success alone while ignoring our inherent right to simply exist. To not hurt or feel pain.

Couple that with our uniquely marginalized experience at the intersection of our Blackness (racism) and our womanhood (misogyny)—called misogynoir—and we are seen as superhuman, devoid of humanity, facing a barrage of systemic harmful outcome…

It’s clear that Black feminist frameworks have helped masses of people who do not identify as Black women. And that’s fine. That’s what happens when we center marginalized experiences. I do, however, need people, in all of their gratitude and admiration for our magic, to stop asking us to save the day—run for president, lead an organization, et cetera—in institutions that do not support us. Well intentioned, yet harmful impact…

The societal pressure from capitalism forcing us to labor and produce more isn’t just harmful to women—the patriarchy doesn’t help men, either. It tells them that physical dominance, lack of emotion, and astronomical wealth make them worthy. It encourages men to ignore their emotions in favor of overcompensating at work…

Sure, I want to live comfortably without worrying about finances and leave a legacy for my children, their children, and the causes I support. Remember Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs? I desire freedom, health, security, and wholeness above all.

However, I gave myself the permission to define the grind differently for myself.

When society rewards achieving our dreams fast (hello, 30 Under 30 lists!) and lucrative (hey, person who sold a company for $500 million in just five years), it subconsciously tells us that we are not successful if we haven’t hit a professional milestone by a certain age or number. Couple that with the pressure to become married homeowners with kids by thirty—whew! No wonder death by suicide is rising among millennials, young women, and Black people. (In 2023 and 2024, mortgage rates were insanely high and economists agreed that for millennials and Gen Z, homeownership was not necessarily the wisest choice depending on your zip code.)…

While life’s responsibilities and the inequities that force many people to live paycheck-to-paycheck can cause our plates to feel full, there are still things within our control.

If our plate is always full, how will we have the room for the unexpected opportunities? The room to receive. The room to show up for ourselves. The room for God to use us in new ways. I don’t want to be in the business of missing a blessing or the opportunity to be a blessing to someone else because I was too busy.

Too busy to be still. Too busy to hear. Too busy to be used.

Busyness is a trap. The busier we are, the more we run from ourselves and our purpose. Sure, there are high-pressure times that require us to show up nonstop. That’s life.

However, I love that the pandemic made us realize that a booked and busy lifestyle wasn’t serving us. We’d been equating booked and busy with success when it was just burnout and unhealed trauma trying to survive under oppression and capitalism.

Everyone can take a break and quiet the noise of the world.

This rest disrupts grind culture and tears down how capitalism has us sick and isolated—and I love it. Matter of fact, I was trying to finish this chapter and felt myself dozing off. You know what I did? Shut my laptop and went to bed. You’re getting better words from my fresh brain now.

Excerpted from FLIP THE TABLES by Alencia Johnson. (Copyright 2025) Used with permission from Worthy Books, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.