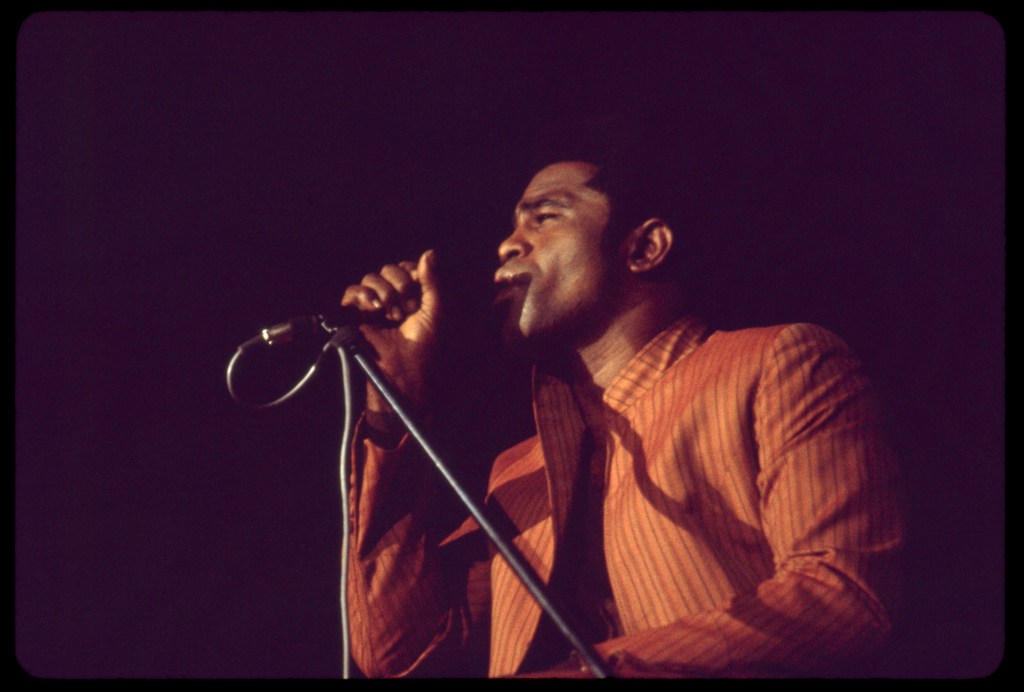

Cortney sits down with filmmaker Deborah Riley Draper to discuss her new documentary, James Brown: SAY IT LOUD. The pair speak about James Brown’s role in the Black Power Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, Brown’s iconic song “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud,” slavery’s influence on Black entertainment, the history of hip-hop, r&b, soul, and rock musicians sampling James Brown, and funk music’s impact on contemporary genres. Cortney and Deborah also have a nuanced conversation about how to discuss artists with complicated pasts.

Full Transcription Below:

Announcer: You are now listening to the Griot’s Black Podcast Network, Black Culture Amplified.

Cortney Wills: Hello and welcome to Acting Up, the podcast that dives deep into the world of TV and film that highlights our people, our culture, and our stories. I’m your host, Courtney Wills, entertainment director at The Griot, and today I’m joined by Deborah Riley Draper, the award winning and critically acclaimed filmmaker who is responsible for Much anticipated project, James Brown’s Say It Loud.

It debuts on a two night premiere event February 19th on the A& E network, and she directed and co wrote this four part documentary series, executive produced by Mick Jagger and Amir Questlove Thompson. The docuseries examines Brown’s legacy through exclusive interviews, never before seen footage, and his beloved music catalog.

Documentary Trailer: Hit it! Everybody wasn’t that talented. Everybody wasn’t exactly as driven, that maniacal drive. It’s hard for me to think about my dad as the most important black man in America. Because he was my dad.

You’re probably already familiar with the work of Deborah Riley Draper, who co wrote and directed this new project about James Brown. Her two part series, The Legacy of Black Wall Street, was on OWN. I think she got an Image Award nomination for that one. And she was also behind Olympic Pride American Prejudice, which is this incredible documentary that she directed, produced and wrote that tells the story of the 18 black athletes who went to the Olympics in 1936.

While Hitler was running amok in Germany and, you know, the Jim Crow South was in full effect here. That film won a ton of awards and is so good. She is someone that I’ve wanted to interview for so long and I’m so grateful that she decided to join us on Acting Up today. Hi, Debra.

Deborah Riley Draper: Hi, how are you? Thank you so much for having me on your amazing podcast.

Honored to be here and so grateful to talk about James Brown’s Say It Loud.

Cortney Wills: When I tell you that I learned so much about James Brown through watching this, it was like every part. But even better, and it made me realize how necessary this project is because someone like me who, you know, I pride myself in knowing a lot about music knowing a lot about entertainment.

Of course I know about James Brown but I had a very specific idea of who he was. And absolutely no grasp of the actual impact that he had on the culture, on the country, throughout his, what, four decade career?

Deborah Riley Draper: Absolutely. The framework for this documentary started when I was doing my research and I watched hundreds upon hundreds of interviews and listened to the music, but I stumbled across the cover.

Of a 1969 look magazine. And on the cover of the magazine, it said, is James Brown the most important black man in America? And I was like, wait, what? This is the cover of this magazine. And that question became the framework of the four episodes that you watched, because I wanted to understand. That question, I wanted to understand the answer, but I wanted to create a canvas that James Brown could participate in the answering of that question directly, because there were so many lessons in his interviews, so many things he said on stage, and even on kind of the records when he’s in the studio, and the engineer is still recording, and he’s talking to Bootsy, or he’s talking to Sid Nathan, or he’s talking to the band, So all of this helped me answer that question, but I knew James Brown through my mother, through my father, through my uncles, but what I had missed Was James Brown and his commitment to blackness.

I miss James Brown as being this fundamental figure and understanding black history and the lived black experience, right? Born in South Carolina, abandoned by his parents, seventh grade education in a juvenile institution. So he’s poor, he’s black, he’s from the South, he’s undereducated. And then he has the resilience and the creative genius to build what we know to be James Brown.

It’s a phenomenal story. And at no point in those four to five decades of James Brown as a cultural, political, social, and musical figure did he ever not be Black. It does, he didn’t code switch. He was Black on Black on Black on Black every single day, period. Whether he was sitting in the dressing room, In his pink curlers or if he was dancing and he emoted that pain, that joy, that triumph that connected us back to our history, back to our ancestors.

And, and that, and that’s what I wanted people to get when they watch this.

Cortney Wills: That is exactly what I got, Debra. You hit it right on the head. I mean, I’m glad that you said, you know, what you knew of James Brown first, from your parents, from your uncles. Because that was my question, like, how did you come to this?

Because I know how I came to it. And it’s like, yes, music legend, number one, I’ve never seen him so much and so close. All of that footage, all of those interviews that you just spoke about. We see closeups, we see like what he looked like young, his body, his face, like, you know, where he was handsome, where he got really puffy, like it was just this whole trajectory of images that even though I’ve known this name, I actually never had so much content to look at from him.

And so that was really interesting for me. And the other part. Was exactly what you just said, like really putting together, not only what he did, but the time at which he was doing it is what made it, I mean, revolutionary is an understatement. It was so provocative. It was so almost unthinkable what he was able to do and to achieve.

And then so much of it was absolutely an unapologetically black, like godfather of. Really, I think black pride and there you go with his song, you know, I’m black and I’m proud, but he was the epitome of that.

Deborah Riley Draper: He was, he understood that the culture and the community needed the injection. And he knew that our record.

could be the thing that helped us understand. And in completing the four episodes, I stepped back and I finally understood the song, Say It Loud.

Of course, I knew the words, you know, Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud. But I understood, say it. Loud. Yeah. Because what that meant was for so many centuries as black people, we had to self silence. We had to be quiet. We couldn’t speak our truth. So James understood, say it. And you needed to say it because it can be erased.

It can be hidden. It could be discarded. It could be swept under the rug. And you had to say it loudly because you need to say it loud enough for the ancestors to hear and the future generations to hear so that we could all be connected to the blackness and be proud of it. And that was a very powerful thing to do.

It was liberating to understand it. It’s liberating to hear it. And it’s also liberating to know that that was a moment in time that changed us. It was a moment in time that we needed someone to tell us in our grief, post assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, in our bewilderment, in our not understanding our footing and our place in this country, for someone to tell us, say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud.

That was the anti blackness antidote that we need then and that we need now, straight up.

Cortney Wills: Absolutely. Absolutely. And at the same time, I mean, the way that you broke this up, uh, in four parts, I think was really smart. It was really necessary because Again, you know, you, the big picture, the whole picture of James Brown is not entirely cohesive, you know, and if you just hear bits and pieces, like I did, I think growing up, you might have a really, you know, what you think is knowledgeable opinion about him and be missing a whole entire.

Very important part. And of course, what I’m talking about is, you know, what I know about James Brown is he was great. The soul singer, one uncle of mine is just obsessed. I mean, you cannot say one thing against James Brown. He will fight anybody who is ready to talk about him. But I mean, I, I think I came up more when he was a bit of a reference and a joke.

And, um, you know, somebody that Eddie Murphy was impersonating or someone that I saw in the blues brothers, he was a character. You know, with the Motown and with, you know, those older, you know, classic singers, he was a figure, but this project really humanizes him, um, piece by piece from his childhood and what was going on in the world and in the country and in his town, um, what was going on in his home, what was going in his mind, and then we get This art birthed from so much pain, but also what I thought was so interesting was how it was inspired and taken from, oh gosh, you, you named it in the documentary, but it’s like a kind of dancing, you know, it’s not like tapping, but moving the bottom of your body and

Deborah Riley Draper: buck dancing.

Yes. Buck dance. was the dance that enslaved people did to entertain white people. Yes. It’s resistance, right? I’m, I’m using my body to save myself and to preserve my life to entertain you so I can take the emphasis off of you trying to get rid of me. That part.

Cortney Wills: But that’s not what I thought it, you know, shucking and jiving is what I would have said.

Somebody would have said James Brown would do. And that same kind of historical relation, same use could be thought about like something that we should be, you know, embarrassed about or shouldn’t do. But in this film, the way that we were able to see the historical context from slavery time, you And James Brown even being savvy enough to recognize that he could pay his family’s rent dancing like that for white people down the street as a child.

It was, it was, as a child, he was taking the power back and using it and monetizing.

Deborah Riley Draper: He was surviving. Yes. That’s what I wanted us to understand the shucking and the jiving and the buck dancing that survival and it’s also resistance Yeah, it’s it’s I am going to exist and I’m going to survive in spite of these circumstances so we actually should reclaim that history differently and Understand that the way our ancestors had to live The way they had to move, the way they had to navigate the country required them to, to move in ways that we might consider shameful, but it wasn’t.

It was strong, it was powerful, it was a method of surviving, and it was also a method of revolutionary existence. Because I’m gonna take care of my family with these quarters, with these nickels, with these dimes. I’m gonna pay my rent. But that was the training ground for him to become he’s working hard at eight and nine years old, but that’s the work ethic that became the hardest working man in show business.

The man that could do two, three, four hour shows, you know, at a time.

Cortney Wills: Yes. Yes. And then the sound, I mean, just really recognizing that he absolutely. Created and cultivated. What is the basic, the basis of all of our music. In the documentary, we learn that James Brown, who hated, hated being sampled so much, has been sampled 15, on over 15 times.

What really blew my mind is that Janet Jackson’s iconic song, That’s The Way Love Goes, is actually a James Brown sample.

Here’s James,

and here’s Janet.

Like, what? Like, every single one of your favorite songs, OG hip hop tracks. Like those were all James Brown samples.

His 1970 hit funky drummer has been sampled so many times from the likes of Dr. Dre to Nas to Public Enemy, Let Me Ride, Get Down, Fight The Power, all borrowed sounds from that record. Not just soul hip hop. I mean, everything. It’s like, wow, that is.

Deborah Riley Draper: And it included George Michael, Sinead O’Connor, Ed Sheeran. Um, when he invented funk, he changed music. And that sound, that impacted Parliament, Bootsy Collins, Prince. That impacted Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson. So, Our musical repertoire, as we know it, like the things we claim, there’s a fixed line right back to James Brown.

So for me, that’s what was important to sit down with LL Cool J, to sit down with Chuck D, to sit down with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. And trust me, when they talked about that’s the way love goes, I hit the floor. I’m like, what? I did not know that. And that’s one of my all time favorite songs ever, right?

Ever. And I’m like, what? Yes. Oh man. And talking to Questlove, he always, if he’s looking for something, if he’s looking for inspiration, or if he has a question, he plays James Brown and he gets the answer. Come on.

Cortney Wills: You know, it was really interesting. You just brought up Quest and that made me think about something I was definitely grappling with in the first episode.

And then it just kind of dropped, but that was. I mean, I think I came to this project with a bit of an attitude, like a bit of a chip on my shoulder. And with any documentary, especially about such a famous person, you always wonder what the intent is, you know, who’s telling this story, and we saw.

Journalists, we saw, you know, his backup singers, his band members, we saw his daughters, like a lot of really varied perspectives. Uh, Reverend Al Sharpton was a huge part of this documentary and everyone that you picked spoke about him really irreverently. And at first it felt like, God, is this going to be like an apologetic, we’re apologizing for him being an abuser kind of.

Story and perspective and what really develops over the course of this docuseries is not that every single person that was there speaking about him really acknowledged, um, and really came from a place of, I think, maybe acceptance of the fact that this is a very complicated. Person like two things, three things, 10 things can be in were true at once about James Brown, and people didn’t make apologies for that.

They also didn’t let that succeed at wiping out the contributions. And I felt like that was so important and I came away from this with a different kind of respect and a different kind of understanding of James Brown. Um, and I think so many people will too, but what I wondered is whether or not we will be able to apply that kind of lens to people that we find problematic now.

You know, like this, I, my kids are seven and eight and I have one year olds, but, um, the babies watch Motown magic, which is this like animated Netflix show and, um, Smokey Robinson. And I think Westlove are producers. So they have the real music. So my kids are walking around the house, singing Supreme, singing Jackson five.

They’re being exposed to all of this music. And, you know, like any other living, breathing human, once you get bit by the Michael Jackson bug, you go down a rabbit hole. So they are deep into MJ discovery. And I, as a parent, am like, what are, like, let me check the winds. Like, what are we doing? Like, how are we handling Michael Jackson in 2024?

Right. And so we were faced with that all the time, whether you’re talking about Dr. Dre or, I mean, so many people, so many people who are dichotomous at, at least, it’s often hard to get around that and to understand Whether or not we should or we could separate the person from the art or the less than desirable traits with the impact and the benefits to our community.

And so I wondered if you grappled with any of that, either before you took on the project or once you actually were in it and. Learning all of these truths, um, and deciding how, how to balance them. How do you go about that, especially now?

Deborah Riley Draper: You know, my second documentary was Olympic Pride, American Prejudice, the story of the 18 African American athletes who faced Hitler and Jim Crow at the exact same time.

Cortney Wills: So good if you haven’t seen it, please. It’s amazing, you’ve got to watch that one too. Sorry, go ahead, Debra.

Deborah Riley Draper: No, thank you. But think about these. Athletes, 17 and 18 years old, and they had to grapple with an America that treated them as second class citizens, but also wear USA on their back in Nazi Germany and compete and run and win medals for a nation that did not accept them.

So when we look at a lived experience of a black man or any man, we have to look at it holistically and I approached it without judgment. I approached it with here’s a life. A life lived, a life that had high highs, low lows, ups and downs, a life that had resilience, a life that had trauma, a life that had pain, a life that had success, a life that had failures.

He’s a flawed, imperfect, creative genius with demons on his shoulder.

Cortney Wills: That part, yes. And you know what else I think was a little bit, I don’t know, it just helped, I think, uh, was his daughters and his son being a part of it because they really Same thing. They’re, they’re so enamored with their dad. They’re so proud of him.

They were so present and they’re honest. Yeah. They were so present for so much and so many of his wins, but also his losses and also his lows. And, you know, there are times where you’re looking at these girls and you’re like, wow, like you’ve really been. Through some trauma, but I think it’s also clear that they’ve done some work and that there have been evolutions of how they look at their dad and what they believe about their dad, and they’re not offering excuses for his behaviors, but absolute explanations.

And again, contextualizing the time that James Brown was alive and doing this and making these choices. And how drastically this country changed within those 40 or 50 years, it’s almost hard to even grasp. And so, the same way that we can look at things like the color purple and through a different lens and the way that we look at them now, this is the time that we’re talking about, I mean, two generations removed from slavery.

Um, the trauma of Black men, you think that James Brown was troubled, what do you think his father was going through? Or the person who raised that man, you know, what did love look like? Love meant keeping your ass alive, period. That’s it. That’s actually, and keeping my ass alive, hopefully, like that’s absolutely.

And so watching his daughters be able to come to an acceptance and an understanding about Maybe why he did some of the things that he did, I think was really comforting. And it was also kind of a lesson in. What the possibilities and healing could be and also how healing it could be to to do exactly what you did in this documentary, which is tell stories that examine what was happening through the lens of our history, because then things start to make sense.

And it was not all doom and gloom, but it was not all always perfect. And like you said, like, whose life isn’t actually. Like that, who can’t relate to that. But I didn’t realize what an actual rockstar this man was essentially later in his life.

Deborah Riley Draper: Rockstar. Okay. Come on.

Cortney Wills: And then you’ve got Mick Jagger, which was like, so cool.

Tell me what you did. Tell me what you were doing in the room when Mick Jagger said something like. Oh, yeah, and I think he had like a little bit of a drug problem or something, but

Deborah Riley Draper: like, who didn’t, you know, I’m trying to be super cool because it’s Mick Jagger, right? And with all of the interviews, but Mick in particular, because not only was I interviewing him, he’s also the EP.

So I, you know, he’s, he’s talent and the executive producer. And a very well documented and thoughtful music historian on top of that. So his knowledge is deep and broad about music and about James Brown in particular. And when he looks at music, he looks at what music does for people. The audience, but also what music can do to someone who gives everything every part of their soul to the audience and they leave nothing on the table.

He’s clear about what was happening in the 70s, how disco was coming and drugs were coming in and everyone was experimenting and trying to be like James Brown, including James Brown. I think. What’s interesting for me was listening. And that’s how you, you talked about how I approached it. Listening was a big part of that.

I wanted to listen to everyone I interviewed, um, because in those interviews, they shared why James Brown inspired them, but they also shared and helped Textualize the time, like when Mick Jagger and the Stones were on the Tammy show in the 60s, when James Brown is literally kind of integrating America’s living room,

because they hadn’t seen a black man move like that, you know. in those spaces ever before and talking about that relationship with Sid Nathan, who thought it was okay to be in a recording session and tell James Brown how to sing. You know, so you get to see the dynamics of what James Brown, even as a remarkable talent, had to deal with as a Black man in the recording.

He still had to engage with people who felt that they were powerful enough to tell him how to do his craft, and he’s the best in the game. So I, I wanted it to be a lesson about our country seen through the experiences of James Brown. I wanted us to understand what it’s like to be a Black man growing up in the Depression, buck dancing during World War II, cutting his first record in the fifties, when America’s in this post, you know, World War II industrial revolution, and, and suburbia is having this Wonderful, amazing growth across the country, and he’s hustling in this chitlin circuit, trying to make his bones, trying to make a name for himself, working night and day, um, trying to create.

Yeah. And survive. Yes. And be the best. Work hard at it. Um, James Brown is about resilience. It’s about work ethic. It’s about understanding your God given talent, your creative genius, and sharing it. He shared when you listen, and I listened every Friday with Harry Wanger from UMG, from Universal. He would play me music every Friday at three o’clock for like 10 straight weeks.

And we listened. And you can hear, if you just listen, you hear the testimony, you hear his lived experience. And he’s telling you his story. He mentions being a shoeshine boy in so many songs. He mentions Augusta, Georgia in so many songs. He mentions not wanting to die without power in so many songs. Self empowerment.

Don’t be a dropout, right? Mm hmm. He’s telling us all these things that we need to know as a culture so that we can be better, stronger, more impactful, own our power, and essentially liberate. You’re so James Brown may not have been able to liberate himself, but he certainly liberated us and he created a framework and a foundation for us to take music business by storm.

Cortney Wills: Yes, yes, Deborah I am so bummed I have to let you go because I have a billion more questions for you but my final one is, if you had one more segment, like one more hour what did we not. Get what story? Did you not get to tell us? What did you hate to leave on that cutting

Deborah Riley Draper: room floor? I think if I had one more episode, I would actually talk about the influence of style and fashion and the entrepreneurship just a little bit more that if you look at James, you mentioned being able to see his face and his body and his clothing choices.

I think that really speaks to his trajectory and his blackness. Across his seven decades on this planet. It spoke to his liberation and his freedom. It had also spoke to all of the black people he engaged in the hair and in the clothes and in the telling of his story through fashion and style, because so many times we are able to communicate our history and communicate our emotions through hair, through clothes, through rings, through jewelry. And I think that was really an important part of him. And I think that’s why my uncles and my father and the Black men in my family really responded to him. Because he was able to do and say things that they couldn’t, but that they wanted to. That was something that they looked up to him for being able to have a certain level of freedom to be able to move around this country and move around this world and go places and be places that they probably wanted to go in and be too.

And he did that for them. Yes, he did.

Cortney Wills: And thank goodness that he did. Thank goodness that you made this incredible project. Say it loud. Everyone, please go check it out. It starts on A& E, two night premiere event starts February 19th. That’s a Monday. Deborah, what a true honor. What a treat this conversation was.

I am such a big fan. And so grateful you

Deborah Riley Draper: took the time to talk to me today. Thank you so very much. Hopefully I’ll be back to talk to you soon, but I truly enjoy the work that you do. Congratulations on everything. Thank you for supporting all of us creatives. We love it. Thank you so much. You take care.

You too.

Cortney Wills: Bye bye.

Music Courtesy of: Transitions Music Corporation, Black Ice Publishing, Reach Global Songs

Media Clips Courtesy of: A + E Networks

Acting Up is all about Black Hollywood, who’s making noise, who’s making a difference, and how they’re moving the needle regarding representation.

Cortney Wills has forged deep connections with creatives, actors, directors, producers, writers, executives, and the real decision-makers who shape how our community is represented onscreen, giving Acting Up access to the inner workings of Hollywood.