The ultimate Black history lesson with Secretary Lonnie Bunch

Episode 52Play

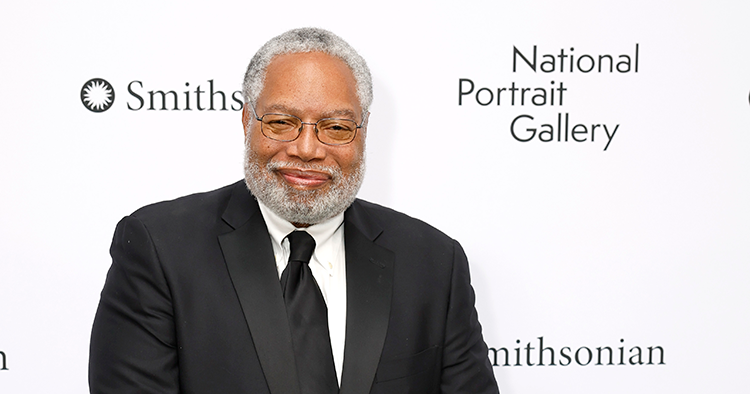

Legendary historian and the first Black secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Lonnie Bunch, joins The Blackest Questions for an intimate one-on-one discussion about some of the country’s forgotten Black historical figures. Bunch talks about his heroes and gets candid about what needs to change in museum leadership across the board. He also describes the hurdles and setbacks of opening the National Museum of African American History and Culture. He explains what it was like to be an integral part of such a significant project.

READ FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Panama Jackson: [00:00:00] You are now listening to theGrio’s Black Podcast Network, Black Culture Amplified.

Dr. Christina Greer: Hi, and welcome to the Blackest Questions. A trivia game show meant to teach us more about Black history. I’m your host, Dr. Christina Greer, Politics Editor for theGrio, and currently a Moynihan Public Scholars fellow at the City College in New York.

In this podcast, we ask our guest five of the Blackest questions. So we can learn a little bit more about them and have some fun while we’re doing it. We’re also going to learn a lot about Black history, past and present. So here’s how it works. We’ve got five rounds of questions about us. Black history, the entire diaspora, current events, you name it.

And with each round, the questions get a little tougher and the guest has 10 seconds to answer. If they answer correctly, they’ll receive one symbolic Black fist and hear this. And if they get it wrong, they’ll hear this. But we still love them anyway. And after the five trivia questions, there will be a Black bonus round, just for fun, and I like to call it Black Lightning.

Our guest for this episode is [00:01:00] educator and historian Lonnie Bunch, who’s a history maker himself. He’s the first Black person and first historian to serve as the head of the Smithsonian in its 177 year history. Lonnie has curated collections from some of the nation’s top institutions, including the California African American Museum and the Chicago History Museum.

And he was instrumental in the creation of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D. C., serving as its founding director. And he is currently the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. I am beyond excited to have you here. We’ve never had a historian on the show.

Our listeners are in for a real treat. Thank you so much, Lonnie, for joining The Blackest Questions. Are you ready to play?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: I am so excited. But now you put all this pressure as a historian. God, I… I gotta, I gotta represent.

Dr. Christina Greer: Well, and here’s the thing. And we tell all of our guests this, we are here to have fun.

Black history is American history, as you very well know. And we want to make [00:02:00] sure our listeners go beyond Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, who were great, but there’s so many Black people, institutions, and events that we should know about. Um, and our listeners should know about to help them make sense of the world.

So. We’re going to start with question number one. No pressure. You know, you’re just the 14th secretary. That’s all. We’re waiting for that portrait on the wall. Okay. Are you ready to play?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Yes.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. In May of 1963, thousands of children bravely protested segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. Some of them, as young as four years old, marched for days despite being met with hostile tactics from authorities with high pressure fire hoses and police dogs.

Can you name this pivotal event in the Civil Rights Movement?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: This is the Children’s March as part of the Birmingham March of Martin Luther King. And I know it so well because my wife was one of those children walking in Birmingham in 1963.

Dr. Christina Greer: Oh my goodness. Well, you are absolutely correct. The [00:03:00] Children’s March, also known as the Children’s Crusade, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led protests in Birmingham just weeks before the children got involved and he was arrested and penned his powerful, Letter from Birmingham Jail. The children were trained in the tactics of non violence and on May 2nd, 1963, they left in groups from the 16th Street Baptist Church.

The protests lasted several days and hundreds of children were arrested, causing outrage around the world, which forced city leaders to agree to desegregate businesses and free everyone who was still sitting in jail. The Children’s Crusade was considered a success and even compelled President John F. Kennedy to publicly support federal civil rights legislation.

However, four months later, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four Black teenage girls and injuring 20 other people. And so I know in the last couple of years, we’ve heard a lot of talk about a third era of reconstruction and what these changes mean in our country. Bonnie, historically, do you believe we’re heading in that direction or do you think we’re already in a certain [00:04:00] reconstruction in our nation?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Well, I think that what we realize is reconstruction never ends. So whether it’s the first, second, or third, that the struggle for fairness, the struggle for racial justice, um, is really an ongoing struggle. So my notion is that we are at a point where we have to sort of reignite the movement. We have to regenerate and generate ourselves because in essence, what’s important is that this is something that we have to realize that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance and the price of freedom is eternal protest.

Dr. Christina Greer: The price of liberty is eternal vigilance. I have, I don’t have any tattoos, Lonnie, but I think you’ve just given me my first tattoo. Um, and so, I mean, you know, obviously your wife is, is a civil rights figure that we can now put in our hearts and on the pantheon of people who have made this country so much better and safer for Black people.

As a historian and all the work and research you went through [00:05:00] in preparing this museum for us and for the world, do you have a favorite Black figure in history? Like, do you, is there someone that you go to, you know, for me as an educator, I always look at Mary McLeod Bethune. She’s kind of one of my favorites.

It’s a Black woman, you know, she has roots in Florida, just like, uh, you know, my relatives. Do you have someone that, you know, you read up on when you need either inspiration or just, uh, you’re having one of those days that you need a little clarity?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: You know, while I have a lot of people whose names people know, it’s really those that one doesn’t know.

In my office, I have a picture of a Black woman who was enslaved. It’s probably taken two years after the, after the Emancipation Proclamation, and she is this small woman carrying a hoe that is longer than her, a heavy basket, her knuckles are swollen from work, her clothes are tattered. But her head is up and she’s stepping forward.

So she inspires me every time I thought I couldn’t build the museum or [00:06:00] these folks were driving me crazy. I’d look at her and say, she didn’t quit. I can’t quit. So it’s those kinds of folks whose names we don’t know who are famous only to their family, who really inspire me.

Dr. Christina Greer: I love that. I mean, I really hope you know, the point of this podcast is that people will be inspired to do a little more research.

Um, nothing makes me happier when I get a text from someone or a DM that says, you know, I got zero out of five, you know, like I knew nothing that was going on. And I’m so sure that in the museum people go in and they’re discovering someone new, which leads them to do even more discovery. Um, and so, uh, I’m so excited you’re here.

Are we ready for question number two?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: I am always ready.

Dr. Christina Greer: You’re listen, you’re one for one. So let’s, let’s keep it going. Okay. Question number two. After the Civil War, the Wild West was appealing to Blacks who were hoping for freedom and fair wages. And despite what’s portrayed in books and movies, it’s estimated 25 [00:07:00] percent of all cowboys were Black.

In fact, one of the most famous cowboy characters depicted on television and in movies is believed to be based on the life of a real cow, a real Black cowboy. Who was this famous cowboy?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Marshall Bass.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. A. K. A.

The Lone

Ranger.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: I was just going to say the Lone Ranger.

Dr. Christina Greer: Marshall Bass, Bass Reeves. So also known as the Lone Ranger for our listeners out there who either watched it or like me watched it when they went to visit their grandparents. And my grandfather always had the Lone Ranger on. The Lone Ranger began as a radio show in 1933 and had more than 1300 episodes before becoming a popular television show in 1949. The Lone Ranger character, who is a masked former Texas Ranger fighting outlaws, was played by a white man, but the character was actually inspired by a Black man, Bass Reeves. Reeves was born enslaved in Arkansas, but escaped during the Civil War and lived in Indian Territory. He eventually became a deputy U.S. [00:08:00] Marshal who arrested more than 3,000 people and had a Native American companion that traveled with him, just like Hollywood portrayed. Black cowboys were typically responsible for the toughest jobs like breaking horses and being the first to cross flooded streams during cattle drives. It’s believed the term cowboy originated as a derogatory term used to describe Black cowhands.

So can you share some other roles in history that Black people have held that are possibly often forgotten or overlooked?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Well, I think the notion of the Black west. It’s not just the cowboys. It’s the settlers on the plains. It’s those that go to Los Angeles or San Francisco or Denver, so that the West is really this opportunity for African Americans to escape the violence of the South.

And also to go place where there’s more land. So what you see are farmers and pioneers, um, in the West that are really very powerful. The other thing for me is that I think [00:09:00] the most important aspect of what people undervalue of Black life, are Black teachers. You see all of these educators who go into the South during, after the Civil War to create freedom schools.

You see people like, people like Mary McLeod Bethune recognizing that it’s really important to have universities and that in essence, I think that the great, um, group that needs to be celebrated are Black teachers, historic, and those Black teachers who were in segregated schools who many lost their jobs when integration came.

So they are really the people who believed that African Americans should be educated and through that education could have doors of opportunity. So I always celebrate the historic teachers and the contemporary teachers.

Dr. Christina Greer: Oh, wow. And didn’t Nell Painter write a book about Exodusters?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Called The Exodusters. which is about the movement of people from Louisiana to Kansas. Um, and I think what Nell [00:10:00] did in her book was help us rethink that the migration of Blacks didn’t just go to Newark, New York, Detroit, um, but that they went to Kansas and went to Denver and to Los Angeles. And so I think that what’s important is to realize that Black people touched everywhere. Black people were really driven by the, by the desire for opportunity, for freedom, for access, and a way to protect their family.

And for many, going West was just that.

Dr. Christina Greer: Absolutely. I mean, I was just in Alaska, Lonnie, and it made me think about my aunt, who’s my aunt by marriage, um, who’s in her early 90s. But she and her family, were on their way to Alaska, got to Seattle a day late, missed the boat and then her aunt set up a hair salon, which became a very successful hair salon while they were waiting for the next boat to come.

And they ended up living in Seattle. So Seattle even has a historic Black population as does Alaska, which, I mean, I’m [00:11:00] fascinated where, you know, or Eddie Murphy had the joke, like, you know, Black folks are only in like, you know, 10 cities that James Brown shouts out. Yes and no. We’re everywhere.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Absolutely.

I mean, I think that, you know, for me, my dad used to talk about he wanted to always go on the Alaska Canada highway, right? That was something that was important to him. And so when I went to Alaska, I did that because I realized that Black folks built it. Black folks were part of it. And so, in essence, what you do is you’re always wonderful when you go someplace like I’m in Alaska and I see all these Black people.

And so I realized that we go where the opportunities are. We go where we can take care of families. We go where we can find fairness.

Dr. Christina Greer: I remember going to high school in Illinois and, you know, my parents are asking me, how’s everything going? And I, and I say, Illinois, because it wasn’t Chicago. It was an hour North, closer to the Wisconsin border, about 10 minutes away.

And I said, well, I mean, it’s fine. But all the Black people are so country up here. And what, what I think I was tapping into was [00:12:00] this kind of second and third generation, Mississippi, Alabama, that I, you know, I knew about the great migration, obviously, but sort of beyond Chicago, going up towards Wisconsin and this idea that, you know, where there’s movement, you will find Black people.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: That’s right. Um, and where you’ll find Black people is everywhere where they think they can find hope and fairness. That’s what you see. And so I love the fact that I’ve always argued that you scratch a Black person, regardless of where they are, and they’re a generation or two from Mississippi or Alabama.

So that’s right. So we are a people of migration, but we’re also shaped by our southern roots.

Dr. Christina Greer: Mm hmm. Okay. Um, we’re two for two. Are you ready for question number three, Mr. Lonnie Bunch?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Oh, I’m getting nervous, but I’m trying.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. Back in 2011, more than 30 boxes of Tupac Shakur’s personal items were put on display in one of the few publicly available [00:13:00] research collections of an individual hip hop artist.

The collection includes handwritten manuscripts, diaries, song lyrics, and more. Where is this collection housed?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Okay, that’s a hard one. Um, can I get a couple of guesses? UMass? Or the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Dr. Christina Greer: Rick, we need to go to the South.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Oh. Okay, you’ve got me on this one.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. Can’t believe we stumped Lonnie Bunch. The Atlanta University Center, Robert W. Woodruff Library. So, it took two years for the collection to be categorized, which covers 1969 to 2008. The collection was gifted to the AUC Woodruff Library by Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur, who is a political activist and member of the Black Panther Party. She said that Tupac, who was murdered in 1996, loved the city of Atlanta, and she wanted his work to be explored by academics in hopes that more institutions would create courses devoted to hip hop.

And in [00:14:00] 2017, access to the collection became limited, but there are still dozens of videos and resources available in the library’s digital catalog. So! Let’s talk a little bit about museums. Something tells me you know a teeny bit about museums and how you come in position of these artifacts because, you know, the process can be very controversial when you’re, uh, amassing such a collection.

How do you all go about obtaining pieces and what happens when some of these pieces are requested to be returned. And I asked because I was a classics minor in college and I studied the Elgin marbles. Um, and that was, you know, large part of my research. And it was, we see a lot of the conversations are about the British museum giving back their artifacts.

You know, Greece is asking for their artifacts back from all types of institutions across the globe, but a little more locally in America, we’re having these conversations as well, not just personal artifacts, but obviously even human remains.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Well, you’ve raised so many issues. The [00:15:00] first of all, I think what’s important to realize is how valuable libraries are, that what was happening in Atlanta was also happening in Chicago, and what was happening in Los Angeles, that many people, Black men and women, realize how important it was to document that history by creating these libraries, which then allow us to do the research that scholars live on.

Museums, by their very definition are places that help us remember and that what they have in their collections are the way we remember. So things that aren’t there mean many communities are left out. When I was building the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I realized that it was really important to build collections.

But to not just sort of say, all right, what can we get, but rather go around the country and ask people to bring out their material, ask people to share their stories so that we could find Harriet Tubman’s hymnal, or Chuck Berry’s guitar, or really a hoe carried [00:16:00] by a sharecropper, um, that meant so much to his family.

So that the goal was to collect objects that people wanted to share and to tell stories of people who were well known and people who no one knew about it all. But I think the, the bigger notion you raised is who gets to control what’s in a museum. Um, and I would argue that part of what I’ve tried to do at the Smithsonian is say that while we’re a leader in scholarship.

And in collections and in museums. I want us to be a leader in ethical behavior. So I sort of helped the Smithsonian return bronzes to the knee because I think that it’s crucial for museums to look and say, how do we acquire this? Did we acquired ethically? Are there places they should that they should be returned?

So I’m a big believer of challenging museums around the world to look to your obligation. And the obligation isn’t just to preserve [00:17:00] material. It’s an obligation is to lead, is to demonstrate that through the stories you collect and the way you collect, you want to inspire people to live their lives that way.

So I’m a big believer in, um, returning materials, um, that are appropriate, that, that have been acquired in an appropriate way, um, back to the original place.

Dr. Christina Greer: Right. And I think what makes The African American Museum, or as people like to call it, the Blacksonian, such, such a powerful institution. And the reason why, you know, I’m such a fangirl and so many people are such fans of you as an individual and a leader is because you made sure that we had these iconic, uh, artifacts in the museum, but also artifacts from everyday people. I think that really makes the story come alive of Blackness because not everyone is Chuck Berry’s guitar, but also the history of sort of how [00:18:00] music led to freedom and to hope and to faith and using artifacts to tell that larger story.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: I think that’s absolutely right.

I mean, I think the goal for me was, first of all, create a museum that humanized history. That you didn’t think about slavery or migration, but you saw it through the lens of my grandparents or of an enslaved person, so that you cared about that. And everything through the museum, whether the size of the images we use, was to really have you react to other humans.

Not to figures that weren’t, that are long gone, but figures whose life shaped you. Um, going forward and the other thing was to recognize that these stories are deeply Black, but they’re deeply American and that these stories shape us all regards who they are. I mean, think about it when we think about education is the newly and freed who want education in the south and because of their desire suddenly, there’s public education in the south. Now it’s segregated, but the [00:19:00] reality is everybody benefits from the actions of Black folks, because in many ways, what the museum suggests is that it is the Black community that challenges that demands that helps America live up to its stated ideals. The, so almost every time when you see expansions of freedom, when you see the openness of citizenship, it’s tied to African Americans demanding fairness, not just for themselves, but for everybody.

Dr. Christina Greer: But for everyone. I mean, I think that’s the piece where so many people. So many immigrant communities have come to this nation in the last century do owe a debt of gratitude to the experience of Black people who have literally, uh, tilled the soil. And I think the museum really articulates that in a visual way for people to better understand that. I mean, I just, I’m such a fan. I can’t even, I can’t even go into it. I do want to ask you a little [00:20:00] bit more though, about the leadership of these museums, because we know that following the death of George Floyd, the country went through, you know, what they called the racial reckoning that affected so many different aspects of people’s lives, obviously, including museums.

And so many institutions were called out though, for the lack of inclusion, not necessarily just in the art that was displayed, but also in how the museums were staffed and governed. What’s your take on that situation? Have you seen any substantive change in the last few years about the leadership levels of museums in this post Reckon, post Reckoning era?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: You know, I wrote an article years ago And said that Black people in museums were like flies in the buttermilk, very few people and that, in essence, I would argue that over the last 20 years, museums have expanded, um, who they serve and who works in museums, but I would argue that the leadership is still awash with whiteness.

Um, and that, in essence, what I think has happened as a result of George Floyd’s murder [00:21:00] has been that museums recognize that they have to be part of a solution, that they can’t be community centers, but they could be at the center of their community and that, in essence, what I think is happening is that you’re now seeing more and more people beginning to rise into leadership positions.

Um, I see people running art museums now that are getting their opportunity. So I think that, um, it’s been a long struggle, and I think that there have been people who have really pioneered and open doors. Um, and that now you’re seeing the fruits of those doors being open, but I know, for example, I’m standing on the shoulders of people like John Canard or Rowena Stewart, who created museums in, you know, Chicago, New York and L.A And I’m hoping that the work that I’ve done through my career inspires, but most importantly, challenges people to work in museums and challenges museums to [00:22:00] recognize that they have to be as much about today and tomorrow as they were about yesterday.

Dr. Christina Greer: Absolutely. I’m sitting here talking to Mr. Lonnie Bunch.

It’s time for a quick break and a reminder to like and subscribe to The Blackest Questions and follow us on YouTube so you never miss an episode. We’ll be right back.

And we’re back! I’m talking to Lonnie Bunch, the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian Institutions. Um, is it Institutions or Institute? Sorry.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Institution.

Dr. Christina Greer: Institution. So the 14th secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Um, I’m so excited. Okay. We’re two out of three. I think we’re doing very well. Are we ready for question number four?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Okay.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. The National Negro Liberty Party nominated this man for president in 1904, making him the first Black person to run for the presidency of the United States.

Who was this man?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Hmm, 1904. Let’s see, Douglas is [00:23:00] dead. Uh, it’s not Du Bois. Um, geez, not Booker T. Washington. I don’t know.

Dr. Christina Greer: And, and I was working on a book about this, or a few papers about this. You know, Frederick Douglas was nominated for the Vice President.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Vice President.

Dr. Christina Greer: But this is the presidency and it was George Edwin Taylor.

So born to a free mother and enslaved father, Taylor lived much of his life in a foster home in Wisconsin before moving to Iowa as an adult, where he became a journalist. He owned and operated a Black newspaper and was also a justice of the peace and police officer. He was very active in local politics and was a member of both.

The Republican Party and the National Negro Democratic League, but eventually left to join the Liberty Party. No newspaper supported the third party and state laws kept the party from listing their candidate on official ballots, but Taylor’s presidential run was short lived and unsuccessful. He eventually left the third party in return to the Democratic Party.

So [00:24:00] I was working on a project about all of the people. the Black people who have run for the presidency, which culminates in obviously the election of Barack Obama. Um, but I was surprised at the number of Black women who ran for the presidency. And it’s largely a story about the role of, we call them third parties, but I say alternative parties, um, and leading to the larger inclusion of Black people in small d democratic politics.

So all of my students know my favorite president. is Lyndon Baines Johnson. Do you have a favorite president?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: It’s funny. Um, my favorite president is Lyndon Baines Johnson. Um, and, um, because I think if you look at what transpired under his leadership, not just the civil rights acts, but the kind of great society basically saying, building on what FDR did and can’t leave building on what the Freedmen’s Bureau did.

He said it is the government’s responsibility to make a country better, provide fairness for its people.

Lyndon B. Johnson: This Civil Rights Act [00:25:00] is a challenge to all of us to go to work in our communities, in our states, in our homes and in our hearts to eliminate. The last vestiges of injustice.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: He is sort of, you know, number one on my list, maybe behind a blanket, but pretty close.

Dr. Christina Greer: Well, and you know what I love about, uh, LBJ is that I respect the movement. So a lot of people You know, when you look at his career, he started off as a racist segregationist, you know, Texan from rural Texas, but over time, as the times changed and as his role in leadership change from member of the house to senator to vice president to president, he evolved with the changing times.

And I respect the movement, if you will, where he didn’t stay stagnant.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: And I think the other thing to keep in mind is he grew up with Mexican community, so therefore there was this sense from him that it wasn’t just all [00:26:00] about the white community. And I remember he was a teacher and many of his students were Mexican.

And so I think that you had that route, but then I think you had this evolution of saying. What makes sense for the country and I’m going to do that. And I think as a southerner, he was able to sort of get people around and say, look, I may not like all of this either, but you’re going to come along with me to change the society.

And so I’m a, I’m a big fan of, of LBJ and I think that the other person I’m a big fan of who should have been president was Charlotta Bass. Who was the editor of the California Eagle, um, who ran for vice president in a third party in the, in the 1940s. Um, I admire people who bring creativity, who bring a commitment to change, and Charlotta Bass was just one of the most brilliant people that not everybody knows about.

Dr. Christina Greer: Now, do you think Lonnie will ever have a Black female elected president? in our lifetime, not, [00:27:00] not someone who’s appointed, but someone who is elected, considering we don’t have, we’ve never had a Black female governor elected in the history of the United States as you very well know, and that’s an executive position.

And we’ve only had two elected Black female U. S. senators, which a senator is not an executive of a state. Um, do you ever think we’ll see that?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: I mean, I think we will, um, but I think that it is going to be a struggle and it’s not going to happen tomorrow. Um, you know, we haven’t had a woman president. Um, and so I think that what you’re seeing, though, is how do you create the generation of people who are ready to provide that leadership?

And I’m seeing more and more of that, um, at the state level. Um, and I think that, so I’m optimistic. No, let me put it this way. I’m hopeful, but not always optimistic, but the barriers of gender, the barriers of race, um, the fact that we had a Black [00:28:00] president means the barriers are not, not knocked down that we had somebody who was able to leap over those barriers, but those barriers are still there.

Dr. Christina Greer: Right. I always tell my students I’m pragmatically optimistic.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: You know, that’s why I do hope, you know, there’s always hope. I’m not always optimistic, but I’m always hopeful. Hope is so crucial to understanding Black life. Um, it is hope and it’s an, and it’s aspirations and it’s ability to articulate in quiet ways. The hope of the country. Um, and that’s what’s so powerful to me about African Americans, that they, you know, we used to say that John Lewis was the conscious of Congress.

African Americans are the conscious of America.

Dr. Christina Greer: Absolutely. Oh my goodness, Lonnie Bunch, I could talk to you for hours. Okay, we got to move on. We’re going to question number five. Are you ready?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Sure. I’m like, I’m in a slump, so hopefully I can answer this one.

Dr. Christina Greer: But as we say on the [00:29:00] Blackest Questions, Black history is American history, and we’re all here to learn together, right?

My educator hat is always on.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Yeah, but as a scholar, I’m like, man, I hate to not be right.

Dr. Christina Greer: Well, here’s the thing, Lonnie, to be fair, every time I’ve gone on my Grio siblings’ podcast, so that’s Toure, that’s Panama Jackson, that’s Michael Harriot, for our listeners out there who listen to their podcast, I’m 0 for whatever the number is.

There’s something about my brain, I think when I’m in the hot seat, it’s the Jeopardy nervousness and you know, it’s like, what is your middle name? And I’m like, I don’t know. You stumped me. Like next question. Um, okay. Question number five, the earliest recorded written protest toward ending slavery in America was penned by a small group of people in 1688.

What community did these people belong to?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Charleston, South Carolina.

Dr. Christina Greer: We got to go a little more north.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Really?

Dr. Christina Greer: To the German [00:30:00] Quakers, who lived in Germantown, Pennsylvania, who call themselves. The Society of Friends. Now I grew up on the, on the cusp of Germantown and Mount Airy. So this is, we’re in my backyard from my childhood. So the group of four friends wrote a letter denouncing the slave trade, calling it a grave injustice against their fellow man.

They wrote, and I quote, what thing in the world can be done worse toward us than if men should rob or steal us away and sell us for slaves to sleep to strange countries. The letter was submitted to a local Quaker governing body in Dublin, Pennsylvania that met monthly. They chose to pass the petition onto a higher governing body that met annually in Burlington, New Jersey.

The request to end slavery in Quaker communities was denied, but most Quakers living in Germantown refused to own enslaved people and became known to produce the finest linen goods in the region without using any slave labor. And in 1776, Quakers formally banned [00:31:00] slaveholding among their members. Now, I went to the William Penn Charter School that was started in 1689, founded by Quakers.

I grew up in Germantown and Mount Airy where this is the area of Quakers as abolitionists. And why do you think these, this history isn’t discussed as widely as one would think?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Part of it is that America has trouble looking at its own tortured racial past that America really struggles with somehow suggesting that these are stories that are not important, that could be divisive Rather, to me, stories like this of the Quakers is really the best of America.

It is people saying that America is not a static place, but a work in progress. And that, therefore, we’re going to continue to challenge, to push, to illuminate the problems to move the country forward. So I think that it really is a difference in philosophy between those that believe that the country is [00:32:00] aspirational and needs to be pushed to move to its highest ideals versus those who kind of like to believe, oh, we’re already at the promised land.

And those of us that grew up in the Black church know you’d never at the promised land. You just try to get there.

Dr. Christina Greer: That’s right. Now. I always tease you because as brilliant as you are, you’re always just so humble and say, Oh, Chrissy, I’m just, I’m just a kid from Jersey, which is far, far from the brilliance that you have given, you know, us, uh, in the world with the Blacksonian, uh, and your vision on so many different projects and so many different museums leading up to the culmination of you being the 14th secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

But tell us a little bit more about where you grew up and what kind of community fostered your love of knowledge.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Well, you know, I grew up in a town that was overwhelmingly Italian in New Jersey. So I grew up speaking Sicilian. I still curse in Sicilian. Um, and, but I wanted to know [00:33:00] that some people treated me wonderfully and some people treated us horribly.

We were the only Black family in the neighborhood. Um, and I thought that if I could understand history. First history of this town and then history of America. I could understand not just myself, but understand how America struggles around issues of race. But I was fortunate because, um, I had parents who were teachers and so therefore the value of education, the importance of reading.

And, um, so for me, history became both a way for me to understand myself, but it also became my tool to change America. To say that the stories need to be remembered. Um, I can tell you exactly, exactly when I fell in love with history. My grandfather died the day before I turned five. So he was reading to me, and he came across a picture of school children.

And I don’t know if they were Black or white. And, um, he said, Oh, you know, this picture was so long ago, these kids [00:34:00] are probably all dead. And when you’re four, you’re like, people that look like me are dead? How can that be? And then he said something I’ve never forgotten. He said, isn’t it a shame that people could live their lives and die and all it says under the picture is unidentified?

And I was stunned. How could people live their lives and be unidentified? So, really, my whole career has been very simple. I’ve tried to make the invisible visible. And give voice to the anonymous and it really came from that moment of my grandfather saying that’s wrong. And so I really have felt that part of the job of a historian is to make sure that we help a country remember.

Dr. Christina Greer: Ugh, you are a national treasure Lonnie Bunch. I can’t even, I can’t even take it. I mean, I think the importance of educators…formal and informal are so crucial to who we are as, as a people, but I really think that what you’ve brought together in your career, various museums is to also inspire us to want to be educators in our humble [00:35:00] lives, whether we are rock stars or professors or folks that just, you know, like my grandmother who was a nurse’s aid, not a nurse, right? But worked for the nurses and the dignity and the pride that so many people have and the knowledge that they have that they can pass on to other people. I just…

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: And also the strength. You know, I think of my grandfather who started out life as a sharecropper and decided he was going to find a way to go to college, find a way to go to dental school, become a dentist.

How does somebody do that? What is the strength of our families? You know, in some ways, what African American history tells us is, one, the struggles. But it tells us how an individual or a family can change the whole trajectory of the family going forward. And so that’s why I always think I’m hopeful, because I look at, I look at Black people believed in America that didn’t believe in them. Black people demanded an America that was horrific at times, um, that was not without loss and not without violence, but [00:36:00] yet these are people that persevered and move forward. I used to tell people all the time. I wanted to make sure the museum explored slavery and freedom because I didn’t want anybody Black to be embarrassed by their slave ancestors.

I wish I was as strong as my enslaved ancestors. And I wanted everybody to be able to dip into that reservoir of resiliency of strength, of hope, of desire to see a day that they couldn’t see for themselves, but they knew it would be there for their grandchildren, their great grandchildren. I want that hope to be what springs eternal in the Black community and springs eternal in America.

Dr. Christina Greer: Oh, I’m talking to Lonnie Bunch, as you all can hear. I’m just… I am in awe by the way your brain thinks about Black people as individuals and a collective. And I’m so thankful that you were a historian and decided to go into the field of museums to bring this [00:37:00] knowledge and this passion and this hope to all of us.

I’m going to take a quick commercial break. I’m here with Mr. Lonnie Bunch, the 14th Secretary the Smithsonian Institution. You’re listening to the Blackest Questions. We’ll be right back.

Okay. We are back. I’m with Lonnie Bunch, the 14th secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Lonnie, now it’s time for Black Lightning. This is my favorite round. This is the bonus round where there are no right or wrong answers. I just want you to tell me the first thing that comes to your head and your heart, and that’s where we’ll go.

If you could meet any historical figure, dead or alive, Who would it be and why

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: James Baldwin, James Baldwin was one of the greatest authors of the 20th century and his vision of what fairness was, his vision of the importance of history. I mean, James Baldwin is the first person I read that said. History is really about today, not just in the past, and that we’re carried by it in many ways.

So to be able to [00:38:00] sort of talk to James Baldwin, someone who really wrestled with issues of sexuality, identity, um, he would be the person that I’d love to have my first conversation with. And then my second conversation would be with the oldest relative that’s named Bunch. Who was enslaved and to be able to understand her life and her hopes and her fears.

Dr. Christina Greer: Oh, I love that. Okay. So if you could live anywhere in the world, where would you live?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: I kind of like Washington, D. C. I really like Washington, D. C. I like the, the, the turmoil that is the political part of Washington, D. C. Um, and so, yeah, I think that this is home. And if I could live anywhere. This would be it.

Maybe if I had a second choice, I’d end up, um, living in London. I love the diversity of London.

Dr. Christina Greer: I absolutely love London, too. Um, what’s your favorite time period?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Oh, definitely 19th century. The 19th century. [00:39:00] It’s so important to look at the, at the challenge of enslavement, to look at the struggle for abolitionism, to look at the transition from being enslaved to being free during Reconstruction, um, to look at the hopes of change and then the counter revolution of racists fighting against Reconstruction and fairness.

I think the 19th century is the place where you understand what it means to be an American and also can draw hope. But it reminds you that this struggle is a struggle that will happen every day as long as there’s an America.

Dr. Christina Greer: Mmm. Okay, what’s the last book you read?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Ha ha ha ha ha. Okay, um. The last book I read was a book on the history of slavery in Guyana.

I’m very interested in how nations around the world have been shaped by [00:40:00] slavery. Um, and so there’s some really interesting work that’s being done about slavery and the fight for freedom in Guyana. That’s probably the last book I’ve read, but the one I’m reading now is fascinating. It’s a book that looks at the impact of the crack epidemic on the United States.

Dr. Christina Greer: Donovan Ramsey’s book?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: That’s right.

Fascinating. So that’s what I’m doing now.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay, now here’s a hard one. What’s the best book you’ve ever read?

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Wow, um.

Dr. Christina Greer: And you can choose one of many.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Okay, I think obviously the most important book as a historian I’ve ever read was John Hope Franklin’s, From Slavery to Freedom.

Which, you know, sort of was the Bible and is the Bible. Um, I think that the book that I always keep coming back to is anything that includes poems by Langston Hughes.

Dr. Christina Greer: Mm-Hmm. .

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Um, I think Langston Hughes captures an urban [00:41:00] sense and an urban feeling for me that is just amazing. He captures the rhythm of jazz.

Um, and so I think that, um, whenever I’m in trouble, I pull out Langton Hughes.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. Favorite genre of music.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Oh, rhythm and blues and soul, you know, I can, I can sing badly every Motown song ever done. Um, and I think my daughters, even though they were raised in the world of hip hop, they like, okay, dad, we know who The Shirelles are, thanks to you.

So, um, that’s my favorite genre.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay. City with the best food.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: New Orleans.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Not even close.

New Orleans.

Dr. Christina Greer: Not even close. Okay. All right. Last question. The most impressive Black figure of the 20th century.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: You know, who’s the most impressive Black figure to me in the 20th century? Um, is [00:42:00] yeah, let me say it that way.

I really am. I’m struck by the power of Mary McLeod Bethune. I’m struck by her both her vision as an educator, which laid a kind of foundation of education, but also her involvement with the New Deal and with FDR, recognizing that it’s essential for African Americans to have a political voice as well.

So, I think that she’s extremely powerful and extremely important. Um, I also think that A. Philip Randolph, um, is somebody who really deserves to be remembered, not just for the March on Washington in 1963, but the proposed march in 1941, and the struggle for sort of demanding Blacks be treated fairly from World War I on.

So, um, it’s hard to choose, but there are some amazing people.

Dr. Christina Greer: Lonnie Bunch, I want to thank you so much for playing along with us. I want to thank you for taking the time to join The Blackest [00:43:00] Questions and sharing your brilliance and your vision and your hope with all of us. You did very well, by the way.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: Nah, I’m, you know, I’m an A student. I like to be perfect, but okay.

Dr. Christina Greer: Okay, well, that just means you’ll have to come back and play again.

Secretary Lonnie Bunch: And it means that what I want everybody to realize is you can never know it all. You have to keep learning.

Dr. Christina Greer: Absolutely. I want to thank you all for listening to The Blackest Questions.

This show is produced by Sasha Armstrong and Jeffrey Trudeau, and Regina Griffin is our Director of Podcasts. If you like what you heard, subscribe to this podcast so you never miss an episode, and you can find more from theGrio Black Podcast Network, on theGrio app, the website, and YouTube. Thanks for listening.

Writing Black: We started this podcast to talk about not just what Black writers write about, but how Well, personally, it’s on my bucket list to have one of my books banned. . I know that’s probably bad, but Ooh. I think spicy. And they were yelling N word, go home. And I was looking around for the N word because I knew it [00:44:00] couldn’t be me ’cause I was a queen

But I’m telling people to quit this mentality of identifying ourselves by our work to start to live our lives and to redefine the whole concept of how we work and where we work and why we work in the first place.

My biggest strength throughout, throughout my career has been having incredible mentors and specifically Black women. I’ve been writing poetry since I was like eight. You know, I’ve been reading Langston Hughes and James Baldwin and Maya Angelou and so forth and so on since I was like a little kid. Like the banjo was Blackly Black, right?

For many, many, many years. Cause sometimes I’m just doing some that want to do it. I’m honored to be here. Thank you for doing the work that you’re doing. Keep shining bright and we, and like you said, we’re going to keep writing Black. As always, you can find us on theGrio app or wherever you find your podcasts.[00:45:00]