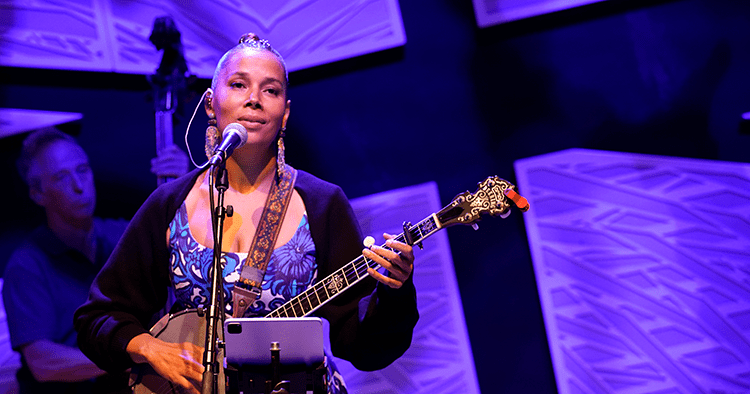

Grammy Award-Winning artist Rhiannon Giddens has always been vocal about Black people’s pivotal role in the origins of country music. The conversation surrounding those contributions has reignited as Beyoncé’s new music debuted at the top of the country charts. Giddens plays banjo on Beyoncé’s track “Texas Hold ‘Em,” and during her conversation with Writing Black host Maiysha Kai, Giddens shares that the instrument’s history is “Blackity Black.” The pair also discuss Gidden’s projects, including an opera about an enslaved man and her first children’s book. This conversation was originally recorded in October of 2022.

READ FULL TRANSCIPT:

[00:00:00] You are now listening to theGrio’s Black Podcast Network, Black Culture Amplified.

Maiysha Kai [00:00:07] Hello and welcome to this week’s episode of Writing Black. Now, if you’re a regular listener, you might already know that in addition to being an avid reader and a regular writer, I am also a musician. A Grammy nominated musician. So, you know, I’ve been in this music game for a minute. And so when I have musicians on the podcast, particularly singer/songwriters, I am really, really excited. And the guest we have on today is somebody I’m really excited about, Rhiannon Giddens, who is a Grammy nominated, MacArthur genius, writer and musician. Who has written in multiple genres and I’m just so excited to have her here with us today. Some of you might know her, if you are like me, a fan of the show, Nashville. Rhiannon was on Nashville. She’s also, you know, produced albums. She, you know, there’s so many things to talk about and we’re going to talk about them all in the podcast. But hi, Rhiannon. Thank you so much for joining us.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:01:13] Hi. Thanks for having me.

Maiysha Kai [00:01:16] And joining us all the way from Ireland. So, you know, we’re working with a major time difference here.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:01:21] Well, there’s a smaller time difference than you think. I do still live there, but I’m actually in L.A. right now.

Maiysha Kai [00:01:28] Okay. Well, good. Okay. So we’re only 2 hours apart right now. I’m in Chicago. You’re in L.A. I love it. And you know, we are here to talk about your newest piece of work. We’re going to talk about all of your work. But your newest piece of work is Build a Home, which is this really, really lovely children’s book that you’ve just produced, which I will admit I did not expect from you at this juncture. Tell me, how did this project come about?

Rhiannon Giddens [00:01:59] Well, it was I believe the last time you and I talked, it was still pandemic. It was still pandemic times or you know. And those kind of connections are really, really important. Like, I just remember kind of going, oh, I have a little bit of my let’s keep talking. Cause, you know, I’m not getting this here in Ireland. I mean, I love Ireland, but like, you know, it’s a different culture and it’s a different place. And when the lockdown was was happening with the pandemic, we were locked down pretty hard. You know, it just kind of opened up new vistas than I, I had before. And, you know, doing children’s books has always been sort of a a dream of mine. But it was really not until the pandemic lockdown that I could see an avenue for that and build a house kind of became the song kind of became a way in to that world, which I couldn’t have really planned or expected.

“Build A House” [00:03:05] You brought me here to build your house, build your house, build your house. You brought me here build your house and grow your garden fine.

Maiysha Kai [00:03:18] For you being a songwriter, there is obviously a really organic symbiosis here in terms of what that means. And you’re also a parent. So, you know, writing a children’s book, I would assume, takes on different dimension there as well, I guess. Tell us about the song because I mean, you write like Home took on a totally different meaning to all of us, you know, during the the early days, especially of the pandemic. I refuse to say it’s over. It’s not, you know, because we’ve adapted. Let’s say that we’ve adapted. But in those early days when we really didn’t know what to expect, where to go, what to do, how to live at home, took on a new meaning. So, yeah, like let’s talk about this writing process of like going from song to.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:04:12] To text what i s, is, yeah, it was really interesting, I guess, because I was just really frustrated with being locked down during like the height of the protests in America. And I’d been already thinking about like, what is it? What is home mean? What does it mean? Where am I? Like, what’s going on right now? I couldn’t get home. Home being in that instance, North Carolina or the United States. And so all of those things become you know, I, I suddenly had a small, tiny window into the immigrant experience, you know, particularly years past, where like when you left, like that was it, you know, you weren’t going back. You were lucky. A few other folks from there, all of these kind of things, you know. And so it kind of gave me a sound tiny, tiny, tiny window into that. But also I was just really frustrated with the continuing ignorance. About where American history comes from and just how we keep having to tell the story. And I don’t know. So I wrote the song Build a House because, you know, I was just sort of like, oh, that is just like freakin brought us over here to build this whole freaking thing and now you don’t want us to have a fair share of it. That doesn’t make any sense.

Maiysha Kai [00:05:27] Right.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:05:27] Just, you know, just because I’ve thought about this stuff for a very long time. And so, like, you brought me here to build a house, I just kind of came and then I wrote the rest of the song. And the thing is, like, when you think about, because what happened was, you know, Yo-Yo Ma reached out to me about recording something together for Juneteenth, and I had just written Build a House. So we did that. And somebody said in the comments, this could be a kid’s book. And I was like, Ha, you know, I’ve always wanted to do kids books. And so the thing about the way that I write songs a lot of the time is that I write very heavily influenced by folk traditions. And so those traditions are very, there are things that happen within writing a ballad that work kind of hand in hand with what you do for anything, a kid’s book, you know, the the language should be very direct. The it’s repetitive sometimes and it’s just it’s a very kind of the language is you’re packing a lot into a very little and that’s what you do when you write a ballad and it really is kind of what you’re doing when you write a children’s book. So, you know, Candlewick, Karen Lotts at Candlewick Press, you know, saw the, I think, potential in adapting these lyrics for a kids book. And so, you know, they wanted to jump in with me and to this children’s book publishing world, which is amazing.

Maiysha Kai [00:06:49] So no, it is amazing. And I love the story and I love I mean, the illustrations are also amazing. So let’s shout out Monica Mikai, who illustrated this book.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:06:59] She’s everything in this book.

Maiysha Kai [00:07:01] It’s really gorgeous. So I’m sure the idea of coming, you know, it’s like I mean, these opening lines you brought me here, as you just said, “you brought me here to build your house, to build your house, to build your house.” And I think, like, you know, I mean, you look at this illustration and I think for, you know, African-Americans, you know, who are descendants of the transatlantic slave trade, that’s always what we have to come back to is like, you know, you brought me here then, you know, and now you don’t want me. But, you know, and that’s like that’s its own thing, right? You never did. You never did. But I was useful to you.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:07:41] You wanted my labor.

Maiysha Kai [00:07:42] You wanted my labor. You want my labor. And I love that you just talked about the folk tradition because, you know, one of the things I love about you as an artist, you know, and for people who are familiar with Carolina Chocolate Drops, you know, that’s you. Your work as a historian, as a music historian, as well as an artist, like somebody who really brings us back to the very, very African or African-American roots of folk music, of country music, of blues. You know, I feel like you gave me an entire history of the banjo once, which, you know, I know is your primary instrument. You know, why do you think I mean, you know, as you said, we keep having to tell this story over and over again of how foundational we are, not just to the structural foundation of America, but also the cultural foundation of America. Is that like something that you consider part of your life’s work, or is it just something that is. Adjacent?

Rhiannon Giddens [00:09:03] I mean, it’s kind of it’s kind of my life’s work. I can’t I can’t get away from it. And and what I feel like I’m I can’t leave is there is that idea of the cultural history of the United States. And, you know, just as so many buildings were built by enslaved people, not only the buildings, but the brick. You know, when you think of the brick itself was made by enslaved people some so many times. But people when they see the edifice, they see the building, they they don’t see that. And I feel like that’s the case with American music. You see American music and there’s some places where you can where it’s been allowed to see what our contributions are. And then there’s a lot of places where it has not been allowed to see our fingerprints in the brick, you know? And I feel like that’s what I’m doing musically. It’s like musical archeology, I guess, because I feel like it’s because music has been used as a tool to divide us, and it’s always been a tool to bring us that together. And that’s why they use it, because they see how powerful it is. And it is one of those places culturally where people come together as through music, through art, and so it is there for use by the folks in power. That very same tool is used to kind of, you know, because they see the power of it. I mean, it is one of the deepest connections to being human that we have. And that’s immense, you know, and our contributions and our creations and our innovations within the fabric of American culture, you know, like the more that we can make that clear, that it’s been a part of it from the very beginning before Jamestown, you know what I mean? It’s been a part of it from the very beginning. We kind of go back to the Caribbean. You know, the clearer that is and the more people understand that, the more people understand how artificial the divisions are I think.

Maiysha Kai [00:11:04] I agree. And I know I want to talk about that more. We’re going to be right back, though. We’re going to take a minute for a commercial break and we’ll be right back with more Writing Black. Okay. And we are back with Rhiannon Giddens, the Grammy Award winning, MacArthur Fellow who has written this amazing children’s book, Build a House, and who has also, you know, we were just talking about music history and how integral we are, African music, African-American music to the American cultural tradition, which is work that you’ve been doing for a really long time. You know, you brought to fruition an opera. And, you know, listen, I know nothing about, I know about writing songs. I do not know about writing an opera. Like, I don’t know anything about that process, how that works. And I would love for you to tell us about the inspiration behind a behind it, the in just the process itself. I think that’s a whole other genre that we don’t get to hear a lot about on this show. But again, when we talk about the writing process, this is as relevant as any other. So I’d love to hear about that, how that came, you know, into fruition.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:12:27] Yeah, I mean, it was pretty intense. I mean, you think about like a three minute song. Well, you’ve got to go to an hour and a half for a two hour opera. Like, it’s it’s just it’s. And some things were the same. Some things were different. You know, I was lucky or smart or whatever, enough to know who to collaborate with. So I collaborated with Michael Abels, who is the, he’s a film score. I mean, he’s a composer and he writes a lot of film scores. He does a lot of stuff with Jordan Peele. And that’s how I kind of got to know him, was the music of Get Out, which I thought was really amazing and so I reached out to him. Yeah. So I reached out to him to, you know, kind of collaborate with me on this project. I said, Look, I can write the libretto and I can write the music like in terms of the songs and the melodies and stuff. But I don’t know how to orchestrate. I don’t know the orchestra. It’s a really big scale project. And you know, he came on board and it’s just it was an amazing process. But I had to start with the man himself, which is Omar bin Saeed, who was a Senegalese Koranic scholar, you know, sold into slavery. And he was he lived as a slave, an enslaved person for over 50 years in North Carolina. And he wrote his autobiography in Arabic. And it’s the only document we have, you know, of an enslaved person writing in Arabic, writing their own their own story. And it’s kind of incredible. And I was from North Carolina. I am from North Carolina. And I didn’t know about this at all. When I found out about it, I was just stunned and shocked and angry as usual.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:14:01] So I took it, took it on, even though I didn’t really know what I was doing. But that’s kind of where I think I work best is when I don’t know what I’m doing. So as long as I get the right people to work with and then I just kind of let the instincts and the ancestors kind of go. And that’s what happened with the libretto. I just the libretto being the words of the opera. So I just kind of let it flow. And, and. Yeah. I was really interested in trying to figure out what’s the story. You know, he was 37. He was captured at 37. You know, when you think about he survived the Middle Passage, he survived his first Masters evidently was a terrible, horrible, violent man that he ran away from all the way from Charleston, South Carolina, up to North Carolina like and Atlanta. He didn’t know anything about 37. It’s just a it’s an astonishing story. And it deserves a big a big stage. And it is opera also, we deserve opera and opera deserves us. You know what I mean? Like Black people have been singing opera like since jump and it’s it is a it’s an art form that came from folk music. You know, when you trace it all the way back to Italy and it was not ever meant to be only for some people, like that’s just become a thing. It’s become elitistized, if that’s a word. Which angers me because it is such a it’s a beautiful it’s a beautiful art form. And I think everybody should have access to it and. Then also our stories need to be told in that art form as well. So yeah, I have a lot of thoughts.

Maiysha Kai [00:15:38] I love those thoughts. Listen, the musician in me loves those thoughts and I want to talk about them more. We’re going to take a quick break and we’ll be back with more Writing Black. And we’re back with Rhiannon Giddens, who is an incredible singer, songwriter, children’s book author, now, librettist. We were just talking about opera and again, you know, our roots in that tradition. Is there a great artistic tradition that you can’t find Blackness in? I guess I haven’t found one yet.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:16:13] Nope we everywhere.

Maiysha Kai [00:16:17] Listen, if anti-Blackness is everywhere, that means Blackness is everywhere. Right.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:16:21] I mean, European literature. We there, too.

Maiysha Kai [00:16:23] Yeah. Yeah. Listen, we are all over.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:16:27] Dumas. I mean, you know, so.

Maiysha Kai [00:16:28] Exactly. Yes, exactly. That. His dad. All of that. Yeah. You know, this particular narrative also strikes me because, you know, we hear a lot about and I would say in tandem with your book, your your new book, like, we hear a lot from people like, oh, I don’t want to hear any more slavery narratives. I don’t want to, you know, like, like there’s some exhaustion, some like, you know, historical fatigue. And I would say, you know, for me, I’m not in that particular camp. I understand the emotional fatigue of it. I also, you know, we look at where we are right now in terms of this whole CRT listening situation here. I’m I make no bones about saying that’s inane. And, you know, and we look at a book like yours, we look at the kind of books that they’re trying to ban and who they’re trying to ban. Why do you feel it’s important to keep telling these stories?

Rhiannon Giddens [00:17:29] I mean, I really don’t feel like we’ve I feel like we’ve just started. That’s the thing that gets me. And I feel like I always get, why are we always gonna talk about race? I’m like, number one, y’all brought it up.

Maiysha Kai [00:17:39] Word.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:17:40] We didn’t start talking about race. We had no interest.

Maiysha Kai [00:17:44] Nobody was talking about before you.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:17:46] Okay. Let’s get that out of way. Number 2, we haven’t begun. We haven’t begun. Like we talked about actual conversation where everybody’s bringing an interest to get to a better place to the table. That’s not happening. Right. Three. I was just listening to a podcast about Billy the Kid because that’s what I do. I listen to historical myth busting podcasts. And you know how many movies have been about Billy the Kid? Like 40. He gets 40 movies and Harriet gets one. And we we talk so much about race. Like, how many World War Two movies are there? How many? You know what I mean? It’s just like where people say that because.

Maiysha Kai [00:18:27] She gets one, Stagecoach Mary gets a mention in “The Harder They Fall” like.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:18:32] Right, you know? And like, she actually has, like, an amazing life. Like, I mean, no shade on Billy the Kid, but, you know, he’s been done, right. I just think I think that people are just they don’t want to talk about it. So they say, why do we keep talking about it? Because I’m like, you actually just don’t want to talk about it because what it what it does is when you have substantive, really good conversations about race, what it does is that it shows how shaky the foundation is. It shows it’s just a house of cards. And it also shows where the true power lies. And people don’t want to hear that. They don’t want to hear that race has been used as a tool not only to keep some people as a permanent underclass, but also to keep everybody else is variations on of a theme. You know, you can’t talk about Blackness without talking about whiteness and the moving bull’s eye of it and the way religion is tied up in it. And and, you know, the way that people keep all the folks that are like under the 2%, like fighting each other. So they don’t realize that all the power is held by the 2%. So it’s just like, I get it, I get it. But like, some of us don’t have an option of not talking about it. I don’t actually think anybody has the option. I think our country is poisoned. And the poison will not run clear until we actually really talk about it, like in ways that mean that we need to be educated about it as a big hill, that’s a really big hill. I get it.

Maiysha Kai [00:19:59] It’s a huge hill. And we’re going to talk about the hill. We will be right back with more Writing Black. And we’re back. Rihannon, we were talking about the big hell of discussing race, discussing the legacy of slavery, discussing accountability. You live a very international life. How does that how is that like, I guess, further informing your craft? You know, living abroad, I know that there’s a lot of, first of all, there’s always been a lot of history in your music. But how is it informing, I guess maybe your writing and your politics now?

Rhiannon Giddens [00:20:40] I mean, just being being of removed has been really interesting. So being it’s a break in some ways, but it’s also frustrating and others because it means I can’t you know, I have to really plan my trips because I can’t be flying all over the place. And my kids live in Ireland and I have to, you know. Yeah. But on the other hand, it’s also a nice kind of pause and break because Ireland has. A very tough history, but it’s not mine. You know, so there’s a different kind of connection to it. I can see it as a as an ally, but not.

Maiysha Kai [00:21:16] Yeah, definitely a colonial history for sure.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:21:18] Absolutely. And like I am being there.

Maiysha Kai [00:21:21] Yeah. Well, yeah. When Queen Elizabeth passes, it’s like, whoa, you know? Yeah, I feel like Black Twitter was like, Oh, wait, Ireland said, hold our beer. Oh, yeah.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:21:32] Yeah, yeah. Black Twitter and Irish Twitter. We’re like having a party. It was funny.

Maiysha Kai [00:21:36] It was like a whole situation. Yeah,.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:21:39] My sister kept sending me stuff. I was like, Oh my God, this is so great. It is an interesting. You know, what I feel like when I’m in Ireland is that I feel like there’s a there’s a big pillar of American society of of Black and Irish collaboration that hasn’t really been explored other than a few words about tap, you know, in a very reductive way. But, but what happens with with the Irish is that they climb out of Blackness into whiteness, you know. And so it obscures some of that, you know, which is what happens over and over again. The Southern Italians did it, too, you know, they came in and it was like, oh hey, you know? And then it was.

Maiysha Kai [00:22:14] Like they are basically recruited to assimilate. And then, yes, like, you know, that looks appealing. And they can. So they do.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:22:21] Exactly. Yeah. Yeah. So yeah, I I’m really interested in and where those collaborations were and are and how we can look at that and go, this is a great example of how we do it. This is how we’ve done it. And we can’t let them cover it up because, you know, that is literally our superpower is collaboration and change and move, you know what I mean? It’s like an adaptation. And so wherever we’ve done that with other people, I think that’s what I’m really interested in. And that’s where all the great music stuff comes out of is all of that, you know, the edge, you know, rubbing up against the folks and then kind of creating this, this new amazing thing. And then, of course, it gets commodified and packaged up and sold back to us. And I’m like, wait a minute. And we get removed from it and then it gets sold, you know, on. So I mean, there’s bad parts to. But I’m really trying to like get to the good parts. And so it’s, it’s nice to be in Ireland and having these conversations with some of the, you know, I’m working with the University of Limerick and starting to have these conversations, you know, from the descendants of the groups that work together, like now we’re talking to each other and that’s that’s really cool.

Maiysha Kai [00:23:36] It is cool. Yeah, it’s very cool. We’re going to talk about more of that and more about Rhiannon Giddens and her incredible career when we come back with more Writing Black. So Rhiannon, we’re back. We were just talking about conversations being had like inter, intercultural, interracial conversations. I loved what you were just talking about, about, um, you know, the assimilation factor, which, you know, we talk about it like it’s, I mean, listen, when I say that, when I talk about assimilating, it’s like, first of all, we’ve seen that all over. We see it in the Black community. We see it outside the Black community. And I that’s I think that’s less of an indictment of the communities that assimilate than is of how a white supremacy functions.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:24:18] 100%.

Maiysha Kai [00:24:19] Do what you have to, obviously. So I want to make that clear. I think we all do it. We have to kind of do to survive. And, you know, I do equally feel like one of the things that you are so effective at doing and that I admire so deeply about you as an artist and a creator, is this preservation of particular American cultural traditions in which a lot of us don’t see ourselves right? Whether that be this folk music tradition that on an intellectual level a lot of us may understand. But when we think about what is Black music, right? We don’t think folk music we don’t like. It just doesn’t occur to a lot of people that country doesn’t occur to us. We don’t even though we’re all up in through. I know you started a project a few years ago with some colleagues in the industry. I’m hoping I’m going to say. Right. Our Native Daughters.

Our Native Daughters – “I Knew I Could Fly” [00:25:22] I follow the stars. I can read.

Maiysha Kai [00:25:30] And I like, you know, I want to talk about, like, that part. Like preserving our place in this American lexicon of, you know, as you just said, these things that are packaged and then handed back to us like they don’t belong to us in the first place.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:25:51] Right.

Maiysha Kai [00:25:52] You know, like in their work and preserving that.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:25:55] Yeah. This is the thing. It’s it’s like, you know, there’s two parts to it. It’s like the discovery of the actual our actual engagement in that in the creation of these of these types of music. And then there is the how we are erased from it. And like, you have to kind of grapple with both of those things. And that’s kind of, you know, from the banjo on, that’s been sort of what has driven me. And it’s like when you think about how important are being there is it wouldn’t be American music wouldn’t be what it is at all. You know, square dance calling, the way that American old time tunes are like all of these things are actually like completely wrapped up in our involvement in it. The Black string band being so popular, being so widespread, being, you know, they’re way before minstrelsy, you know.

Maiysha Kai [00:26:49] So I remember I was having a conversation with my partner really recently and I was saying to him, I was like, you know, you realize they used to train musicians so they can entertain the white people, you know, like, like we had our own organic thing, but also they would train these, like, string quartets. Like, that was like a whole thing that you would do at your parties and like, have your enslaved people in the corner over there with their, like, violins and their whatever, which I found is really interesting.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:27:19] And what they’re doing is they’re, they are bringing in a European dance music and dance styles, and they are incorporating that all together with, you know, what they brought over from Africa. And so they’re playing for themselves. They’re playing for white parties. They are actually carrying the musical DNA back and forth between the different cultural groups is the Black string band, you know? And so there’s a real, I think we still don’t know like enough about how important they were. And there’s there’s a lot of research that I’m drawing from that’s been done, but it’s like they were the ones who were like shuffling back and forth. I mean, 100 years before the minstrel show, you know, Black and Black people were playing the fiddle and banjo together, you know, and it wasn’t in the South, it was in Rhode Island, you know what I mean? It was up it was up north where it was written down that somebody saw that happen. I mean, it was happening in the South, obviously, but, you know, this was happening everywhere. It wasn’t like, you know, anyway, it’s it’s a long story to get from how did we co-create old time music and the beginnings of country music and bluegrass and actually made the banjo and were the only ones to play it for hundreds of years? Like, how do we get from that to all of it? Obviously, all of this is white music that was written in the Appalachian Mountains by, you know, Scotch-Irish people or whatever, you know, the story is.

Maiysha Kai [00:28:41] Right.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:28:42] So that’s the story to me. That’s interesting is like why when it happens, why it happens, it’s all happening at this point in history. You know, when you think about like leading up into the twenties where things start to get codified and commercial recordings and you know, then we start having images in the media and things and that’s how things get sort of cemented. But like it’s starting, it’s a it’s a fear, you know, it’s white people are afraid that the race is going to get dissipated into these colors, you know, which is why they’re so against miscegenation and so against anybody interacting together. And you just see it over and over again, this fear. And so we have to shore up our cultural identity as white people in America. Right. Because like we we need we are strong and we need, you know, so that’s where you start seeing it over and over and over again. It’s like this this trying to, you know, our connection to England and to Ireland and like, you know, the old country and this is our cultural heritage and that’s the good you know, these are the foundations of this of the country. And like Black people have nothing to do with that. They were in the fields singing their blues crap, you know? I mean, it’s like literally.

Maiysha Kai [00:29:50] Their spirituals, their call and response. Yeah, yeah.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:29:52] Right. And that’s what they do. And we do this and there’s no in between. And over and over again, the fear comes when there’s mixing. The fear comes when they see white culture start to want what this is, and then they start to change it and it goes back and forth. So it’s very important to keep them in separate boxes and that means they have the erase one of the main strands, which would be African-American, you know, creation in that music. So what it does is that it just continues this narrative of, you know, America was was based on white culture, whatever that is. And the Black people kind of survived in it and created some fun stuff that they get. You know, we get to, you know, use and make money off of. But like the culture of America, it doesn’t have anything to do with Black people. And that’s a really, really strong narrative thread. And it’s infuriating because it’s just the most untrue thing that ever was spoke. You know, American culture is African-American culture. Like that’s we’re there to stay. There’s no getting us out. Sorry. You know?

Maiysha Kai [00:30:53] Yeah.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:30:54] You know.

Maiysha Kai [00:30:54] Right. And without us, there is no you. There is no you know, without us. Exactly. And, you know, as we know, whiteness cannot define itself except for in contrast to Blackness. There’s also that and we’re going to talk about that more. And I also want to talk about another kind of siloing I’ve seen as soon as we come back with more Writing Black. Okay, so, you know, Rhiannon, I want to talk to you about something a little more personal. You know, I know when I went through the whole Grammy machine, one of the things that’s really interesting, so I was I was nominated in the academy I don’t even think exists anymore, which was the Urban Alternative Category, which I used to joke was like where they put all the Black people who weren’t like R&B and, and jazz and, and gospel. Like, I was like, they just don’t know what to do with us. They were like, okay, like, where do we put, like the Lenny Kravitz’s and the Meshell Ndegeocello’s. And, you know, the year I was nominated, Janelle Monae also got her first nomination. It was like, you know, so like, you know, just like all of us who didn’t fit into these prototypical Black genres. And as somebody who also I mean, as foundational as you have just proven and and restated that that Black influence is on American music just in general. You know, it’s not easy for them, is it? Like they just like I feel like the Grammys, you know, when we like here we are, this is like the biggest award you can get in music and. And this is not to take away anything from and listen like I will be I proudly am a Grammy nominee for the rest of my life. And I’m sure you are proudly a Grammy winner for the rest of yours. But it is so interesting to me that they have such a hard time knowing where to put us, right?

Rhiannon Giddens [00:32:46] I mean, that’s deep history. That’s deep history, though. And it’s like I’m always conflicted about the Grammys because. Yeah. That’s a whole nother topic.

Maiysha Kai [00:32:58] And I’m not trying to throw the Grammys under the bus.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:32:59] No, I mean. I have it. I didn’t get it back. You know what I mean? Like.

Maiysha Kai [00:33:04] Exactly that, right?

Rhiannon Giddens [00:33:06] But the thing is, it’s like the Grammys itself is not really what I’m talking about. It’s what the Grammys is based on, which is this.

Maiysha Kai [00:33:12] Right.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:33:13] You know, separation of music. And that goes back to the twenties. And we have to think about like the music industry is a very young industry is super young. When you think about humans and music, we’re talking millennia. We’re talking 100 years of recorded industry. Like, it’s very young. And it began on division. You know, because it’s like we had to I mean, it was like the record industry began to sell record players. That’s it. And I mean, like, this was not let’s capture all the beauty of the music now. It was like, let’s capture the music that we can then package up and sell back to that ethnic group. And so there was all this quote unquote, ethnic music like on these labels. And then they got the idea to go get stuff in the South. And then the Division of Race Records and Hillbilly Records. That’s where it all begins. And so everything was really branching from that. Even the idea of folk music gets coded as white music also, around this time. Again, this is the time I was talking about earlier with this kind of creation, this mythical creation of a white cultural heritage that is like that is what is the word. I don’t I can’t remember what all looks the same and that we’re not in there at all, you know. You know, the idea of a white guy with a guitar being the emblem of folk music when what is folk music? Folk music is music is blues. It’s you know what I mean? It’s all it’s just music that people created themselves to reflect what was going on in their culture. And even that was part of the music industry in terms of how it was marketed, it became coded as white.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:34:44] And so when people say folk music, they mean a very specific idea of what it is. It’s a white guy with a guitar or banjo strumming along, singing kind of ballady type stuff that’s connected to the Anglo Celtic tradition. That’s not what folk music is in my book, you know, but it’s like we have to fight against that. And what it does is it keeps perpetuating these divisions. You know, when you look at the like first big folk festivals, it was like all the Black people, you know, that these white folk stars were inspired by, were there, do you know what I mean? And it’s just like if you dig a little bit, you see them there. But are they on the main stages? You know what I mean? It’s kind of like I didn’t listen to Bob Dylan. I listened to who Bob Dylan listen to. I don’t know a Bob Dylan songs. I know like a few, you know, and that was my choice because I was interested in the source material. But it’s like, you know, again, you get something that is here and then it’s packaged up and it turns here and memories are short. A generation, 20, 20 years. You know, it’s true. What’s what’s recorded is what is from.

Maiysha Kai [00:35:42] Scratch, Elvis. And what do you get, right? Like.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:35:45] I mean, it’s just like it’s just the story is over and over and over again. It just doesn’t take away from, like, Elvis’s artistry. His honest, you know, his honest sort of like coming out of all of the cultures that he was being around.

Maiysha Kai [00:35:57] Admiration, his interpretation. Sure.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:36:01] You know, and like and all of that. But it’s just like, once again, when you get to who’s making the who’s making the categories, who’s profiting off of the categories, whose, you know, who is benefiting from this continued narrative? You know, like the banjo was like the Black right for many, many, many years. Everybody knew. Everybody knew. I was like every like pictures. Yeah. Like you show a banjo that’s Black people. Like, it was an emblem of Black people and for the fact that has been completely 180 degree turn. So even many people in our own community, most people in our own community don’t know that that’s powerful narrative rewriting and erasure. And we just have to put the blame where it belongs. Just like, you know, usually outside of the working class, it’s usually these people, you know what I mean? I don’t know.

Maiysha Kai [00:36:52] That truly makes sense .

Rhiannon Giddens [00:36:53] Yeah, I’m not saying it’s a conspiracy. It’s just the way that the structure is is made. I mean.

Maiysha Kai [00:36:59] At a certain point, it’s bigger than a conspiracy. It’s just it’s habit, you know? It’s like erasure becomes habit like anything else. Exactly. Well, you know, you as a historian, as a writer, as I would like to say and I love you know, you are a cultural archeologist, you’re a music archeologist. Who do you, who do you listen to? Who do you read? Who inspires you culturally? Who do you look to, I guess as a writer, since we’re talking about writing, who do you look to.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:37:32] As a writer? I mean, you know, all the greats. James Baldwin is like.

Maiysha Kai [00:37:40] Yes.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:37:41] Sometimes I’m like, why should I say anything? Because he said it all. You know what I mean? He’s just like so many things that he said so brilliantly. You know, musically, of course, Nina Simone is such an inspiration on the pure history front. I have to say, I’ve really been enjoying a lot. I like I said, I listen to history podcasts. And there’s a Canadian high school history teacher that has a podcast called Our Fake History. And it’s really, really brilliant. He takes, like, the myths and then he just busts them down, like piece by piece. And he’s he’s got a great and I listen to his one about rock and roll and I was like, Here’s your test, Sebastian. He’s your test. And he passed with flying colors. I was like, he, he did it just right. Because the thing is about history is that anybody who’s saying they know everything that’s like I they’re off my list immediately because history is an evolving discipline that says as much about the writer as it does about what they’re writing about. And as soon as you understand that, you realize, you know, there’s there’s a lot to be learned. And anybody who is, you know, going, look, it’s not about who did it first. It’s about who popularized it. Right? That’s you know, but but it gets mythologized as this and this and this and that obscures the actual community based energy that goes into history. You know, it’s like Galileo didn’t invent the telescope, but there’s like all of these people at the same time who were coming up with the same thing. And it’s this idea that he’s the one that we remember because he does some amazing things with it. So it’s kind of like, you know, anything for me that complicates the narrative is probably the right is probably the right story, you know, because the narratives that have a plot to them, you know, that are trying to do something, they’re usually the ones that are so simplified that it doesn’t invite any kind of discussion.

Maiysha Kai [00:39:45] Um, yeah. I love this conversation so much. It makes me so happy. Rhiannon Giddens You are first of all, you’re one of a kind and I just so appreciate you. I appreciate what you’re putting out into the world. I always appreciate talking to you and I appreciate this because now we have a whole new generation to appeal to with Build a house. You know, we built this house that we know as America. I love this book. I love talking to you. Thank you so much for joining us on this week’s episode of Writing Black.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:40:17] Thank you for having me. And one more shout out to Monica Mikai, who made the most amazing gift for family. And that little girl and her banjo, like, literally give me life every day. So it would be nothing without her. She did an amazing job.

Maiysha Kai [00:40:34] I love it. You guys check out Build a House and I have a feeling this will not be the last time we’ll be talking to you. Rhiannon, but thank you so much for your time and your candor and your perspective as always. So appreciate it. Thank you.

Rhiannon Giddens [00:40:49] Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Maiysha Kai [00:40:50] We will be back in a minute with more Writing Black All right. Let’s get back into it. Welcome back to Writing Black. All right. This is the part of the episode where I talk about what I’m reading and what I recommend. We like to call it my favorites. You know, one of the things, you know, that I said over and over again during my discussion with Rhiannon is just, you know, this idea of history, this idea of our place in history and making sure that that is not just recognized but celebrated. So, you know, I think one of the things she does so artfully is bring that history to the forefront. And, you know, we’ve been hearing a lot about Sister Rosetta Tharpe lately. We were talking about Elvis a little bit in our conversation, Sister Rosetta Tharpe was a huge influence on him. She was also really one of the foundational, if not the foundational figure in what we know now as American Rock and Roll, which is largely, still largely looked at as as a white American art form, but really has its foundations in the Black blues tradition. So, you know, as we try to instill this knowledge in younger generations, I highly recommend Sister Rosetta Tharpe by JP Miller This is a children’s book. I again, I cannot impress enough like how just these little early hints, this early knowledge can be so just game changing for for young readers, for young creatives, for young musicians like I was once.

Maiysha Kai [00:42:33] Another book I might recommend that is coming out from, you know, really an American treasure is the Green Piano by Roberta Flack. I remember being a child and one of the early books I read my my step mom used to take me to the library and she’d make me pick out a biography. And I remember reading a biography of Roberta Flack, and she talked about her family getting this second hand green piano or maybe even painted green. And it was like a tragic piano. Like like I feel like some mice had died and it had a little smell to it. But this is how she learned to play and be a songwriter. And she’s also written a children’s book called The Green Piano, co-written a children’s book based on that experience. So I’m going to say these two books on these two incredible Black women who are such integral parts of our American musical, musical tradition are books that you should be sharing with your little ones. And those are my favorites for this week. And we will see you next week on another episode of Writing Black. Thanks so much for joining us for this week’s episode of Writing Black. As always, you can find us on theGrio app or wherever you find your podcasts.