COVID-19 robs us of people, not just numbers: Where’s the Humanity?

OPINION: While the statistics surrounding coronavirus is very real, we are suffering the loss of real people

The racial divide in the mortality rate for COVID-19 is profound.

World Health Organization Director Dr. Tedros Adhanom last month predicted that 3.4% of people globally who contract COVID-19 would die. But many people didn’t know at the time who to truly visualize as part of the more than 185,000 people who have already died from the nearly 2.6 million cases globally.

With numbers of deaths growing by the thousands daily, it is necessary to seriously consider what these lives meant to those who will miss them. In this country, the groups most vulnerable to COVID-19, the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions, usually play critical roles in Black families and maybe the most necessary cornerstone of that community.

Those who died were more than just elderly members of society, apparently willing to exchange their survival for the betterment of the economy, according to Texas Lt. Governor Dan Patrick in a controversial comment last month.

READ MORE: Texas Lt. governor says grandparents are willing to die to save economy

They were mothers, fathers, daughters and sons, churchgoers, breadwinners and generation-shaping grandmamas. They brought laughter and hope to those around them; in some cases were the very glue that held their families together. Their absences no doubt create desolation and holes in each family unit.

The backlash to these sentiments by Patrick was swift and expansive, starting trends on Twitter of #NotDying4WallStreet and #IStayHomeFor.

Protect essential employees, not Wall Street.#NotDying4WallStreet pic.twitter.com/FRgBjbZzQd

— Industrial Workers of the World (@iww) April 18, 2020

While understandable, conversations comparing lives lost to the flu and COVID-19 or the contraction rates of the virus to the overall survival rates, also undermine the magnitude and wreckage this pandemic can cause a family, especially those already marginalized.

The unintended consequence of these juxtapositions is the belittlement of the actual human capital being lost minute by minute and cannot overshadow the reality that these are not simply numbers, they represent real people and incredible lives.

Some profiles of those who’ve passed from COVID-19 already illustrate that all too well.

READ MORE: Black people who have died of COVID-19

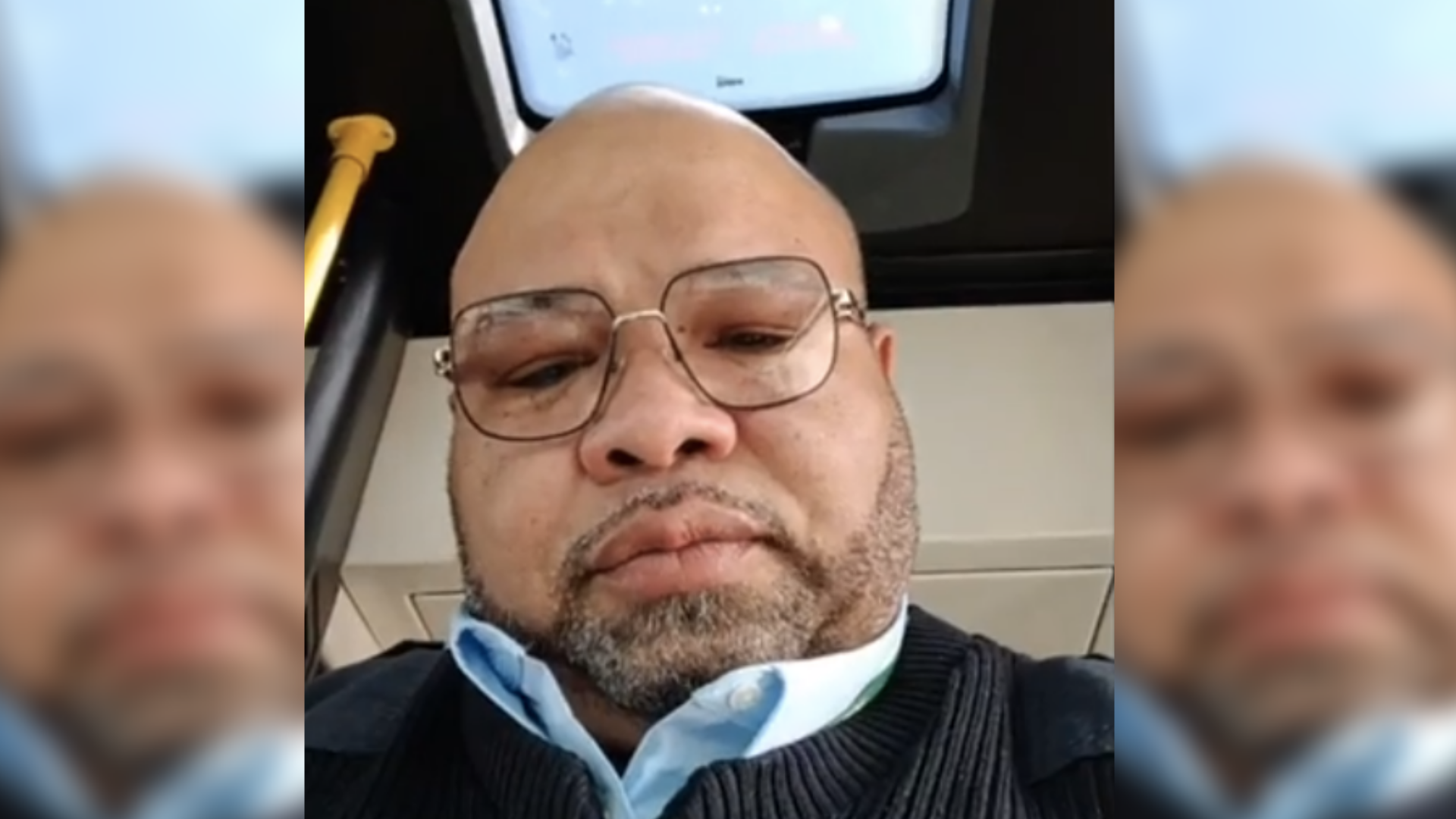

Jason Hargrove a courageous and energetic African-American bus driver, whose work was essential in Detroit, passed away at 50, leaving behind a grieving wife.

Alfred Golden, a grandmother to 35 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, passed away weeks shy of her 81st birthday in Savannah, Georgia. Golden was an African American educator described as “her family’s everything” and leaves generations behind longing for her wisdom, lessons and legacy.

As a community engagement professional responsible for creating sustainable programs and impactful philanthropy over the last eight years, I have seen Black families experience the most significant challenges across almost all determinants of wellbeing. That reality is only exacerbated when other factors like immigration status enter the equation.

The impact of disasters like a pandemic on marginalized communities is especially devastating because of the pre-existing lack of necessary resources like healthcare and money and the persistent inequities in accessing them.

READ MORE: COVID-19 hitting Black people hard? Too bad, get back to the plantation

According to a recent STAT report, “African Americans in Illinois, for example, accounted for 29% of confirmed cases and 41% of deaths, yet they make up only 15% of the state’s population. Michigan mirrors Illinois, with 34% of Covid-19 cases and 40% of deaths striking African Americans, even though only 14% of Michigan’s population is African American.

“The story is similar in Wisconsin, where ProPublica first reported that African Americans number nearly half of the 941 cases in Milwaukee County and 81% of its 27 deaths while the population is 26% African American.”

Compromised immune systems are the norm to a group of people more likely to have asthma, cancer and heart disease for causes related to poverty, environmental injustices and the toll of racism to name a few.

Layoffs and furloughs as a result of COVID-19 ring differently in this mostly underemployed demographic to no fault of their own, where unemployment is twice as high and even when jobs are had, they are usually underpaid.

READ MORE: 26 million have sought US unemployment benefits since virus hit

This means Black families rallying together for a collective strategy to overcome these racialized disparities need each other for their survival, especially the elderly and immunocompromised family members.

In Dallas, the most vulnerable neighborhoods in terms of health and economic disparity are in the southern sector which are also mostly populated by Black and Brown residents.

Researchers and city officials recognize the decades of neglectful practices that have led to disparate outcomes, even now when it comes to contraction and susceptibility to COVID-19. The county’s list of confirmed cases proves just that, with zip code 75227 leading with the greatest number of infected people.

Nonprofits serving in South Dallas are seeing a significant increase in demand for their services including food, diapers and clothing. Senior residents like Edgar Love, 68, living in one of the oldest African-American neighborhoods, understand these accessibility challenges.

It is time to re-imagine the role of the elderly and immunocompromised for what they truly are — critically essential.

Every community needs the culture-based stores and Black immigrants who run them, where people congregate and grab their flavorful spices, injera and coffee. They need the revered matriarch of the Black family, grandma, who does more than host Sunday family dinners to hold her family together.

Their absence leaves a lot more to mourn. Public and private discourse around the deaths due to COVID-19 must not be simplistic, one dimensional or apathetic.

It is time to reshape the conversation around any life lost to COVID-19 with respect to the tremendous value they have already added and would have added.

For me, that includes my dad, my whole world. He checks all the boxes — he’s over 60, survived cancer and a heart attack. As a result, he would most likely pay with his life if he contracted COVID-19.

While so many are working diligently to survive the physical and economic implications of this pandemic, each one of us must also take on the responsibility of helping guard and protect ourselves and neighbors psychologically by dignifying the conversation about our humanity.

We are suffering the loss of real people who matter beyond the numbers.

Bemnet Meshesha, MSW is a Community Engagement Manager, Social Justice Advocate and Researcher of Black experiences across the globe. She’s the President of the Dallas Fort Worth Urban League Young Professionals, and a Public Voices Fellow through The OpEd Project.

More About:News