Black people have been playing the ‘Squid Game’ forever

OPINION: Debt. Layoffs. Police brutality. Arrogant super rich folks. Even without the subtitles, we all get the message.

There’s been a lot of talk about what the Netflix mega-hit Squid Game means for Asian representation. How the Korean-language TV series is on track to possibly becoming Netflix’s biggest hit in any language, including English. How the show is part of the global ascendance of Korean culture, from the music group BTS to the Oscar-winning movie Parasite.

That’s all incredibly important stuff to talk about. But, as a Black person, when I watched the series with my teenage daughter, something else stood out.

Can we talk about the way Squid Game portrayed rich, ruling-class Americans? Because I was loving that.

Spoiler alert. If you haven’t watched Squid Game, go binge it and meet me back here. I’ll wait. Okay? We good? Let’s go on.

Squid Game is, at its heart, a cautionary tale about the way the rich oppress the poor. It’s a story of class struggle. A group of people in South Korea who are facing crushing financial debts are recruited to risk their lives in a violent series of games with the promise that the victor will win enough money to settle up with their creditors. It’s basically The Hunger Games rewritten by Bernie Sanders.

The players are a motley crew, including a North Korean refugee, a gangster, a gambling addict, and a disgraced business school prodigy. But it is soon revealed that a group of apparently non-Korean “V.I.P.s” is bankrolling the game. Every one of the players is portrayed more sympathetically than the V.I.P.s, who wear creepy golden animal masks and speak in accents that seem to be jarringly American.

The whole show is in Korean, so the American voices really, really stand out–like a Kobe Bryant jersey at a Boston Celtics home game.

The V.I.P.s are rude and entitled. The V.I.P.s use female servants as footstools. They make crude, juvenile sex jokes about the number 69. One of them tries to rape an undercover cop. Unlike the contestants in the Squid Game, who are humanized and sympathetic, the V.I.P.s are cartoon villains, hateful and irredeemable.

I loved every moment of it.

In America, we’re often encouraged to reach across the aisle, to try to find ways we can compromise with people who represent the rising tide of intolerance, ignorance and greed. When progressives call out the excesses of the super rich, they are often pilloried in the press as socialists, or un-American, or worse.

It’s good to see that, all the way in Seoul, Korea, filmmakers have the same view of the ruling class in America that many Black Americans have had for a long time. It’s an objective view, it’s a damning view, and it’s exactly what we thought all along. The animal masks the V.I.P.s wear in Squid Game aren’t really masks–they’re the true faces of members of the patriarchal power structure. They’re beasts preying on the have-nots. This isn’t some arguably subjective take coming from inside America, this is an objective view from thousands of miles away.

Like my man Frantz Fanon wrote in Black Skin, White Masks: “There are too many idiots in this world. And having said it, I have the burden of proving it.”

The idiots are on global display in Squid Game.

At one point in Squid Game, one of the characters tells a story about how bosses at a car factory he used to work at mismanaged the company and laid off workers. He and other workers took over the factory and fought with the cops. His memories of the factory takeover fade into the Squid Game. It’s all part of the same system.

Near the end of the series, a TV newscast playing in the background in a hair salon delivers the following report about the Korean economy: “The country’s household debt is rapidly on the rise, topping the global average.”

Debt. Layoffs. Police brutality. Arrogant super rich folks. Even without the subtitles, we all get the message. The Squid Game is a game Black people have been playing in America for a long time.

I can’t wait for season two.

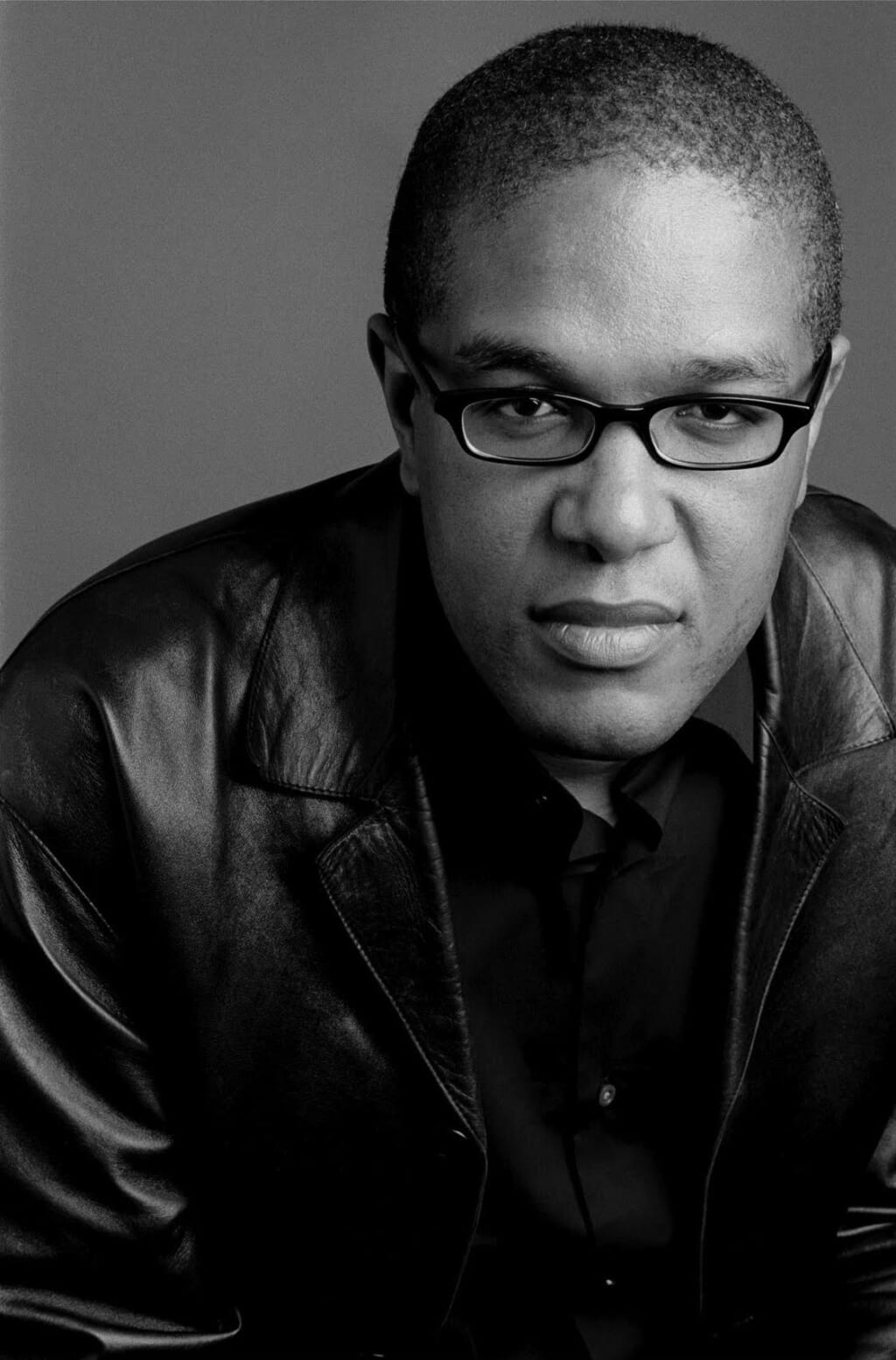

C.J. Farley is the author of five novels, including the new young adult novel “Zero O’Clock,” and a number of nonfiction books including “Before the Legend: The Rise of Bob Marley” and the national bestseller “Aaliyah: More than a Woman,” which was adapted into a hit movie for Lifetime television. Farley co-wrote and co-edited the book “The Blues” (Harper Collins), the companion volume to Martin Scorsese’s PBS documentary series. Farley’s short fiction has been featured in a number of anthologies including “The Vintage Book of War Fiction” and “Kingston Noir.” A graduate of Harvard, he has won a number of awards including an NAACP Image Award in 2020. Farley’s latest novel “Zero O’Clock” is about a teenager in New Rochelle grappling with the pandemic who finds herself in the Black Lives Matter movement. “The Hate U Give” author Angie Thomas said “Zero O’Clock” is “insightful, eye-opening, and inventive.”

Have you subscribed to the Grio podcasts, ‘Dear Culture’ or Acting Up? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!