10 years of Kanye West’s ‘Yeezus,’ a pushback against being ‘bound 2’ musical appeasement

Opinion: On the 10th anniversary of Kanye West's "Yeezus," theGrio examines how the artist made a polarizing album as a response against music conventions and the intentionality behind making "My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy."

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Kanye West’s “Yeezus” is a protest album.

On May 17, 2013, the Grammy-winner premiered his brand new song, “New Slaves,” by projecting an extreme close-up of himself on the side of buildings worldwide. The ominous, sparsely atmospheric track featured West rapping about how Black people experience racism regardless of class and how wealthy Blacks become indoctrinated with material possessions, becoming slaves to brand names that will line the pockets of their white owners and retailers.

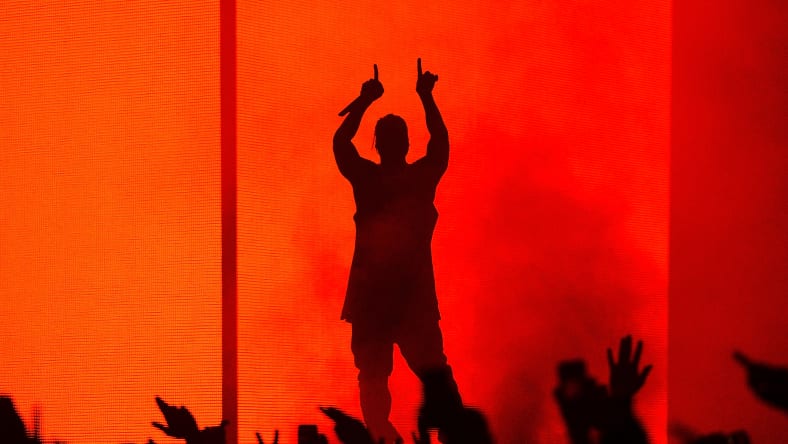

A week later, West premiered “Black Skinhead” on “Saturday Night Live.” Projected behind him were the words “not for sale” and Cerberus, the three-headed dog from Greek mythology, charged with keeping the dead from escaping Hades.

West’s lyrics and delivery were abrasive and enraged. The drums were rumbling, and the music was menacing. He was doubling down on the indignant Blackness that whites deemed uncouth and detrimental in society.

The world expected to hear a protest record on June 18, 2013, when West released “Yeezus,” his sixth solo studio album and follow-up to his critically acclaimed masterpiece, “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.” Upon listening, the world felt it was different from the album they were expecting to get, not from a lyrical or a musical perspective.

Rather than getting an album in the tradition of records like “What’s Going On” or “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back,” fans got a record that was sonically harsh and hard to follow, with lyrics that seemed unfocused, self-indulgent, and un-relatable.

“Yeezus” is West’s most polarizing piece of work. Some hate it. Some love it. But as time passed, it became clear that it was a protest record. It was West’s protest against sonic conventions and artistic placation.

“My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,” released in 2010, was one of West’s most critically acclaimed albums — if not most — of his career. It was the culmination of a comeback story from an infamous on-stage moment.

Following the public backlash from interrupting Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech during the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards, West went into self-imposed exile from America. Upon his return, he released an album that featured some of his most beloved songs, including “Power,” “Runaway” and “All of the Lights.”

For the next three years, West cemented the comeback by collaborating with Jay-Z on “Watch the Throne” and advancing his label GOOD Music. Out of that came the collaborative album “Cruel Summer,” which featured hits like “Cold” and “Mercy.” While any other rapper would consider this a superb victory lap or another hot streak, West saw it as something else.

West has been lukewarm to the album since the promotional run of “MBDTF” ended. He resented its success because of the sentiment that went into creating it. Up until that album, West was making music from his soul. Following a muse inside of him, West walked the line between paying homage to his heroes, like A Tribe Called Quest and Wu-Tang Clan, and trying to be progressive and forward-thinking.

For the first time, West made an album motivated to appease. Granted, he brought it on himself for the way he acted at the VMAs, but the reason why he gained his fans back bothered him.

“Dark Fantasy is almost like an apology record,” West would say in a 2015 “On Camera” interview. “It was me going back and spending six dedicated months and kind of piecing together what people liked about me to make an entire bouquet that they loved, that was the most listenable, that was the least challenging.”

For the follow-up to “MBDTF,” West was determined to challenge and even antagonize the listeners. Right from the first song, “On Sight,” that loud, distorted synth line bled into the skittering synth line featuring an angry, offensive West. It set the tone for an album that only had the glimpses of social commentary that were teased with its first two singles but was full of lyrics that were full of sexual aggression and uninhibited behavior, heard in songs like “I’m in It” and “Hold My Liquor.”

West reveled in the idea that many of the songs from “Yeezus” sounded nothing like his previous work. Three years before that, he had hits like “N*ggas in Paris,” “Cold,” “Mercy,” “Otis” and “Clique” that were meshed well with the hip-hop at the time, like the world of producers Mike-Will-Made-It and DJ Khaled. So, by the time “Yeezus” came, West loved the fact that the new album disconnected from the music of others.

“I’m not here to make easy listening, easy programmable music,” West told Zane Lowe on BBC1 in 2013. “I showed people that I understand how to make ‘perfect.’ ‘Dark Fantasy’ can be considered to be perfect. I know how to make ‘perfect,’ but that’s not what I’m here to do. I’m here to crack the pavement and make new grounds sonically and in society, culturally.”

When re-examing “Yeezus,” particularly songs like “Hold My Liquor,” “I’m in It,” “Guilt Trip” and “Blood on the Leaves,” West is revealing the plight of the hedonism that wealth and celebrity have afforded him. Indeed, the way the lyrics were crafted is nowhere nearly as discernible or focused as his previous album, and the playful humor of songs like “Gold Digger” and “New Workout Plan” were replaced with furious cynicism and regret.

For West, the feeling of the cadence and delivery was far more important than the lyrics. Rick Rubin, the album’s executive producer, said on the “Questlove Supreme” podcast that West came to him to help finish the album six weeks before release with finished music and zero lyrics written.

In hindsight, the tight 10-song set was the last that the world saw West release an album with a clear vision. From then on, albums like “The Life of Pablo,” “Ye” and “Donda” were muddy, self-indulgent, and foggy. His public antics, mental state, and offensive declarations have indicated from 2016 to today actually parallel those late-stage albums, presenting a man who seems out of touch with the world around him.

Public perception of West today would render a celebration or at least an examination of an album like “Yeezus” a practice of futility at best and an act of complicity for his harmful rhetoric at worst. However, West would not have fallen from such an elevated status without his music. Therefore, it’s essential to reflect on it to understand the complete artist.

“Yeezus” followed the footsteps of other influential Black artists who challenged fans following a groundbreaking, career-defining album. Miles Davis made “Sketches of Spain” after “Kind of Blue.” Prince made “Around the World in a Day” following “Purple Rain.” West felt confided by the success of “MBDTF” the same way Michael Jackson felt confined by “Thriller,” or Nas felt bound by “Illmatic.”

This version of West that made “Yeezus” shocked many people in 2013, but many people probably today wish this version of West were still around.

Matthew Allen is an entertainment writer of music and culture for theGrio. He is an award-winning music journalist, TV producer and director based in Brooklyn, NY. He’s interviewed the likes of Quincy Jones, Jill Scott, Smokey Robinson and more for publications such as Ebony, Jet, The Root, Village Voice, Wax Poetics, Revive Music, Okayplayer, and Soulhead. His video work can be seen on PBS/All Arts, Brooklyn Free Speech TV and BRIC TV.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!