Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Opponents of Black history try to whitewash our existence and minimize our contributions, but accurately reporting America’s past is impossible without us.

Haters must pick and choose which Black people to acknowledge and highlight, preferably those who achieved the so-called American dream without making white people uncomfortable. As the first person killed in the American Revolution, Crispus Attucks is a fine Black man to honor. So is Booker T. Washington, whose agrarian brand of racial progress always seemed less threatening than the scholarly version W.E.B. Du Bois espoused.

The world of sports is full of Black heroes that historians can’t ignore, though it helps when the athlete ignores societal conditions. Best if the athletes focus on the vacuum — the field or the court — not the racism afflicting their non-athletic kinfolk. Barred from mainstream pro sports leagues well into the 20th century, we started dotting the landscape before the civil rights era peaked. Jackie Robinson broke the color line in Major League Baseball in 1947.

Orenthal James Simpson was born three months later.

Sports

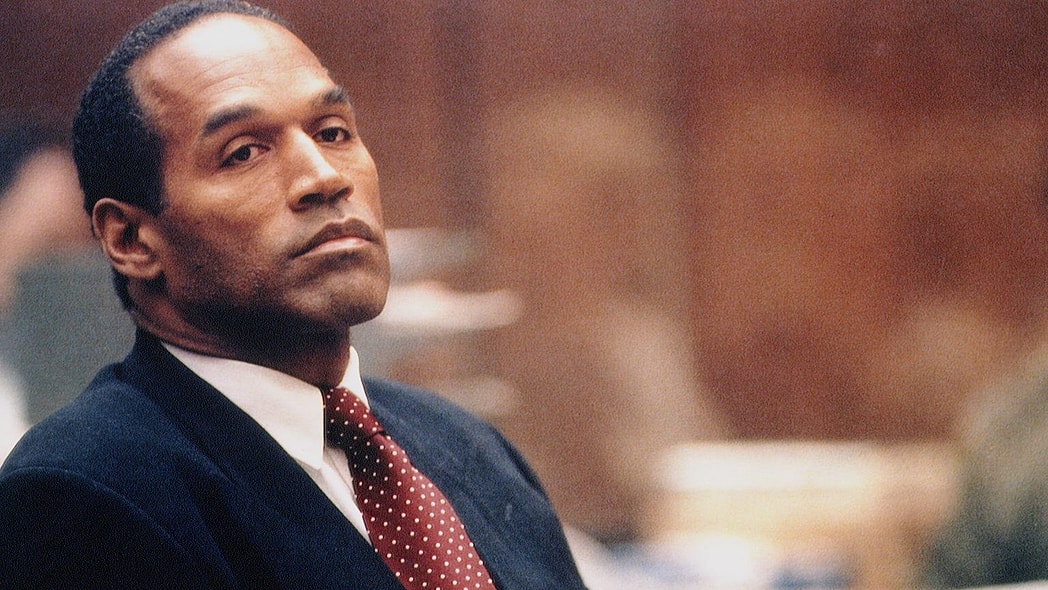

He died Wednesday at age 76, leaving an indelible mark on culture. Though he made his name as a legendary football player. Simpson goes down as sports’ greatest example of “two Americas.”

O.J. ignored racial reality for his first 47 years, running from USC to the NFL, leaping from TV commercials to Hollywood, avoiding our struggle for justice. When he finally came to grips with the color line, it wasn’t first revealed as a black-and-white issue.

His demarcation was on the calendar, a date in June 1994, the day before and after Nicole Brown Simpson’s slaying.

O.J. was among America’s all-time favorite Black athletes until his ex-wife and her friend, Ronald Goldman, were stabbed to death in Los Angeles. He certainly was more affable than the likes of Jim Brown, the great NFL halfback who retired in 1966, three years before Simpson’s rookie season. Brown came across as angry and surly — anathema to white embrace — and further distanced himself by becoming a social activist.

Athletes and celebrities aren’t mandated to use their platform to fight for causes, least of all against racism. Decry domestic violence and sexual assault? Gotcha. Rail against drug use and drunk driving? Sure. Condemn bullying and animal abuse? OK.

But very few stars have what it takes — the will and the skill — to address unjust laws, police brutality, discriminatory policies and the like. Simpson wasn’t alone in that regard. He just went out of his way to not see color, endearing himself to the gaslighters who insisted race wasn’t an issue. From their vantage point, Simpson’s acting career and second marriage were proof of America’s greatness and its absence of animus toward Black people.

Simpson was Black but not in a bad way. He was one of them — like Clarence Thomas, Herschel Walker and Tim Scott — enjoying the fruit of his labor in the land of opportunity, not complaining about barriers and obstacles meant to hinder non-whites. Athletes like Brown, Muhammad Ali, Arthur Ashe and others were malcontents, rabble-rousers, race-baiters; Simpson was a good ol’ boy.

But when he was accused of killing his blonde, blue-eyed ex-wife, all bets were off. White folks were through, leaving him no option: He had to recognize and embrace his Blackness.

News accounts said Simpson’s murder trial exposed divisions on race and policing. That’s laughable in our community because the divisions have been in plain sight for 400 years. The difference in this case was Simpson’s celebrity. A Black Orenthal Smith or James Johnson likely would’ve been convicted under that mountain of evidence — with or without police malfeasance.

If Simpson didn’t think he was Black before the murders, he was certain before the trial began.

“The system has forced me to look at things racially,” he’s heard declaring on the Oscar-winning documentary, “O.J.: Made in America.” One scene in the five-part documentary shows Simpson’s legal team rearranging his house to increase its melanin quotient, the opposite of Black homeowners who remove telltale signs to receive a fair appraisal.

He didn’t fool us but we didn’t care.

After centuries of trumped-up charges and wrongful convictions (when lynchings didn’t occur first), after suffering at the hands of dirty cops, sleazy prosecutors and racist jurors, we wanted a win by any means. No, we didn’t really rock with O.J. like that. But the system had hemmed up so many innocent brothers since 1619, his acquittal became our victory, guilty or not.

Barack Obama reportedly said many Donald Trump supporters can relate: “Trump is for a lot of white people what O.J.’s acquittal was to a lot of Black folks — you know it’s wrong, but it feels good.” We knew the murder victims weren’t responsible for the LAPD’s historic mistreatment of Black folks, but the scoreboard was too lopsided.

For once, our side got a taste of the other side, where guilty parties routinely escape punishment after snuffing out Black lives. Simpson went from being a model Negro to an unrepentant murderer. Along the way, he was jarred from the sunken place and beamed to the real world, exposed to the dual Americas that Martin Luther King Jr. described.

Simpson carried himself like there was only one … until he was charged with murder. Then he acknowledged his mistake and set both sides ablaze, etching his name in hearts and minds. His name stands out in the annals of time.

Haters might be mad, but that Black history can’t be erased.

It’s an L they have to live with.

Deron Snyder, from Brooklyn, is an award-winning columnist who lives near D.C. and pledged Alpha at HU-You Know! He’s reaching high, lying low, moving on, pushing off, keeping up, and throwing down. Got it? Get more at blackdoorventures.com/deron.