Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

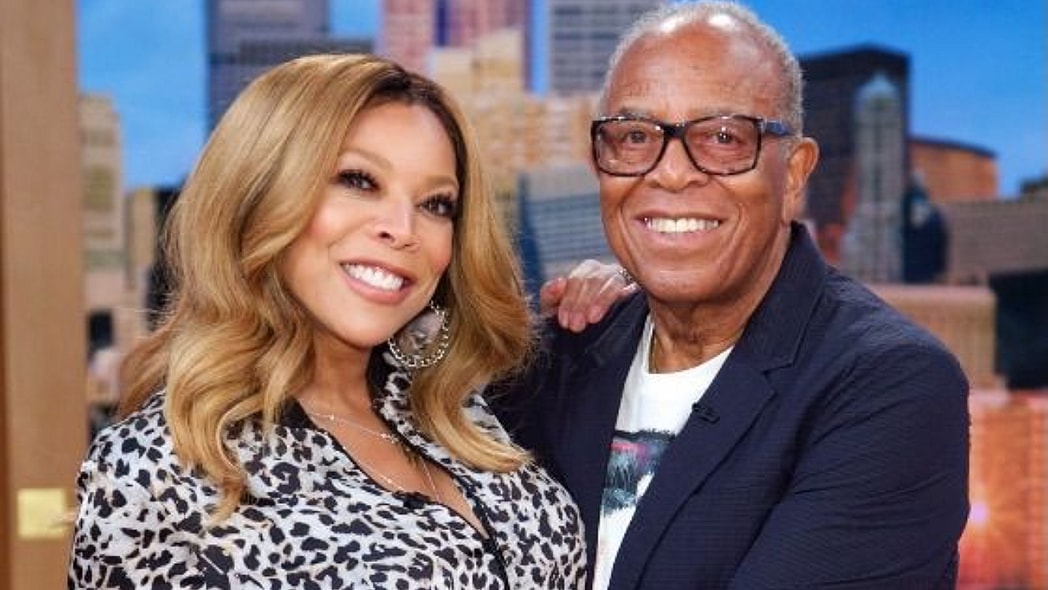

Recent news of Wendy Williams’ diagnosis of aphasia and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), the same condition affecting actor Bruce Willis, is sending shockwaves throughout the Black community.

Williams, 59, most famous for her radio and television hosting career, disclosed the diagnosis on the Lifetime series “Where is Wendy Williams?” a two-part documentary about her physical and mental health.

The former host of “The Wendy Williams Show” has a long history of health problems ranging from cocaine addiction to cocaine Graves’ disease and hyperthyroidism. In 2017, she fainted on set during a live taping on Halloween, and in 2019, she acknowledged living in a sober house, after being found unresponsive in her New York apartment, necessitating an emergency hospitalization and two blood transfusions, a few months prior. But the diagnosis of FTD was a bombshell to many, and a reminder of dementia’s impact on the Black community.

Frontotemporal dementia’s grip on the Black community

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) disproportionately affects the Black community compared to others, and the reasons remain unclear. Although research on FTD in Black populations has grown significantly over the past two decades, the disease’s complex nature makes it challenging to pinpoint a single definitive cause.

Alarmingly, rates of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are on the rise among Black Americans over 70. This is particularly concerning because FTD is both early-onset and rapidly progressive, affecting a significant portion — over a quarter — of this population who are already living with some form of dementia, with Alzheimer’s being the most common. Black Americans are also less likely to receive a timely diagnosis and more likely to see four or more doctors before receiving a diagnosis, according to the Associate for Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD).

Even more, symptoms of FTD tend to be more severe in Black people — according to a 2023 University of Pennsylvania study, Black study participants reported experiencing a higher degree of dementia severity on the Clinical Dementia Rating Dementia Staging survey, compared to white and Latinx individuals.

Frontotemporal dementia uncovered

The exact cause of FTD is unknown, but it involves progressive neuronal damage in the regions of the brain responsible for language production, typically affecting individuals younger than 65. As the disease progresses, the brain shrinks, further impacting areas that control behavior and personality.

Recommended Stories

While symptoms vary from person to person, early signs of FTD (which may appear as early as age 45) may involve speaking less frequently, trouble sleeping, and personality changes, such as a lack of empathy or exhibiting socially inappropriate behavior, such as swearing or stealing. Other symptoms include:

- Impaired judgment

- Apathy

- Decreased self-awareness

- Loss of interest in normal daily activities

- Emotional withdrawal from others

- Loss of energy and motivation

- Language difficulty or delays including trouble naming objects, expressing words, understanding the meanings of words, or hesitation when speaking

- Loss of concentration

- Trouble planning and organizing

- Frequent mood changes

- Agitation

Though the specifics of Williams’ symptoms and her family’s observations are unknown, frontotemporal dementia often presents with subtle signs that are easily missed in the early stages. Further complicating matters, diagnosing FTD is a challenge. It requires a detailed account of symptoms, family history, and medications, along with brain scans and blood tests. Often, FTD is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning it’s reached only after other potential causes have been ruled out.

Frontotemporal dementia currently has no cure. However, supportive care strategies like therapy, behavioral modification and medication can help patients adjust to their new reality and manage the ongoing mental and physical changes associated with the disease. No drug has been found to stop or reverse the progression of frontotemporal dementia, but cholinesterase inhibitors (the drugs used to treat Parkinson’s), antidepressants, and antipsychotic medicines, such as Trazadone, can help reduce symptoms of agitation, aggression, and insomnia for some people.

Living with frontotemporal dementia

Wendy Williams’ recent diagnosis has understandably led to speculation about a connection to her past struggles with substance abuse. However, there is currently no evidence to suggest a link between the two.

Experts acknowledge the significant challenges faced by individuals in the early stages of FTD, including fear, frustration, and even embarrassment. One of the most concerning aspects of FTD is the progressive loss of independence. While the specifics of Williams’ situation are unknown, the disease often necessitates a significant level of care, requiring a combination of medication, in-home care, potential nursing home placement, and various therapies like speech and mental health support, which may place a substantial financial burden on her family.

Advanced planning, eases that burden and helps facilitate smooth future transitions for the patient and their family.

The need for more research

The path to unraveling the complexities of FTD may lie in earlier diagnoses and enhanced research efforts, with a particular focus on increasing participation within the Black community. While increased participation from Black communities is crucial for advancing FTD research and developing better treatments, a collective effort is necessary to ensure equitable access to research opportunities and healthcare resources.

Dr. Shamard Charles is the executive director of graduate studies in public health at St. Francis College and sits on the Medical Advisory Board of Verywell Health (Dot Dash-Meredith). He is also host of the health podcast, The Revolutions Within Us. He received his medical degree from the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and his Masters of Public Health from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Previously, he spent three years as a senior health journalist for NBC News and served as a Global Press Fellow for the United Nations Foundation. You can follow him on Instagram @askdrcharles or Twitter @DrCharles_NBC.

Never miss a beat: Get our daily stories straight to your inbox with theGrio’s newsletter.